They say, “You can’t keep a good man down,” but what about women? Here, some truly bizarre, old-timey medical “conditions” created to keep females from getting too independent:

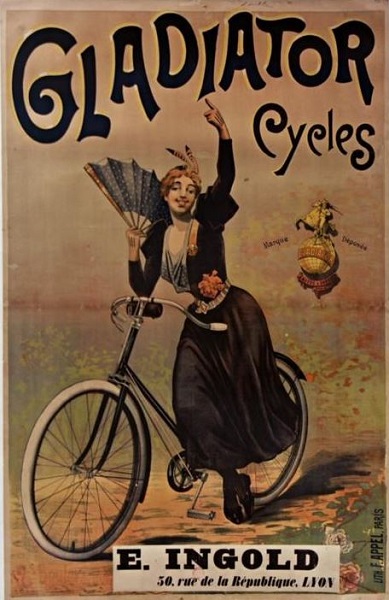

Bicycle Face: Bicycles became a big deal for women in the late 1800s, both in the U.S. and in Europe. Not only were they fun ways to tool around town and a way for women to travel without a man.

They were also a symbol of feminism, taken up by women in the suffragist movement.

Besides giving women a kind of independence, the two-wheelers helped loosen up the dress codes. (Women needed to wear less binding clothes to partake in this activity, so body-hugging corsets were cast aside.)

As Munsey’s Magazine put it in 1896: “To men, the bicycle, in the beginning, was merely a new toy, another machine added to the long list of devices they knew in their work and play. To women, it was a steed upon which they rode into a new world.”

Which, naturally, rattled a lot of men. To scare women, physicians came up with a laundry list of health problems women could expect to experience while pedaling away: headaches, depression, exhaustion, insomnia, and heart palpitations, among them.

But the real doozy was something called “bicycle face.” In short, they warned women that the “awkward and ugly” faces they made while exerting themselves just might stay that way.

The Literary Digest, in 1895, described the condition as “usually flushed, but sometimes pale, often with lips more or less drawn, and the beginning of dark shadows under the eyes, and always with an expression of weariness.”

Others claimed the affliction was “characterized by a hard, clenched jaw and bulging eyes.” This gave ammo to the menfolk, who argued that cycling was most unsuitable for women. Still, women rode on—facing numerous obstacles in their path. (Among the rules implemented in New York: “Don’t refuse assistance up a hill.”)

Finally, nearing the close of the 1900s, common sense prevailed, with many physicians questioning the existence of bicycle face, saying that when people—men or women—concentrate when operating any vehicle, be it a bicycle or automobile, their facial expressions often change, without permanent damage.

Chicago doctor Sarah Hackett Stevenson offered her two cents in an 1897 issue of the Phrenological Journal: “[Cycling] is not injurious to any part of the anatomy, as it improves the general health. I have been conscientiously recommending bicycling for the last five years.”

“The painfully anxious facial expression is seen only among beginners and is due to the uncertainty of amateurs. As soon as a rider becomes proficient, can gauge her muscular strength, and acquires perfect confidence in her ability to balance herself and in her power of locomotion, this look passes away.”

Victorian words we should be using today

Hysteria: Literally translating to “womb disease,” this ailment prompted a list of down-below symptoms including anxiety, sleeplessness, irritability, sensations of heaviness in the abdomen, and vaginal lubrication—for starters.

It was treated by doctors or midwives, who massaged the genitals to the point of orgasm.

Today, it would most likely be diagnosed as a prolapsed uterus or an ovarian problem. (Fun factoid: This “affliction” made vibrators fairly commonplace in doctors’ offices at the close of the 19th century.)

The Vapors: It sounds like something Scarlet O’Hara would be moaning about while fanning herself after a plantation shin-dig, right? But the term, which entered the vernacular during the Victorian Era and stuck around right into the 1920s, was used to describe pretty much anything from a bad case of PMS to hypochondria, and even something as serious as clinical depression.

However, it was most likely a way of describing what we today would consider anxiety. Back in the day, women were regarded as fragile little things. The origin of the word vapors actually refers to ammonia vapors, such as the kind wafting from smelling salts, which were often employed to bring these lightheaded gals back to life.

Eventually, the phrase “I’ve got the vapors” was something of an umbrella term that could mean a host of “female” ailments, like dizziness, bloating, and depression—all of which, back then, could be remedied by a quick sniff of smelling salts.

Wandering Womb: Gotta love the ancient Greeks. They were masters of science, astronomy, and literature. But when it come to women stuff—not so much. Case in point: the traveling uterus.

The Greeks—Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, included—believed in “an animal within an animal” that rattled around a woman’s lower regions, effecting her moods and health. The prescription for this volatile creature: pregnancy. And the more bouts of childbirth, the better, since physicians believed the “animal” (in our world, the womb) was moving around out of boredom.

One Byzantine physician suggested yelling at women (or making them sneeze) to keep the womb quiet. The brain trusts of the 17th century believed a wandering womb could be quieted with pleasant scents applied directly on a woman’s genitals.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.