Homeless shelters are nowadays widespread social features, and many non-governmental organizations and government programs worldwide try to make life easier for the poor and the needy. These programs don’t always work as they should, but some socially conscious initiatives truly make the world a better place.

Historically, homelessness has been a persistent problem that went hand-in-hand with poverty, destitution, and economic crises. It is likely that most nations that have ever existed have experienced socioeconomic inequality in which the poor needed to be helped by those in power or those eager to better the world.

In England, the problem of homelessness and poverty was mostly ignored by the general public until the second half of the 19th century when a branch of the Christian Protestant church founded the Salvation Army, an organization that set out to take care of the poor and the hungry. Over the years, the organization spread throughout the world, but its efforts began in London in 1865.

One of the first efforts of the Salvation Army was the so-called “four penny coffin”, also known as the “coffin house”. The four penny coffin was one of the first homeless shelters created for the people of London in Victorian England.

The shelter was named the “four penny coffin” because its sleeping quarters consisted of rows of coffin-shaped beds where homeless people could spend the night for a sum of four pennies. The four penny coffin was popular because it was cheaper than several small shelters that existed at the time, and its clients praised it because the Salvation Army allowed them to actually lie down and sleep on their backs.

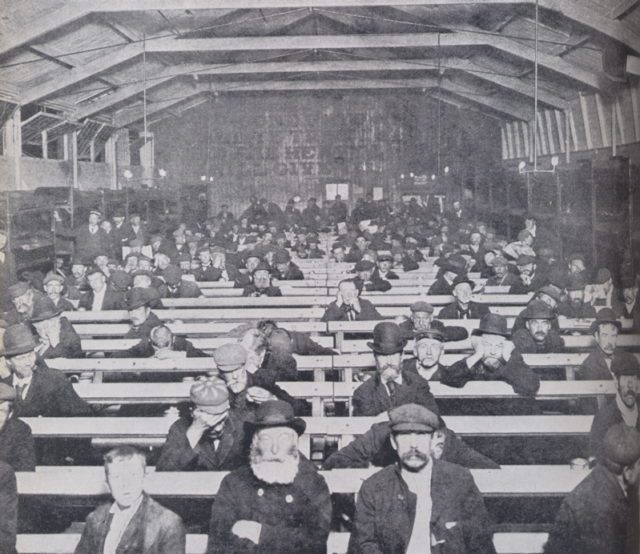

Other shelters enforced a practice that seems somewhat cruel: the homeless people would pay to spend the night, but they were only allowed to sit on benches while resting. The four penny coffin practiced the same rule, but only for those who couldn’t afford a coffin-bed for four pennies.

Those who could only come up with a single penny were allowed to sit on the shelter’s benches and rest, but they weren’t allowed to sleep and the shelter’s officials monitored the rooms at night to shake any poor folks who closed their eyes and drifted into a troubled slumber.

However, those who managed to pay the price of two pennies were able to afford the so-called “two penny hangover”: they couldn’t enter the sleeping quarters but were allowed to sleep on the shelter’s benches.

A piece of rope was tied to each bench and the clients could lean on the rope to achieve a more comfortable position. The pieces of rope were cut early in the morning so that the shelter’s clients would wake up early and leave the premises.

This practice continued in the first half of the 19th century but died out when government programs started providing beds for the homeless free of charge.

Nowadays, spending the night at a homeless shelter is usually free, since the purpose of homeless shelters is to provide relief for the poor without forcing them to spend additional money on accommodation.