It was three o’clock on a cold spring night in 1777 and except for the light drumming of rain on the rooftops, the only sound heard on the deserted streets of New Haven, Connecticut, was the clopping of horse hooves as a messenger made his way to his destination, a white clapboard residence on Walter Street.

He knocked on the door, and, once the master of the house was roused, the messenger delivered his urgent news: Just yesterday, April 25th, the British had invaded Connecticut, landing 2,000 troops at Compo Point near Norwalk, where the Saugutuck River opens into Long Island Sound. Connecticut had seen no battles yet in the war, but that seemed about to change: at this very moment, the enemy was bivouacked just seven miles from the coast.

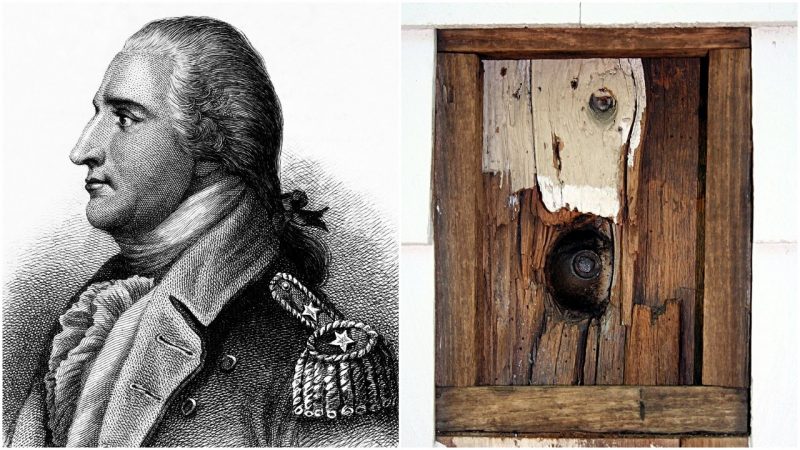

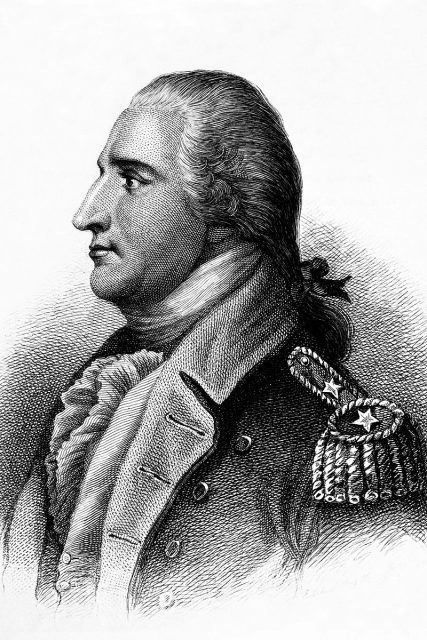

Benedict Arnold took the news calmly. He slipped on his uniform: buff pants, high black boots, a shirt with a pink ribbon sash, and a blue coat with red trim. He buckled his sword. His foot was swollen from gout, but he limped to the stables, mounted his horse, and hurried off to battle.

It was only four months earlier that the American commander in chief, George Washington, had enervated the patriot cause with victories at Trenton and Princeton, but now, during that optimistic spring of 1777, Benedict Arnold languished in his New Haven home, depressed and resentful, not officially on leave from the army, but inactive and on the verge of resigning, bitter over a year of betrayals and scandals and affronts to his pride which he found impossible to tolerate. It was three years before his treason, an act that would make his name a byword for betrayal to this day.

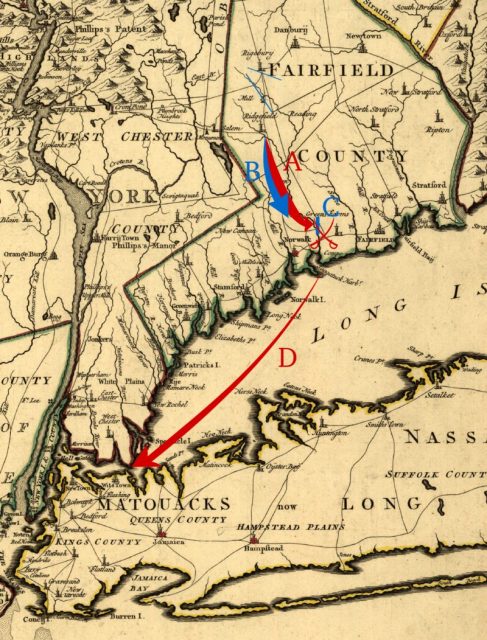

A: British movement to the coast

B: American movements to pursue and harass the British

C: Arnold’s position attempting to block the British return to the beach

D: British return to New York

Arnold hadn’t been in a fight for six months, since the Battle of Valcour Bay in October 1776, when his hastily constructed fleet, outnumbered and outgunned on the turbulent waters of Lake Champlain, had held back the British fleet under Sir Guy Carleton, delaying the British invasion from Canada for another year and providing the patriot cause with a needed respite.

After Valcour Bay, Arnold waited confidently for promotion from brigadier to major general, an advancement he felt was well deserved. Arnold was obsessed with position and honor, tormented perhaps by the childhood shame of seeing his father, a respected Connecticut merchant, grandson of a Rhode Island governor, sink deep into alcoholism and debt, hitting bottom with the ultimate disgrace for this Puritan family: his arrest for public drunkenness. The same year, the family home was sold to pay the father’s debts. Benedict was 19.

In February 1777, Congress elevated five brigadier generals over Arnold’s head, a move that reflected a political struggle in Philadelphia between Washington’s allies and others, such as John Adams, who feared the growing popularity and power of the military authority over the civilian. On the same day the promotions were announced, Congress also passed the Baltimore Resolution, a success for the radicals in Congress who supported the power of the states over a federal government. The Resolution provided that Congress, in appointing new generals, would take into account not only merit but the “quota of troops raised, and to be raised, by each state.”

A frustrated Arnold, unable to see that he was only a pawn in the murky stratagems of revolutionary politics, took the slight personally. He felt helpless, sensing that his life and career were subject to irrational and corrupt manipulation beyond his control.

Also hanging over his head were accusations of plundering, not-quite-formal charges of looting the property of private citizens during the American retreat from Montreal the year before. He repeatedly demanded a court of inquiry to clear his name. Arnold had largely financed the Quebec expedition from his own pocket and had not been reimbursed.

But on the morning of April 26th, he later wrote he was heartened at the prospect of battle, for the battlefield was a place free of politicians and he could make decisions governing his own fate. He and David Wooster, the Major General of the Connecticut militia, rode together to Fairfield. They would find about 500 farmers, tradesmen, blacksmiths, and other members of the militia waiting for them.

The British invasion force, a flotilla of 12 transports and 1,850 men, had set out from New York City on April 22, 1777, and sailed up the East River into Long Island Sound escorted by the sloops Senegal and Swan. Advance troops reached Compo Point on Sandy Beach and secured two hills about one and a half mile from the beach head. The British had brought some of the most experienced troops of the continent to take their objective: the well-stocked patriot storage depot in the southwestern Connecticut town of Danbury.

British strategy called for the isolation of New England, a move that it hoped would remove this rebellious center from the war entirely. Once everyone was ashore for the Danbury objective, the British troops marched inland up the Danbury Road, dodging fire from locals. Once the news spread of their presence, George Washington, among others, assumed their real destination was somewhere on the Hudson, such as Peekskill, not Danbury. Making things worse, Washington had already removed most of the Continentals from Connecticut.

When the British pulled into Danbury unopposed, they spent almost two days eliminating supplies for the Patriot rebels. The expedition was led by the Royal Governor of New York, William Tryon, a 48-year-old aristocrat considered “vain to an extreme degree” with wealth and connections who had served in the army for 20 years.

Arnold and Wooster, aware of the destruction at Danbury, decided to divide their forces. Arnold would try to block the British advance. When he received word that Tryon’s men had turned south and were headed for the village of Ridgefield, he force-marched his men through the New England countryside, across the damp fields and roads, past tidy houses with shuttered windows.

Benedict Arnold and his men made it to Ridgefield at 11 A.M., just a couple of hours ahead of the British. He decided to make a stand on Main Street, the empty dirt road running through the tiny village. He set his men to construct a barricade, while he remained on his horse to direct them. They used logs, wagons, chairs, and soil to do so.

At 2 P.M., Governor Tryon appeared before them with his men. Some of his junior officers had fought in the War of the Austrian Succession. The redcoats advanced on Arnold’s line in a single column, the officers first, with swords drawn, then three field pieces in front, three in the rear, and a large flank of guards. Tryon sent detachments to outflank the barricade and wheeled forward his cannon, sending grapeshot and metal hurling at the upturned wagons and dirt. When the cannon fire ended, the infantry discharged their muskets.

Arnold ordered his men to fire back, and there ensued what Benedict later described as “a smart action which lasted for about one hour.”

It wasn’t long before the barricade was overwhelmed. Most of the militia fled while Arnold remained on his horse, trying to organize an orderly retreat. Some grenadiers emerged on the American left and as Arnold wheeled to fire, nine bullets flew into his mount, knocking the horse down and pinning Arnold face-down in the mud. As he struggled to get his boots free of the stirrups, a New England Tory advanced with a bayonet shouting, “Surrender! You are my prisoner.”

Arnold freed himself, lunged for his pistol, and shot the Tory dead while uttering the words: “Not yet.” Arnold then managed to run into the forest.

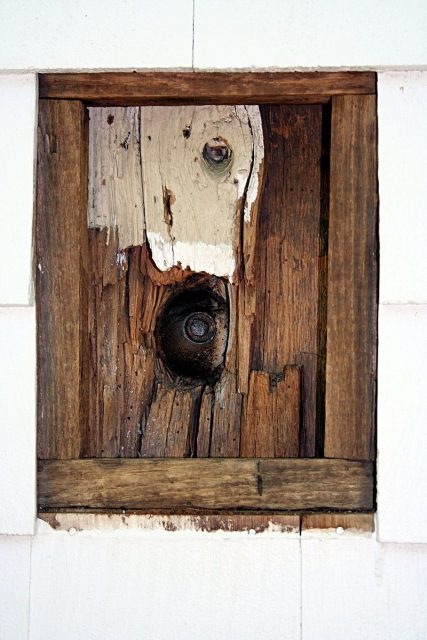

The British cannons dispatched more fire into the town. One cannonball blasted its way to the north wall of Ridgefield’s tavern, where it can still be seen today. The British burned six houses and two barns before they left.

Meanwhile, Arnold collected militia, and headed for the mouth of the Saugatuck River, determined to block Tryon again, using his knowledge of the Connecticut countryside to maneuver. Arnold set up his men to block a bridge, near what is now Westport, that Tryon’s soldiers would need to use to get to their waiting ships. When the British arrived at the bridge and saw the rebels, they swung to a shallow part of the river to cross. Arnold urged his militia to pursue and attack but many would not budge.

Arnold, oblivious to a bullet that had already torn through the collar of his coat, rode up and down the field, urging his men to pursue the enemy. His cries were only halted when a second horse was shot from under him. His men were advancing, though, and the British, exhausted and harried, were running out of ammunition. They charged with fixed bayonets, which panicked the New Englanders, and, their nerves “unstrung,” some of them fled. Others fought.

The battle, lasting about three hours, ended, and the British made it to their ships. The casualty figures were 60 Americans killed or wounded with 120 British casualties and 20 taken prisoner. While the British did achieve their tactical objective, they would never again attempt to sail to a place and then march inland to attack a rebel stronghold.

Benedict Arnold’s bravery was widely acclaimed by the entire nation. His ensuing promotion did not carry all the seniority he felt he deserved, however, and he fumed. In six months, he distinguished himself again at the Battle of Saratoga. But that would be his last action as a patriot. When he served as military governor of Philadelphia, it provided fertile soil for his bitterness and indignation, emotions that would so envelop him that Benedict Arnold would betray those who he was convinced had in a dozen ways already betrayed him.

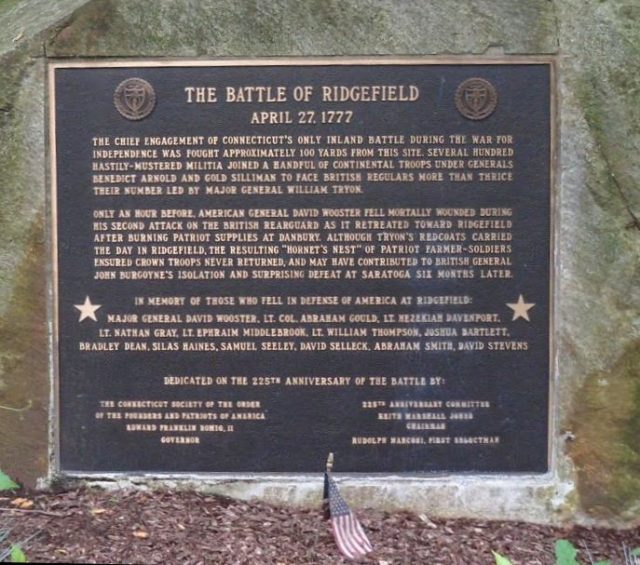

The Battle of Ridgefield was the only inland battle fought in the state of Connecticut during the Revolutionary War. Keeler Tavern Museum staff proudly show the British cannonball lodged in a corner post to visitors today.

Max Eastern is the author of the noir thriller “The Gods Who Walk Among Us,” a winner of the Kindle Scout competition. To learn more, go to maxeastern.wordpress.com