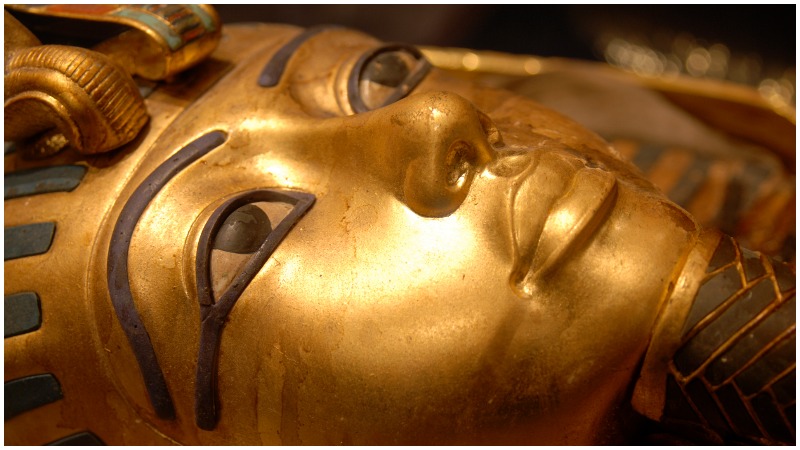

In 1848, Mihajlo Baric, a Croatian official in the Hungarian Royal Chancellery, resigned his position and went traveling. His journey took him to Alexandria, Egypt, and while he was there, he bought a sarcophagus containing a female mummy as a souvenir, according to Ancient Origins.

Much of Europe was in the throes of the Egyptomania that began when Napoleon Bonaparte launched a military campaign in Egypt in 1798, bringing with his army various scholars and scientists. When Baric made his trip, Egyptian artifacts were still in very high demand across Europe.

When he returned to Vienna, Baric unwrapped the mummy, and displayed her upright, in his sitting room. The wrapping was put in a glass case, and also displayed. On Baric’s death in 1859, his brother, a priest, inherited the artifacts.

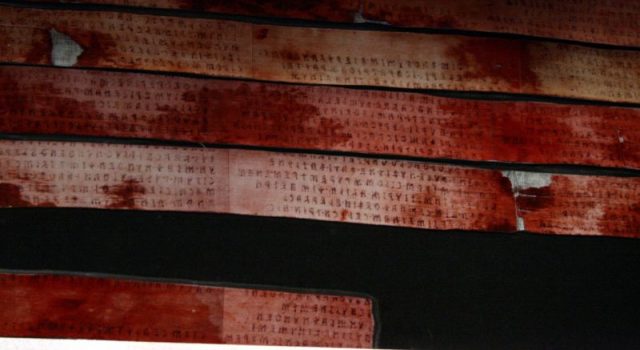

He, in turn, donated both the mummy and its wrappings to the State Institute of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia, which is now known as the Archaeological Museum of Zagreb. It wasn’t until the mummy’s arrival at the Institute that someone observed what were writings on the linen of the mummy’s wrappings.

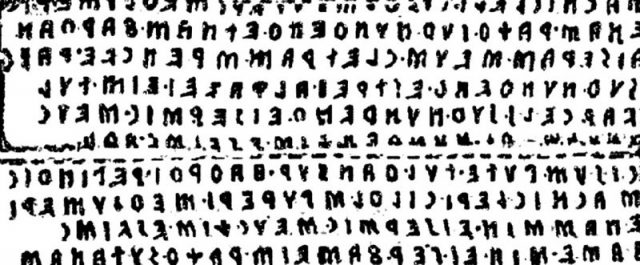

Heinrich Brugsch, a German Egyptologist, noticed the writings, but assumed they were Egyptian hieroglyphs and didn’t do anything further. Ten years later, in a random conversation with explorer Richard Burton, Brugsch finally realized that the language was a different one altogether. The two men understood the script was probably significant, but they thought it may have been an Arabic translation of the Book of the Dead.

The wrappings were sent to Vienna in 1891, and were looked over by an expert in the Coptic language. The expert finally concluded that the writings were, in fact, Etruscan and could put the wrappings in their proper order but couldn’t make a solid translation.

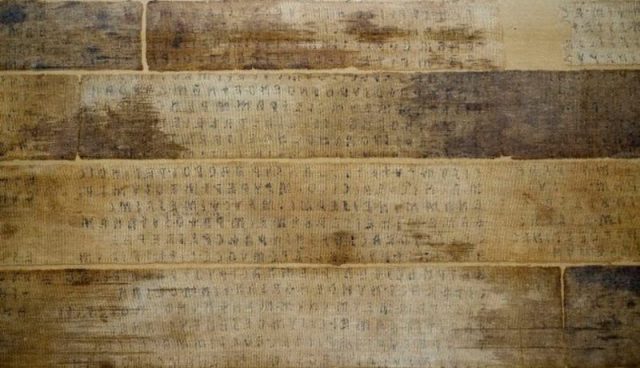

The Linen Book of Zagreb, as the wrappings are now known, is the longest Etruscan text ever discovered, and the only linen book dating from the 3rd century B.C. Most extant writings in Etruscan are short and fragmented, and much of the language remains unknown.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “Etruscan” refers to members of a people who hailed from Etruria, Italy, west and south of the Apennines, and between the Tiber and Arno.

The Etruscans had the first great civilization on the Italian Peninsula. Many of their customs were later adopted by the Romans, who became the next great civilization on the peninsula. The Revolvy discussion of the Linen Book says that, based on paleographic evidence, the book dates from 250 B.C., and that mentions of specific local gods place it as having its origin somewhere in a small area in south-east Tuscany, near Lake Trasimeno, where there were known to be four Etruscan cities.

Although so little of the Etruscan language is understood, enough words have been picked out of the text to give the general idea of its content. There are names of gods and dates all the way through the text, suggesting it is a religious calendar noting dates for various religious rituals. This idea has been reinforced by experts having found words and phrases that appear to have liturgical meanings.

All of this begs the question of how a Etruscan religious document ended up wrapped around a mummy in Egypt. Ancient Origins suggests that one possibility may have been that the mummy was a wealthy Etruscan traveler, who fled to Egypt as the Romans were invading their home.

The woman was embalmed before her burial, which was the norm for wealthy foreigners at that period of time, and the presence of the book could be explained as a part of Etruscan burial customs.

The problem with this idea, however, it that a piece of papyrus scroll was buried with mummy, which identifies the body as being that of an Egyptian woman, Nesi-Hensu.

The presence of the scroll strongly suggests that the mummy and the book it was wrapped in are not connected at all, and it just happened that linen with the foreign writing was handy when the embalmers needed it. It may be nothing but coincidence, but it still gave scholars the longest Etruscan text ever found.