“To regret one’s own experiences is to arrest one’s own development,” wrote the fine master of the written word in his profound 55,000-word love letter composed for Lord Alfred Douglas from inside his cell at the notorious Reading Gaol in Berkshire, England.

“To deny one’s own experiences is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life” was his own belief, even though what he was experiencing at the time was a cruel and unjust two-year sentence of “hard labor, hardboard, and hard fare.” He could easily have fled to France to escape conviction. But he didn’t. He stayed right where he was to be accused of his crime, for as he once approvingly quoted his friend Wilfred Scawen Blunt, “an unjust imprisonment for a noble cause strengthens as well as deepens the nature.”

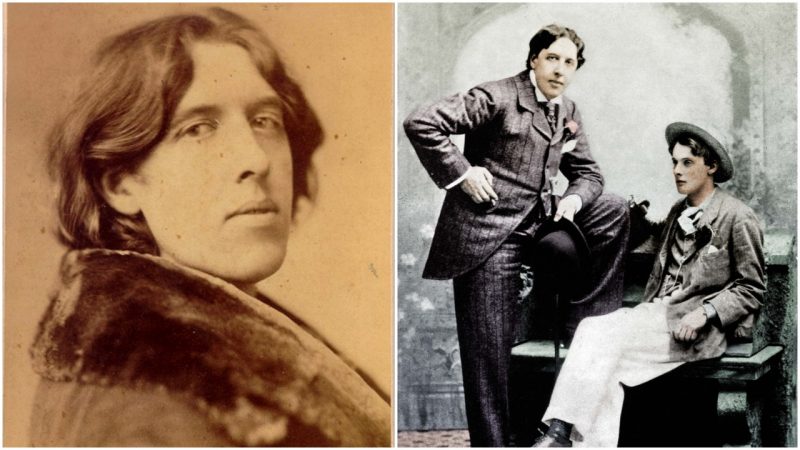

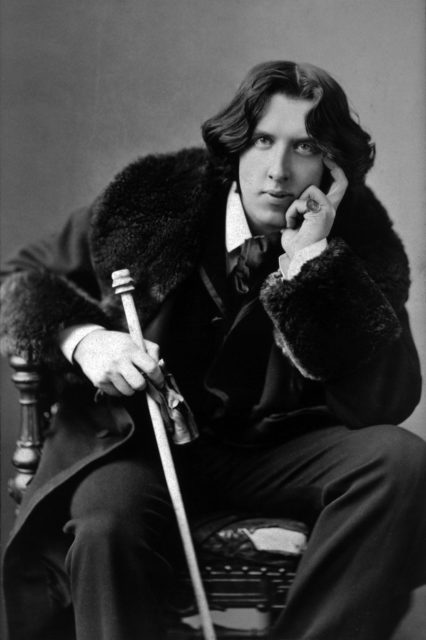

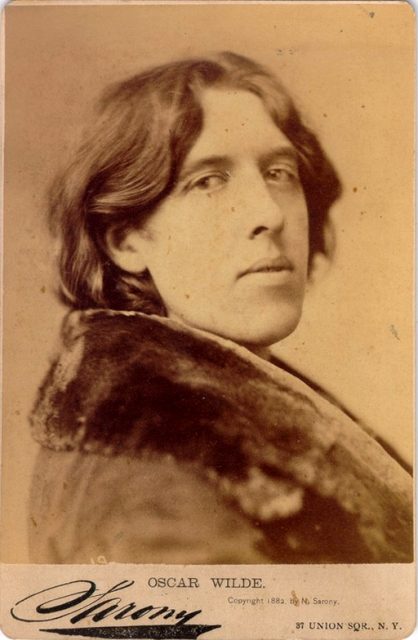

On May 25, 1895, the trial of the flamboyant Dublin born author, poet, and playwright at London’s Old Bailey courthouse concluded with his conviction for the crime of sodomy and gross indecency.

Homosexuality was a serious criminal offense and a social taboo in Britain in the 19th century and Wilde, who was suspected to have enjoyed the “best of both worlds” when it comes to sexual orientation, was held accountable under the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, specifically the Labouchere Amendment that outlawed any intimacy between men, labeling such interactions as “gross indecencies.”

“Any male person who, in public or private, commits, or is a party to the commission of, or procures, or attempts to procure the commission by any male person of, any act of gross indecency, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and being convicted thereof, shall be liable at the discretion of the Court to be imprisoned for any term not exceeding two years, with or without hard labour.”

By banning “gross indecency” in general rather than specific acts of conduct, the amendment made even the most innocent, private and consensual action potentially liable for criminal prosecution, stipulates Nicholas Frankel in his book Oscar Wilde: The Unrepentant Years.

As if it was solely intended to suppress the homosexual subculture that was ever growing in London’s West End, especially among the artistic elite.

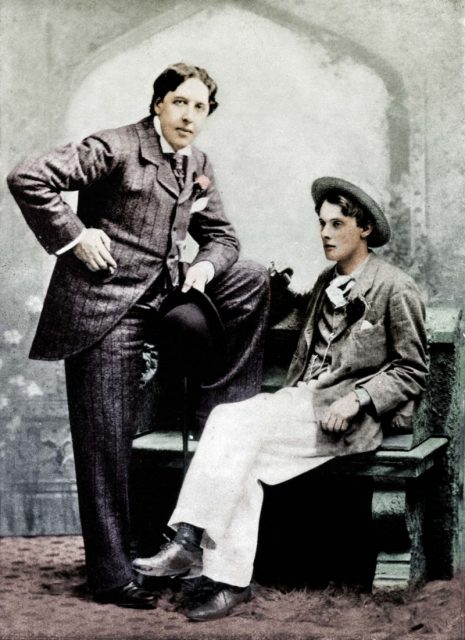

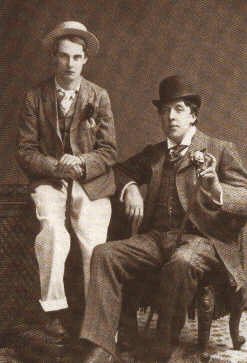

Wilde was at his literary peak in the 1890s and had developed a strong academic bond and shared an intimate friendship with Lord Alfred Douglas. Douglas was the youngest son of the ninth Marquess of Queensberry, John Sholto Douglas — an arrogant, ill-tempered, eccentric who vehemently opposed his son’s relations with Wilde, whom he regarded as a vile man. He intended to save his son from such “an evil companionship,” as he later described their relationship.

He even threatened to disown his son and “stop all money supplies” if their intimacy was not put to an end. When that didn’t work, he did everything he possibly could to damage the author’s reputation and tarnish his name.

Threatening restaurant and hotel owners with beatings if he heard that Wilde and his son were spotted together on their property was the first desperate thing he did. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the last.

16 Best Oscar Wilde Quotes

There was an unexpected “friendly” visit from a prized boxer to the author’s home in Chelsea. And on February 14, 1895, Queensberry showed up in front of St. James Theatre, ranting about Wilde and his alleged shameless, perverted lifestyle.

The Importance of Being Earnest was about to be shown for the first time, and Queensberry was disturbing everyone that came to see the show, including many prominent, influential figures from all over Europe. Wilde opted to bring charges against him for libel.

“I don’t see anything now but a criminal prosecution,” he wrote to Douglas, after his father left a calling card at the Albemarle Club with the note, “To Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite [sic].” It was Wilde’s favorite club where his wife was also a member.

“My whole life seems ruined by this man,” he wrote in despair.

The next day he and Douglas went to Travers Humphreys, a solicitor who after hearing them out, filed for a warrant. Lord Queensberry was arrested on March 2nd and brought to Vine Street Police Station.

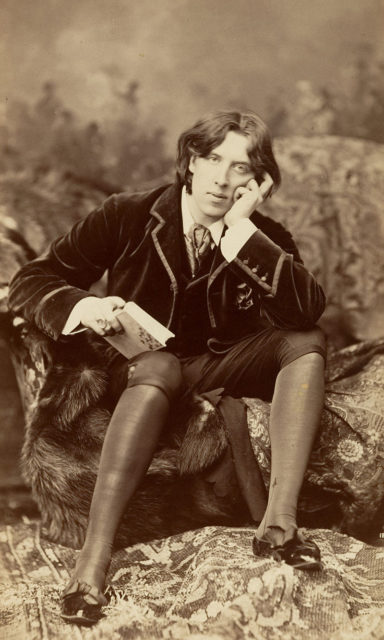

The trial at the Old Bailey began within a month or so, on April 3, 1985, with Wilde showing up in a stylish coat with a flower petal sticking out of the button-hole. His friends, including George Bernard Shaw, begged him drop the charges. They said it was a too risky endeavor, but he wouldn’t listen. And they were right. It went horribly.

Even though Sir Edward Clarke, one of the most prominent attorney’s in London, gave a grand opening statement and did everything he could to glorify his client, highlighting the gravity of the things done to him over the last couple of months, Lord Queensberry and his representative, Edward Carson, in their defense argued that their opponent had solicited 12 boys to commit sodomy between 1892 and 1894 and was liable for various acts of gross indecency.

Wilde was pulled apart during his cross-examination and was forced to withdraw the charges when the court found Queensberry’s description of him as a sodomite to be “legally justified” and “true, in fact.” His attorney advised him to do so: “I told him that it was almost impossible in view of all the circumstances to induce a jury to convict of a criminal offense a father who was endeavoring to save his son from what he believed to be an evil companionship.”

However, on April 5th, Carson presented copies to the to the court of the boys’ statements. “I hoped, and expected that he would take the opportunity of escaping from the country,” Clarke wrote, later on, fearing that Wilde would now be prosecuted under criminal charges.

Wilde had an hour and a half at least to catch the last train to France. Allegedly the local magistrate was aware of this but made no rush in issuing a statement for his arrest. Wilde stayed, and within a few hours was arrested at London’s Cadogan Hotel on twenty-five counts of gross indecency and conspiracy to commit gross indecency.

The first criminal trial, which began on April 26, 1895, ended as a mistrial. He gave a memorable speech about “the love that dare not speak its name” to justify his relations. At the second he was found guilty of all charges and was given the “severest sentence that the law allows.”

Wilde “did not want to be a coward and a deserter” and decided “it was nobler and more beautiful to stay.” Even though he believed, as he would later write in his most memorable work De Profundis, “I have got to make everything that has happened to me, good for me,” the two years with hard labor in the harshly punitive Reading Gaol were devastating to his wellbeing.

“We know not whether laws be right, or whether laws be wrong. All we know who lie in gaol is that the walls are strong and each day is like a year, a year whose days are long… The most terrible thing about it is not that it breaks one’s heart—hearts are made to be broken—but that it turns one’s heart to stone,” he wrote upon his release in his lengthy, heartbreaking poem “The Ballad of Reading Gaol.” It was the only thing he ever wrote after he got out and moved to Paris, where he was buried in 1900.