Sir Charles Leonard Woolley was one of the most prominent archaeologists of the early 20th century; his research methods, which were incredibly thorough and methodical, laid the foundations of modern archaeology and inspired future generations of extraordinary scientists.

Woolley is most famous for his groundbreaking discoveries in the ancient Mesopotamian city-state of Ur, located in present-day Iraq, which included neatly preserved extravagant tombs of Sumerian royals and the majestic Copper Bull, a sculpture dating back to 2600 BC which honors Ninhursag, the ancient Sumerian Mother Goddess.

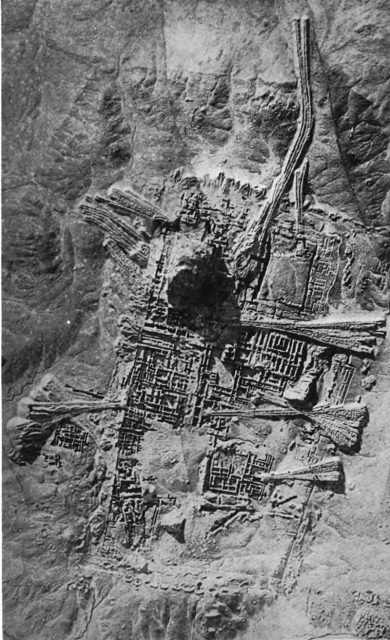

In 1925, while researching a palace on the outskirts of Ur that was built around 500 BC by King Nabonidus, the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Woolley stumbled upon another priceless gem of ancient history: the world’s oldest known museum. The site has unquestionably proven the fact that ancient cultures shared our love for the preservation of historical artifacts and research on the origins of humanity.

The discovery was purely accidental and unexpected. In several interconnected chambers within the palace complex, Woolley and his crew found a number of items that turned out to be much older than the palace; they were even older than the Neo-Babylonian Empire itself.

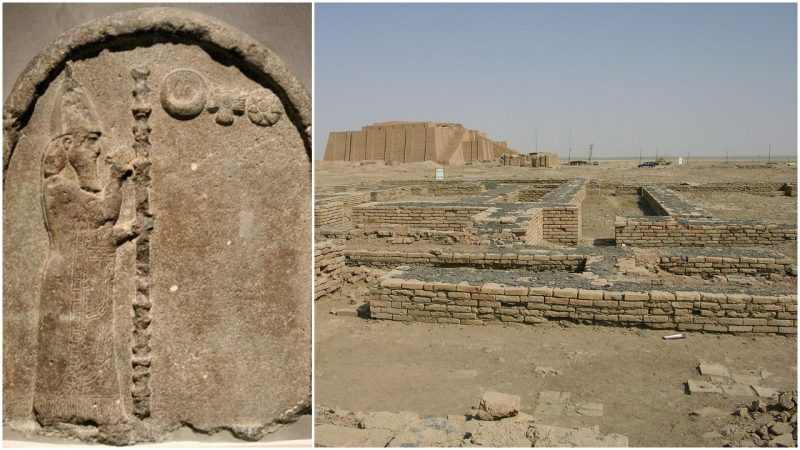

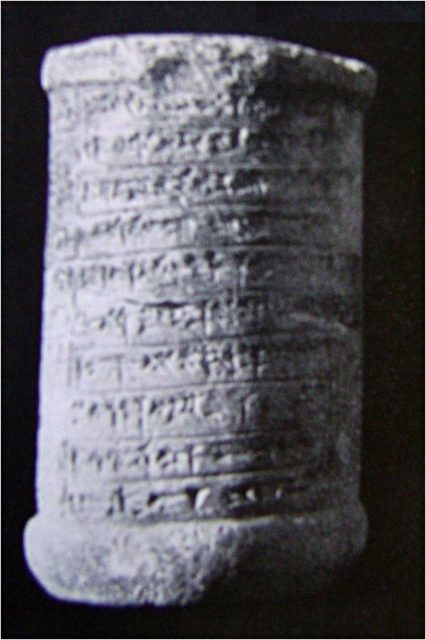

The assorted items included a fragment of an anthropomorphic stone statue inscribed with the name of “Dungi,” a king who ruled the Sumerian Empire from around 2029 to 1989 BC; clay tablets from the ancient Sumerian city of Larsa, dating back to 1700 BC; and a 1400 BC boundary stone with a blood-chilling curse and emblems of several gods engraved on its surface.

Woolley’s earliest notes on the discovery, which were published as a part of his book Ur of the Chaldees: A Record of Seven Years of Excavation, reveal that the acclaimed archaeologist was initially quite baffled with the unusual findings: “What were we to think? Here were half a dozen diverse objects found lying on an unbroken brick pavement of the sixth century BC, yet the newest of them was seven hundred years older than the pavement and the earliest perhaps sixteen hundred.”

However, subsequent research soon lifted the veil of mystery. It was determined that the items were a part of the vast collection of exhibits acquired by Princess Ennigaldi, also known as Bel-Shalti-Nanna, the daughter of King Nabonidus.

Most of the items had been excavated by the some King’s servants whose task was to explore ancient localities, but it is presumed that some had been excavated even earlier by the servants of Nebuchadnezzar II, the most powerful ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

World famous landmarks that are hiding something from the public

Princess Ennigaldi was a remarkable and influential woman who served as the High Priestess of Ur and ran a school for priestesses. According to Woolley, the chambers in which the items were found had been built specifically upon the Princess’ request, and she thus became the curator of the world’s oldest known museum.

It remains unknown whether regular folks were ever allowed to enter the museum, which is nowadays known as Ennigladi-Nanna’s Museum, but aristocrats of the time were undoubtedly able to feast their eyes on the intriguing collection.

The golden age of Princess Ennigaldi abruptly ended in 539 BC, when the Neo-Babylonian Empire dissolved and became a part of the vast and expansive Persian Empire which existed, in a number of different forms, all the way to the 20th century.

Princess Ennigaldi’s cultural achievements quickly drifted into obscurity and her museum was buried by time and dust. Still, thanks to the efforts of Sir Woolley and numerous other devoted archaeologists and anthropologists, it is now known that the Neo-Babylonians were progressive and curious people, who cherished their roots and their long and elaborate history. It is also known that the world’s oldest museum was curated by an immensely powerful woman.