If you ask the average person to think of the only painter from the School of Paris whose statue stands in the Montparnasse quarter, they are not likely to come up with the name Chaim Soutine. An exhausted tourist wandering around Gaston Baty Square might come across a clumsy figure of a bronze stranger slouching in his baggy coat, eyes covered with a shabby old hat. He stands there, hands in his pocket, lonely and detached from the world just as the great artist used to be when he was alive.

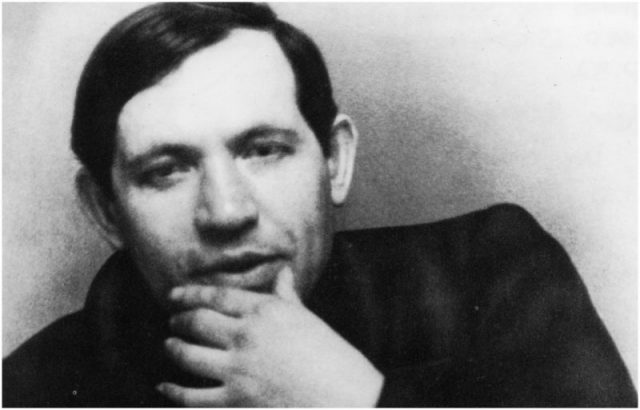

Chaim Soutine (originally Haim Sutin) was born in 1893 in the tiny village of Smilavichi in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Belarus). He had ten siblings, which is why Chaim had to take any work possible to help his parents make ends meet. Being a peculiar child, oddly quiet, aloof and lost in thought, he couldn’t manage any other activity besides sketching.

Due to the constant lack of money, it was strictly forbidden for the boy to draw. His artistic skills were of no use to the starving family, so he had to steal things from home and trade them for chalk and pencils. Severe punishment followed immediately, though to no avail, as right after being released from the dark cellar, little Chaim would do the same thing again. Protecting her son from his father’s anger, Soutine’s mother sent him to Minsk to obtain a position of photo editor. The events that followed changed his life drastically.

One day Chaim secretly drew a portrait of the local rabbi, which is considered unacceptable in the Jewish tradition. Having seen the drawing, the rabbi’s son, a butcher, attacked the artist almost beating him to death. After a short trial, the butcher was to pay Soutine 25 roubles, an amount that made it possible for him to move to Vilnius, Lithuania and enter art school.

In 1913, the completely broke 20-year-old painter left Vilnius for Paris. Full of hopes and expectations Chaim found his shelter in a place called “La Ruche” (French for the beehive). It was an odd-looking, round, three-story building that resembled a hive rather than the dwelling of a refined bohemian crowd. Small, narrow studios of La Ruche were basic but cheap to rent and thus attracted many struggling artists of Paris.

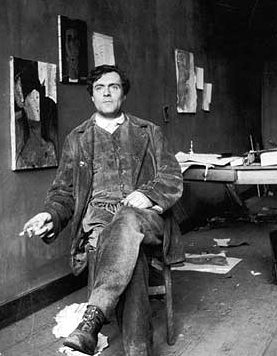

At last, Soutine found himself surrounded with people of exceptional talent and creativity such as Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, Guillaume Apollinaire and Marc Chagall. The latter’s memories suffice to describe the living conditions in the Hive. Chagall would recall that one had no other choice but to die there of cold or become famous.

Soutine’s eccentric behavior made people feel awkward in his presence. Having been raised in poverty, he had no basic hygiene routine let alone any knowledge of proper social etiquette. He spoke very basic French and could barely make himself understood. Once again lonely and disregarded, Soutine would find consolation in work to isolate himself from his fellow-painters.

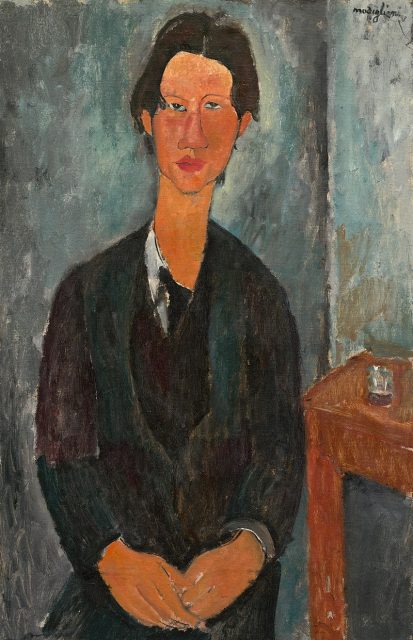

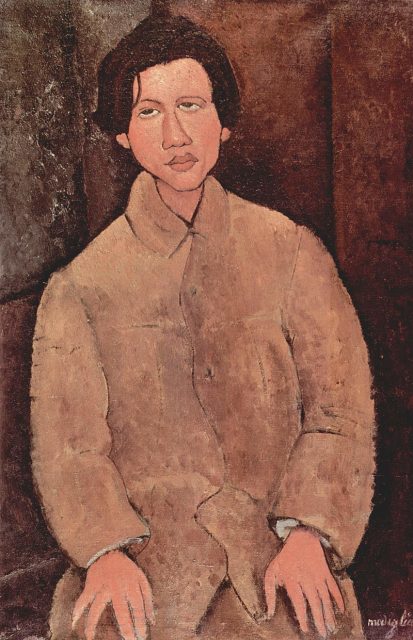

It was Amedeo Modigliani who took Chaim under his wing, presented him with a toothbrush and a piece of soap and taught him how to make useful acquaintances. Soutine’s unconventional character fascinated and entertained Modigliani, and the two soon became close. Hungry for artistic experience, Chaim often followed his new friend to the Louvre and, after hours of admiring the art of the Quattrocento, he would return home to create something of his own.

One of the obstacles on the way to making art was that Soutine could barely afford to buy paints and canvases. And again Modigliani would come to the rescue, providing the necessary art supplies and begging models to sit for the strange painter, who besides being suspiciously quiet, had a habit of working completely naked. Such eccentric fashion was not a whim but a simple lack of choice, as Chaim possessed only one suit, which he didn’t wear while painting for fear of staining and thus ruining it.

Constant malnutrition and the consumption of alcohol resulted in acquiring an ulcer that would bear him the most dramatic consequences years later. A Russian poet Marc Talov happened to witness Soutine painting his Still Life with Herring: “Before eating the food that he had brought from the store, he took on a still-life and worked in agony, torn by hunger but devouring it only with his eyes, not letting himself touch anything until he finished the work. He became demonic, drooling from the very thought of the upcoming royal dinner.”

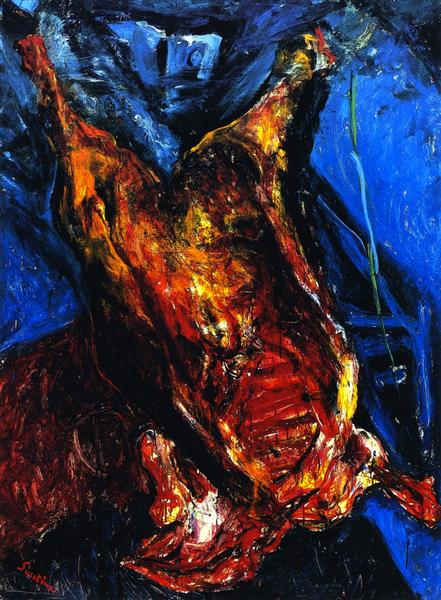

The Hive was situated close to a slaughterhouse and, overwhelmed by the sight of the bleeding carcasses, Soutine would secretly bring them to his room and start painting. The image of a slaughtered bull became symbolic for the artist, a tragic representation of innocence accepting its violent and inevitable death.

The painter would later confess: “I once saw the butcher’s knife cutting the throat of a rooster spilling its blood. I wanted to cry but the butcher’s face, beaming with satisfaction, halted the cry in my throat. When painting Carcass of Beef, I was longing to free myself from that cry, but I still haven’t succeeded in that.” So he carried on painting, terrorizing the inhabitants of the Hive with the unbearable smell of rotting corpses. There was a story among the residents of La Ruche that when Marc Chagall first spotted the blood leaking from underneath Chaim’s door, he ran away screaming, “Someone has killed Soutine!”

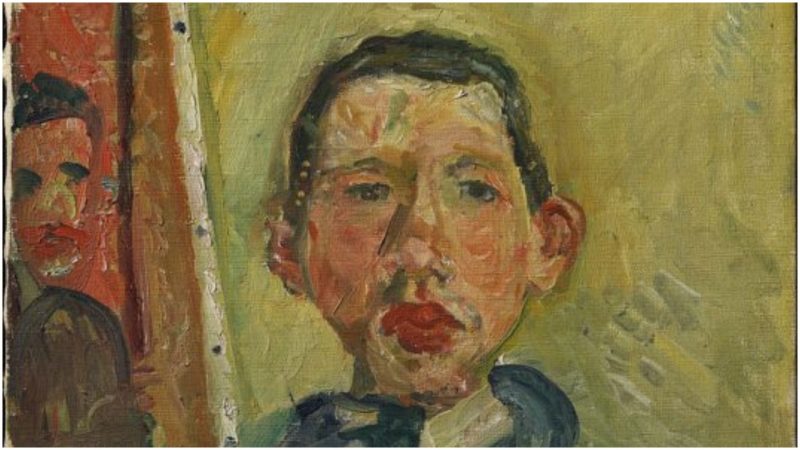

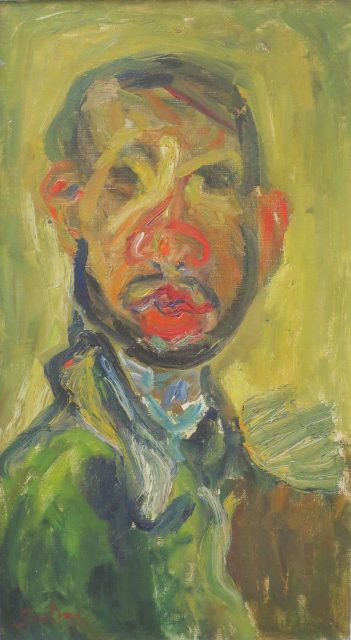

Although he worked with passion producing paintings one after another, it took some time and a fair share of luck before Soutine gained the recognition of Parisian art dealers. Regardless of the subject, color was the dominant aspect of his art. Vibrant, saturated, expressive, it would explode onto the canvas to fill every bit of space. His style was dramatic, emotional and almost too disturbing to attract potential buyers, so it was a surprise even for Soutine when in the 1920s his paintings suddenly became popular among prominent American collectors.

Throughout his life, the artist had personal exhibitions both in Europe and the U.S. After gaining unexpected success, Soutine continued to paint still-lifes as well as portraits and landscapes, working without rest, trying to improve his skills and technique. In attempts to master his style to perfection, the artist would buy his own paintings from private collectors to change or destroy them.

When WWII broke out, Soutine had no other choice but to flee from occupied Paris to Normandy. Trying to save his pictures from the Nazis, he gave some of them to the local farmers. Later, Soutine’s friends helped him return to Paris under disguise to undergo an emergency stomach surgery, which was of no success.

Read another story from us: Decadence and Controversy: the Art of Aubrey Beardsley

In 1943 the artist succumbed to an ulcer. He died alone while being secretly transported back to safety in a burial hearse. Referring to the dramatic style of his paintings, Soutine was once told: “Something terrible must have happened in your life.” The painter replied: “How could such an idea occur to you! I have always been a happy man.”

Julia Robakidze is a professional linguist specializing in English philology with a Master’s degree in Translation. She spends her time teaching English and exploring art museums around the world.