Nearly every American of a certain age grew up with the story of Pocahontas: How the young Native American, the daughter of Chief Powhatan, put her own life at risk to rescue the captured Captain John Smith from certain execution, turning her back on her own people to save an Englishman.

Those who know the story from Disney’s fictionalized 1995 animated musical may even still believe the romanticized idea that Pocahontas fell madly in love with Captain Smith.

Too bad it’s not exactly true. Like many legends passed down through generations, the Pocahontas story started with seeds of fact but morphed over the years to suit the needs of the tellers and the times.

For starters, Pocahontas wasn’t even her real name, according to a biography published on the National Park Service’s Historic Jamestowne site. Her name was Amonute; she also had a more private name of Matoaka, or “flower between two streams.”

Pocahontas, which means “playful” or “ill-behaved,” was a nickname. She was born around 1596, a member of the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia, the favored daughter of Chief Powhatan, the ruler of 30 tribes around the area that the English would call Jamestown, Virginia.

Pocahontas was probably between 9 and 11 years old when Captain Smith, who’d arrived on the coast of what is now called Virginia in 1607, was captured and held for some months.

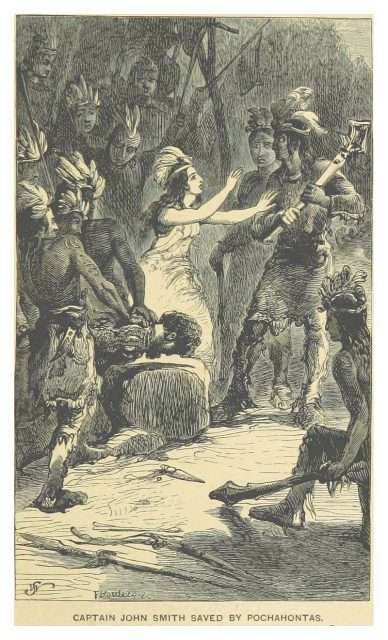

According to the story that John Smith wrote and promoted, he was brought in front of Chief Powhatan to be executed (so he thought), his head placed between two stones, when Pocahontas rushed in to save him by placing her own head atop his.

Historical research has cast doubt on this version, but regardless, Captain Smith was released and he returned to Jamestown. Native Americans sent food to the starving settlers; some believe Pocahontas accompanied the party that delivered the provisions.

Smith’s version is refuted in The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History, published in 2007 by Dr. Linwood “Little Bear” Custalow and Angela L. Daniel “Silver Star” and based on oral history of the Mattaponi tribe.

In this more modern version, Chief Powhatan genuinely liked Captain Smith and the ritual with stones was meant as a ceremony. Pocahontas would not have been present, even though she was a favored daughter, as she was too young.

According to Custalow and Daniel, Smith didn’t meet Pocahontas until she came with her people to deliver food to Jamestown. While she may have made the journey to Jamestown with members of the tribe, it was a difficult trip and as a young child she certainly would never have made it on her own, as enduring myths suggest.

Within two years, relationships between Native Americans and the English explorers deteriorated. The starving settlers needed more food; the Native Americans couldn’t provide it.

Another legend has it that Pocahontas ran through the woods alone to warn John Smith that his life was in danger, saving him once again. Smith claimed Pocahontas twice saved his life in his 1624 book General Historie of Virginia, long after many of the main players had passed away.

Around 1610, Pocahontas, then around 14 years old, married Kocoum, possibly of the Patawomeck tribe, whom the two would live among for a short time. The two had a child, according to some sources.

What is certain is that in 1613, Captain Samuel Argall kidnapped Pocahontas for ransom; Kocoum was killed. While held in captivity, she suffered from depression and was most likely abused. She learned the English language, customs, and religion.

In 1614, Pocahontas converted to Christianity, her name was changed to Rebecca, and she was wed to tobacco farmer John Rolfe.

At some point, Pocahontas had a son, Thomas, though whether he was John Rolfe’s offspring or some unnamed assailant is a matter of historical debate. Marrying Pocahontas allowed the tobacco farmer to learn curing techniques from tribal leaders, which turned his venture into a profitable enterprise.

The family traveled to London in 1616, along with Argall, Pocahontas’s kidnapper, and her sister, Mattachanna, who would later write about their adventures.

The True Story of Pocahontas

Pocahontas, now Rebecca Rolfe, was presented to English society to demonstrate that the “savages” could be “civilized”; she may have even met King James I and Queen Anne. Eventually, the Rolfes settled in rural Brentford.

Pocahontas and Captain John Smith had one more meeting. Smith wrote that Pocahontas—who’d been told he had died—was overcome with emotion. Their meeting wasn’t salubrious; they disagreed over what to call each other, according to Smith. It was the last time they’d ever see each other.

The Rolfe family decided to return to Virginia in 1617, but Pocahontas didn’t survive the journey home. So ill she had to disembark before the Atlantic crossing, she died onshore—some say of pneumonia or dysentery; others suggest she was poisoned.

Regardless, she was buried at St. George’s Church in Kent, England. She was around 21 years old. Descendants of Pocahontas and her father include several famous people, including former first lady Edith Wilson and the singer Wayne Newton.

So why did the myth of Pocahontas saving—and even falling in love with—Captain John Smith endure for so many years?

Because it was a story many (white) Americans wanted to believe, as Camilla Townsend, author of Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma and a history professor at Rutgers University, explained to Smithsonian. The Smithsonian Channel produced a 2017 documentary called Pocahontas: Beyond the Myth, which features Townsend’s commentary.

“The idea is that this is a ‘good Indian,’ ” Townsend said. “She admires the white man, admires Christianity, admires the culture, wants to have peace with these people, is willing to live with these people rather than her own people, marry him rather than one of her own. That whole idea makes people in white American culture feel good about our history. That we were not doing anything wrong to the Indians but really were helping them and the ‘good’ ones appreciated it.”

What exactly happened more than 400 years ago is lost to time, but the story of Pocahontas continues to provide fascinating commentary on relationships—then and now.

E.L. Hamilton has written about pop culture for a variety of magazines and newspapers, including Rolling Stone, Seventeen, Cosmopolitan, the New York Post and the New York Daily News. She lives in central New Jersey, just west of New York City