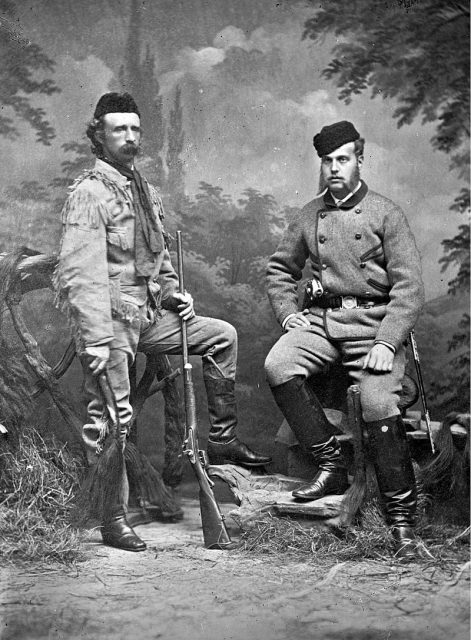

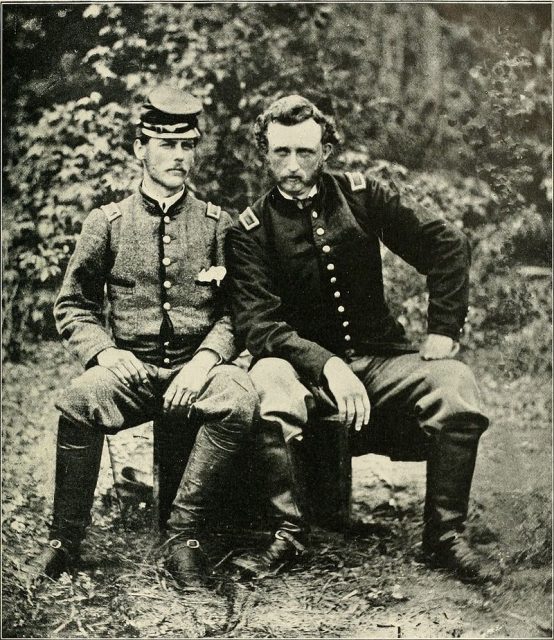

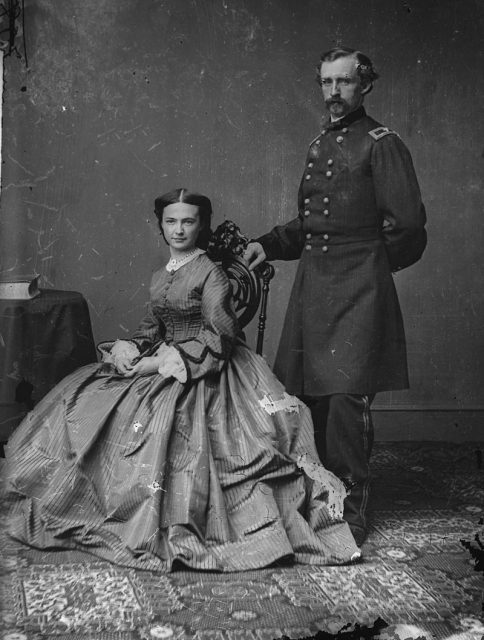

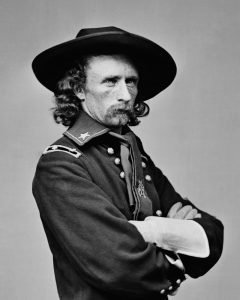

General George Armstrong Custer’s name is synonymous with the evolution of America as we know it today. He was a man who arguably lived fast and died young, aged 36. Custer became a hero of the American Civil War, known as much for his attention-seeking behavior as for his triumphs.

He also fell foul of his impetuous nature a few times, such as in 1867 when the war had been over a couple of years. The General was battling the Cheyenne, but the target turned out to be his own horse.

Worst of all, there wasn’t an Indian in sight. Custer was hunting buffalo at the time and gave chase when he spotted a potential trophy. Unfortunately, his aim was off and he wound up executing his steed with a surprise headshot. As PBS went on to relate, he was in quite a predicament following the accident: “On foot, bruised and totally lost, he had to be rescued by his own men.”

This wasn’t the brave and hardy soul who’d taken risks and helped Union forces beat back the Confederates. But then, as with all legends, a certain amount of the story was embellished. Custer was a military man yet also a showman. He wouldn’t have promoted the embarrassment of his dead horse.

However, there was a second equine that he was more than keen to show off, one he’d invested a lot of his time in. Don Juan was a striking creature, described in a 2015 article from the Smithsonian as “a beautiful thoroughbred stallion: more than 15 hands high; solid bay with black legs, mane and pert tail; and a proud, erect head.”

Custer rode the valuable horse without letting people know about one important detail. Don Juan wasn’t his. In 1865, with the Civil War over and the country slowly returning to some semblance of normality, the horse was taken from Clarkesville, Virginia. To the surprise of his groom, men in Union cavalry uniform arrived saying the stallion was theirs.

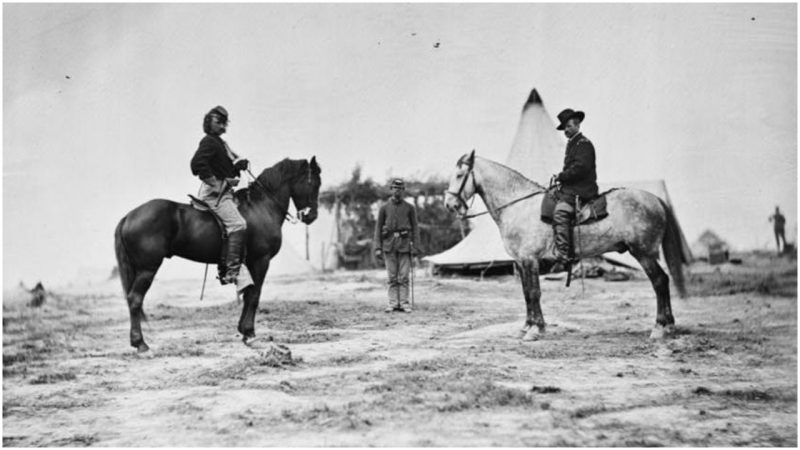

Ten days earlier Custer had been promoted to Major General. He appears to have viewed Don Juan as a spoil of war. He saddled up his prize for the Grand Review of the Armies, where the Union proudly marched through Washington D.C. to a rapturous reception. In a strange precursor of what happened in 1867, Custer suffered another horse-based calamity. This one wasn’t fatal, but it happened in full view of the assembled masses.

The crowds and the noise didn’t agree with Don Juan, who bolted when flowers were thrown at his rider in tribute. Custer got him under control and it certainly looked dramatic, but the public wobble wasn’t his finest hour. As the Smithsonian put it, “It was a splendid display of horsemanship, but also an embarrassing break in decorum… Custer sat astride his sin, and it had nearly proved too much for him.”

Cowboy slang we should all be using

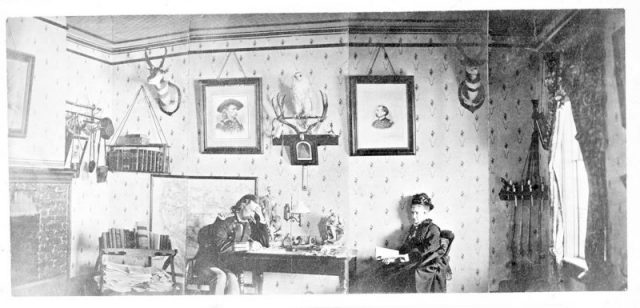

The article saw the troubled relationship between man and animal as indicative of a wider issue with Custer, namely a perceived decline in character. He could be flighty and tough, yet further qualities were added in the later stages of his life. It suggests the theft of Don Juan as a defining moment in Custer’s reputation, and a point from which the man’s ego arguably took the reins of his mind.

Don Juan’s true owner was Richard Gaines, who unsuccessfully pursued Custer to retrieve his property. Unfortunately for Gaines, the hero of the Civil War had some powerful friends, and he couldn’t wrangle the horse from his clutches.

That frustration may have turned to grim amusement after what occurred in 1866. Custer had paraded Don Juan at the Michigan State Fair, in the hope of cashing in on his investment. His career had moved from the heat of the battlefield to the comfort of high society and he hoped to make his home among the entitled.

There was an ironic twist to the tale. A month after appearing at the fair, Don Juan passed away. The cause of death was not a gunshot, but a burst blood vessel.

The Smithsonian presents the story as something that put the brakes on Custer’s increasingly arrogant outlook. An individual who made his name on the cusp of great change in his home nation. And also someone who ultimately could not adapt to life in its wake.

“Custer represented the Republic’s youth, the nation as it had been and never would be again. Like much of the public, he held to old virtues but thrilled to new possibilities. Yet whenever he tried to capitalize on the new America, he failed—beginning with a stolen horse named Don Juan.”

Read another story from us: The life of Queen Ankhesenamun, sister and wife of Tutankhamun

When Custer snuffed out his ride the following year, it had the hallmarks of a major error in judgment. The incident was also bizarrely appropriate, reflecting the soldier’s complex interactions with horses.

Steve Palace is a writer, journalist and comedian from the UK. Sites he contributes to include The Vintage News, Art Knews Magazine and The Hollywood News. His short fiction has been published as part of the Iris Wildthyme range from Obverse Books