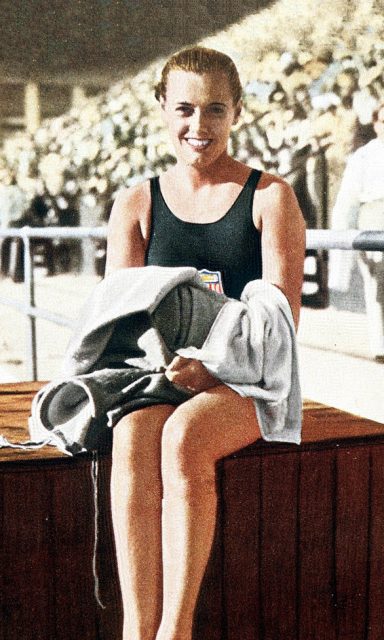

Competitive swimmer Eleanor Holm, in her day, was as dominant an athlete as Serena Williams or Katie Ledecky. In 1932, she captured gold in the 100-meter backstroke at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics and set no less than seven world backstroke records during her career.

Holm was poised to add to all that hardware at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. But her quest for gold came crashing down, in what would become one of the most-publicized scandals in sports history.

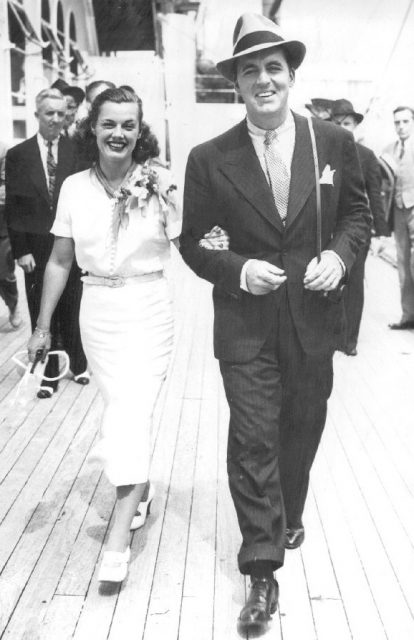

Holm was a beautiful, feisty, no b.s. Brooklyn girl, who learned to swim at a pool near her family’s summer home in Long Beach, N.Y. She attended Erasmus Hall High School and married a fellow graduate, Art Jarrett, a bandleader and singer, in 1933, at age 20, after a five-month romance.

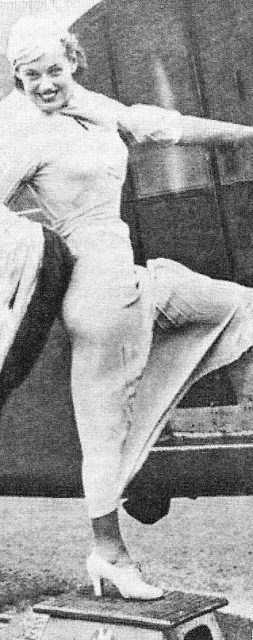

Holm would appear in some of his shows — in one memorable performance, singing “I’m an Old Cowhand” while dressed in a bathing suit, cowboy hat, and heels. She also landed a few small roles in Warner Brothers movies. But the pool is where Holm shot to fame.

On July 15, 1936, the S.S. Manhattan, carrying some 350 Olympians, left New York Harbor and set sail for the Berlin Games. Later that evening, Holm was invited to an all-night cocktail party on the first-class deck.

Her carousing drew the ire of the higher-ups, particularly Avery Brundage, the kill-joy president of the American Olympic Committee. Still, the fun continued during a stopover in Cherbourg, France, where Holm handily won a couple of hundred dollars playing dice.

That night, yet another party. In an interview for the book All That Glitters Is Not Gold, by William O. Johnson, Holm recounted: “This chaperone came up to me and told me it was time to go to bed. God, it was about 9 o’clock, and who wanted to go down in that basement to sleep anyway? So I said to her: ‘Oh, is it really bedtime? Did you make the Olympic team or did I?’”

That cinched it. The chaperone went storming off to Brundage, complaining that Holm was setting a poor example for the rest of the team. The next morning, officials informed Holm was told she wouldn’t be competing in the Games, citing excessive drinking and curfew violation.

Today, in the age of steroid popping, hotel trashing, and knee-cap bashing, the transgressions seem fairly tame, but at the time, Holm’s behavior made headlines around the world.

One of the stories going around was that Holm was severely intoxicated and close to comatose. Holm vigorously denied that version of the event, copping only to a few glasses of bubbly. Besides, she pointed out, there was no ban on alcohol and many of her fellow athletes had been indulging, as well.

Despite a petition to re-instate the swimmer, signed by 200 team members, Brundage wouldn’t budge. Holm believed that her “pink slip” was the result of a personal grudge.

“I was everything that Avery Brundage hated,” she recounted in the book Tales of Gold, by Lewis H. Carlson and John J. Fogarty. “I had a few dollars, and athletes were supposed to be poor. I worked in nightclubs, and athletes shouldn’t do that. I was married.’”

No matter, Holm would have the last laugh. “He did make me famous,” she would say of her no-nonsense nemesis, years later. “I would have been just another female backstroke swimmer without Brundage.” Indeed, Holm became the toast of Berlin, hired by the International News Service to file reports on the Games.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/TDn8zkochFc

She also attended a reception held by Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders, including Hermann Goering, who gifted her with a silver swastika from his uniform. After the Olympics, Holm re-fashioned herself into a celebrity of sorts, showing those who came later — Esther Williams for one — that it was possible to parlay Olympic glory into a show business career.

She appeared in the 1938 movie Tarzan’s Revenge, playing alongside 1936 Olympic decathlon champion Glenn Morris, then joined another fellow Olympian, Johnny Weissmuller, doing 39 shows a week in the music, dance, and swimming extravaganza “Aquacade” at the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940. The show was the brainchild of impresario Billy Rose (nicknamed “The Little Napoleon of Showmanship”).

After her divorce from Jarrett in 1939, Holm and Rose would get hitched, following a very public affair. (Rose was married to famed Ziegfeld comedienne Fannie Brice at the time.) The adulterous goings-on would play out on the big screen in the 1975 Barbra Streisand musical Funny Lady.

Holm and Rose divorced in 1954. Twenty years later, she tied the knot with Tom Whalen, a retired oil executive, and moved to Miami. Though Holm kept a few souvenirs from her days in the water — among them, the red, white and blue bathing suit she wore in the 1932 Olympics — she would give up swimming in favor of tennis.

Holm also abandoned her drink of choice. “I don’t drink Champagne anymore. Just a little dry white wine,” she would tell Dave Anderson of The New York Times in a 1984 interview. Holm died in 2014, at age 91 — with, we’re guessing, not a single regret.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.