Archaeology in Mexico City has a reputation more exciting than most.

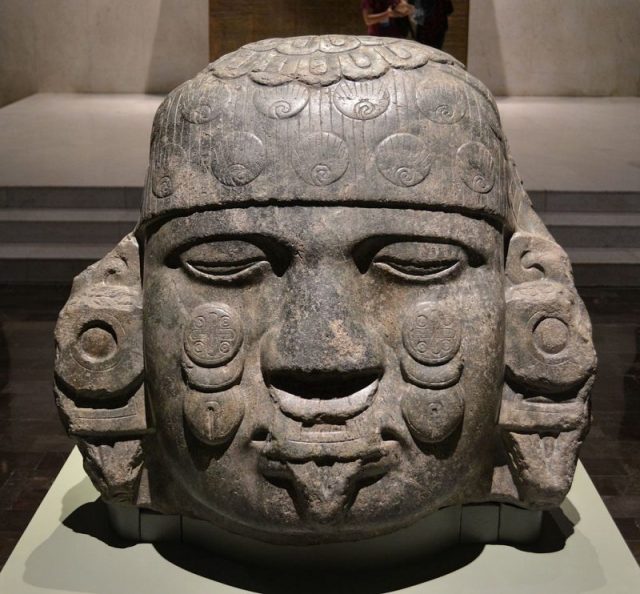

For starters, one of its key finds was made not by archaeologists but electricians. Take what happened in 1978. When a basement floor fell in, a group of workers saw a statue that turned out to be the Aztec goddess Coyolxauhqui.

This discovery heralded the reappearance of the ancient pyramid of Templo Mayor, or rather the foundations of it.

An important part of the island capital Tenochtitlan and home to the Mexica people, it was attacked by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. They built in its place what eventually became the Mexico City we know today.

Tenochtitlan was a city of pyramids, with Templo Mayor acting as a focal point for worship. On top of it were two temples devoted to Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and Tlaloc, god of rain.

The dramatic uncovering of Coyolxauhqui demonstrated there was life in the Mesoamerican culture yet.

Tenochtitlan had been founded in 1325 and its pyramids and temples were the stuff of legend. Not least because of the gruesome stories of human sacrifice that are associated with the society.

The tradition began by cutting out the heart of the unfortunate (or fortunate if you were a believer) soul.

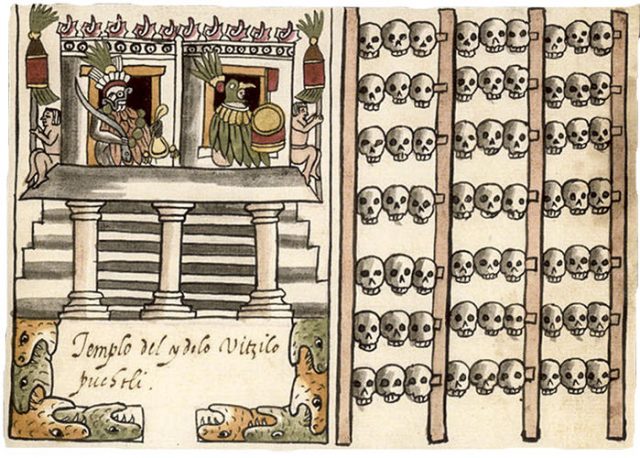

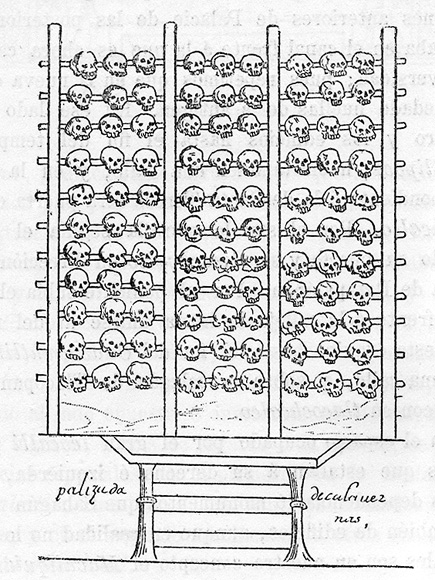

They were then decapitated and the flesh carved from their skull. This then had two holes made at either side before being stuck on a horizontal pole.

According to the conquistadors, they saw evidence of approximately 100,000 skulls around Templo Mayor, formed into a rack of these poles called a “tzompantli.”

In a more modern description, a 2018 article on the website of Science magazine put it like this: “The scale of the rack and tower suggests they held thousands of skulls, testimony to an industry of human sacrifice unlike any other in the world.”

It was never clear whether this vivid description was historical fact or the hyperbole of the Spanish, who wanted to paint the conquered people in as negative a light as possible.

7 Things you may not know about The Mayans.

However, as the previous quote suggests, archaeologists have begun to dig up the tzompantli and look into the hollow sockets of its sacrificial victims.

Beginning in 2015, a team from INAH (the National Institute of Anthropology and History) have been excavating the area by Mexico City Cathedral, where the secrets of Templo Mayor and its skulls are being examined to determine what type of people were sacrificed.

By doing this, they also hope to obtain more information about the role sacrifice played in the day to day existence of the Mexica people. John Verano, a bio-archaeologist, remarked on the combination of religious reverence and political consolidation he believes the sacrifices represent:

“The killing of captives, even in a ritual context, is a strong political statement,” Verano says. “It’s a way to demonstrate power and political influence—and, some people have said, it’s a way to control your own population.”

As for that population, various theories have been suggested as to who was selected to give up their life and appease the gods.

Analysis of isotopes in the skulls’ teeth and bones indicates that victims were resident in Tenochtitlan for a lengthy period of time before their demise.

This backs up the idea that captives lived with local families in the run-up to slaughter, with other experts thinking people were sold specifically for the purpose of sacrifice. Among the skulls are men, women and children, but predominantly men.

Grisly though it is, the collection of skulls being pored over by archaeologists is a historical record of ancient culture. They’re disturbing the sleep of the dead, yet in doing so they are giving them a new lease of life, and us an insight into the world of the Aztecs.

Steve Palace is a writer, journalist and comedian from the UK. Sites he contributes to include The Vintage News, Art Knews Magazine and The Hollywood News. His short fiction has been published as part of the Iris Wildthyme range from Obverse Books