Rooftopping – that dangerous and bizarrely trendy “hobby” of adrenaline junkies seeking a sky-high thrill – is actually not a new phenomenon at its core. While the social media aspect of it may be, it was once a necessary part of construction work.

Anyone who has ever visited a college dorm has likely seen the famous image, appropriately titled “Lunch atop a skyscraper, 1932,” of construction workers in New York City taking a much-deserved break. They are sitting on a steel girder, suspended in mid-air, hundreds of feet above the ground, chatting and sharing a meal. It is enough to make anyone’s heart skip a beat.

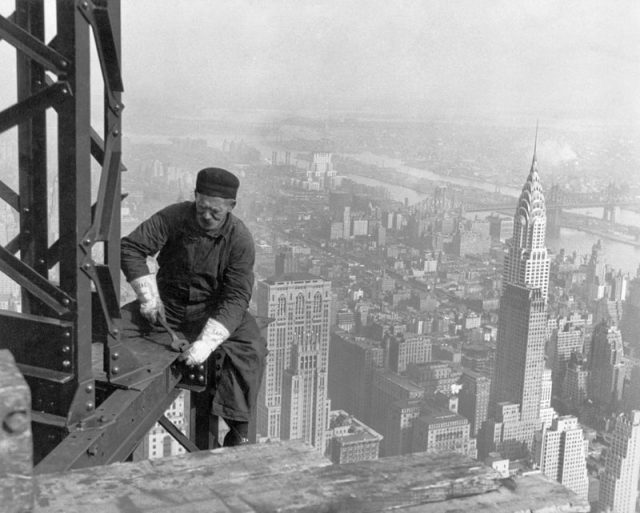

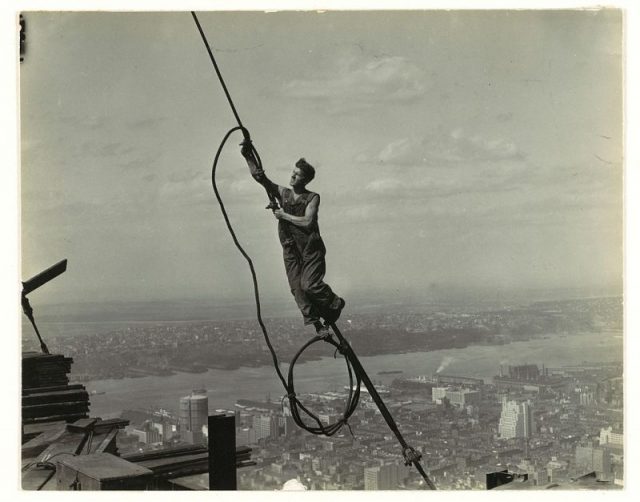

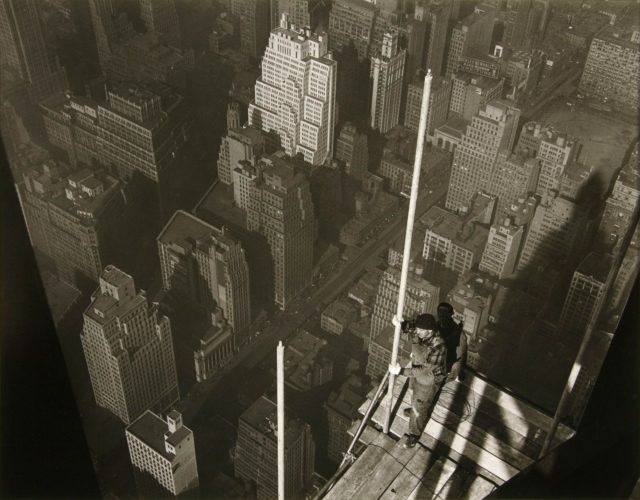

While the photo was actually staged, that construction workers in the early 20th century would have to be out on these girders and other beams very high above the ground is not fiction. The famous high rises of the era – the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Centre – were not made with the same types of cranes and other construction machinery we have today. Rooftopping, as it is known today, was simply a part of the job.

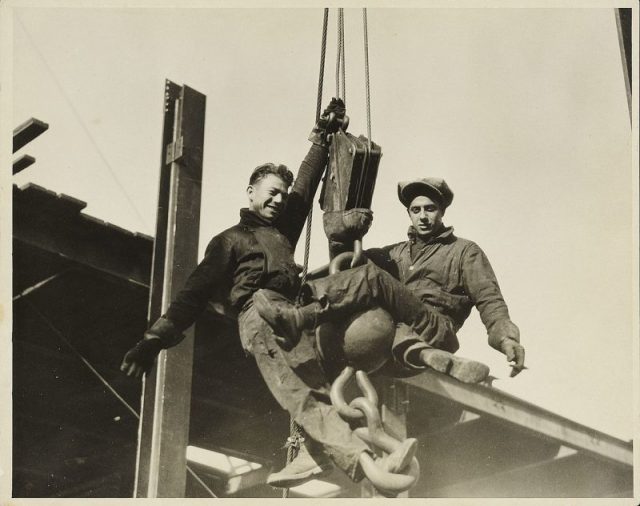

It takes a certain person, with a certain constitution, to be able to do high-rise construction work today, but that was especially so in the 1920s and 30s. Safety equipment was not what we see today, if present at all.

Photographs exist of workers perched on the edges skyscrapers under construction, riveting, welding, doing what they do best, with little to no safety equipment, except perhaps good thick gloves. Hardhats were not even used, let alone harnesses in most cases.

World famous landmarks that are hiding something from the public

Lewis Hine, a photographer who was employed to record the building of the Empire State Building, described these workers as courageous heroes, and it is easy to see why in his images.

Interestingly, the construction of the Empire State Building involved some particularly adept individuals. While workers were employed from both the U.S. and Europe, hundreds were hired from the Kahnawake Mohawk reservation near Montreal, Canada.

The Mohawk had been involved in construction at high levels since 1886 on a project over the St. Lawrence River, and members of the Indigenous nation were believed to have no fear of heights (it was later stated by Mohawk member Kyle Karonhiaktatie Beauvais in 2002 that they were afraid of heights; they just handled it better).

By 1916, they were working on almost all of New York City’s major construction projects, and several moved their entire families to Brooklyn to avoid the long commute home at the end of the week, becoming residents of the area.

Photographing these death-defying laborers became popular at the same time. Whether by dare or coercion, many photographs exist of workers going about their day, as well as many that are staged and set up. However the images were produced, the fact remains that construction workers were still rooftopping long before the trend ever became a social media sensation.

Perhaps astonishingly, when one looks at the photographs and the conditions in which these men worked, only 5 people, out of a total of 3,400 workers, were killed during construction of the Empire State Building. This is remarkable when compared to the construction of the original World Trade Center in the 1970s, when 60 people lost their lives, even though better safety equipment was available.

Similarly, the Chrysler Building, erected in 1928, recorded no deaths at all during its construction. In fact, if we look at death rates per 1,000 workers, the Panama Canal holds the record to being the deadliest construction project with 5,609 dying during the U.S. construction period alone (estimates are as high as 30,000 for the total project, but this may never be confirmed). Many of these deaths were due to jungle hazards, such as malaria and yellow fever, as well as bubonic plague, in addition to accidents.

Read another story from us: New York’s 1977 blackout shone a light for the hip-hop movement

Rooftopping may be the domain of thrill-seekers today with a desire to become famous on social media, however, it was once a necessary, and perhaps even more dangerous aspect of ordinary work. Men risked their lives every day for a paycheck, not for kicks, or fame and fortune. It would be interesting to hear what they think of rooftoppers today.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career. She has lived and traveled all over Canada and Europe.