Under normal circumstances, FBI forensic scientists would not work on analyses of ancient Egyptian mummies, but this is what happened in the case of the mummified remains of a certain ancient Egyptian governor whose name goes as Djehutynakht … who was beheaded.

The mummy was found in 1915, but the tomb was in a fearful condition. Laid to rest some four millennia ago, the body had been removed from its tomb and was dumped in a corner of the chamber–with its detached head sitting atop one of the coffins.

Since the discovery of the site, it has been a mystery: to whom did the decapitated remains belong? This and several other questions would still be left unanswered if it weren’t for the help of FBI scientist Dr. Odile Loreille and her team. According to the New York Times, Dr. Loreille joined the agency after two decades’ experience in studying ancient DNA.

The entire story of this strange, decapitated mummy and its puzzling identity begins in 1915, when a team of U.S. archaeologists exploring the site of Deir el-Bersha, an ancient necropolis in Egypt, stumbled upon one abandoned tomb. Inside the chamber, the scene was unlike anything they could have expected. The mummy was found severed in two, and it was more than obvious the chamber was also a crime scene. That at some point in its long past, its treasures had been looted.

The tomb had been emptied of any fine jewels that it likely held, as such goods for the afterlife would certainly have been left for the deceased. As the New York Times writes, whoever the grave robbers were, they also tried to conceal their traces and attempted to set fire to the room.

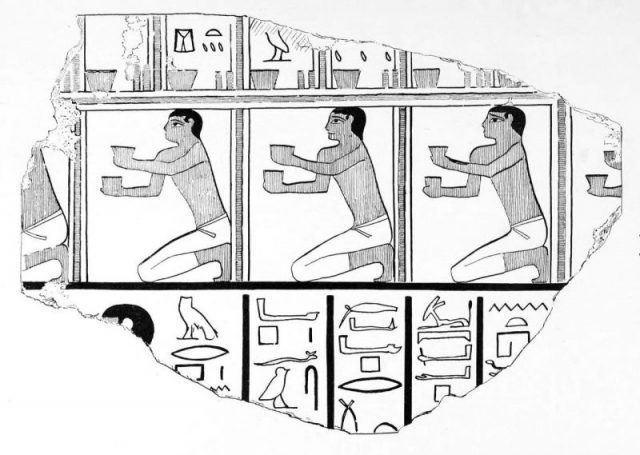

Still, it was established that the chamber was used to bury a governor named Djehutynakht who administered a province in Upper Egypt. Since the site was around four millennia old, this would have happened during the days of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom. And as the governor’s tomb was laid next to that of his spouse, a part of the mystery has been whether the decapitated mummy belonged to the governor himself or his wife. The high status of Djehutynakht is clear, given the lavish decoration as seen on their coffins.

The findings from the most recent analysis of the remains have been published in the journal Genes on March 1, 2018, when experts confirmed the remains belonged to a male, hence the mummy was most likely the governor himself. The paper also explains the exact methods used by experts to recover the exceptionally old DNA material.

The burial chamber was named Tomb 10A by the archaeologists who found it, and much of its contents were carried to the United States by the early 1920s. The torso remained in Egypt, but other artifacts, including the most valuable one, the head, arrived in Boston. They were stored at the city’s Museum of Fine Arts. The artifacts also included the lavishly decorated coffins as well as funerary figurines that survived the grave-robbers. Most of the assembled artifacts reportedly remained in storage until the museum proceeded to exhibit them in late 2009.

Since it was still an open question, interest in investigating the identity of the mummy was re-ignited by the exhibition. Were novel scientific methods and new technologies capable of closing a century-old debate? It wasn’t easy, especially in the beginning, when multiple analyses failed to bear any fruit.

Scientists and experts opted for DNA analysis because of the condition of the mummy’s head. From CT scans, the team found out it was mutilated, with missing bones from the jaw as well as the cheek. These bones had reportedly been cut out when the deceased body was being mummified and prepared for the afterlife. Had those bones been saved, experts could have had a clue of the mummy’s sex much earlier.

According to the New York Times, various parties, including doctors, are astonished by the manner in which the missing bones had been removed from the head. Experts even repeated the surgical procedure on cadavers, imitating the ancient Egyptians to see if they were really able to cut out the specific facial bones with such precision using the limited surgical tools they would have had at their disposal. It turned out, they could perfectly do that.

But in the end, the answers hung on the results of DNA analysis. Against all odds, the results came in, regardless of the fact that securing DNA samples from mummies of ancient Egypt was something never achieved before, as the environment in which the mummies are laid to rest is unfavorable for DNA preservation.

As earlier attempts for a successful DNA extraction had failed, in 2016 the case was passed to FBI forensic experts. The New York Times reports that Dr. Loreille used a tiny piece of a well-preserved molar tooth that was taken out of the mummy’s head in 2009. The minuscule sample of tooth was ground into a fine powder, then treated with a substance that allowed Dr. Loreille and her team to see an amplified amount of the DNA it held.

In the process, the experts were able to confirm they are looking at ancient samples of genetic material. With advanced software to map the DNA sequence, soon the results revealed that the head belonged to a male.

According to Live Science, however, one question is still unanswered. Supposedly, there had been two governors who bore the name Djehutynakht and administrated the same Egyptian province.

Nevertheless, the entire effort is significant for several reasons, including that this was one proof that DNA can be harvested from ancient Egyptian mummies. Furthermore, the examinations shed light on other intriguing questions, such as the ancestry of the ancient Egyptians. Were these people close relatives to the modern-day people who inhabit the North African region? Surprisingly, the DNA of Djehutynakht hints he had a Eurasian lineage, at least from his mother’s side. But as experts remind us, serious conclusions on these matters will require further research.