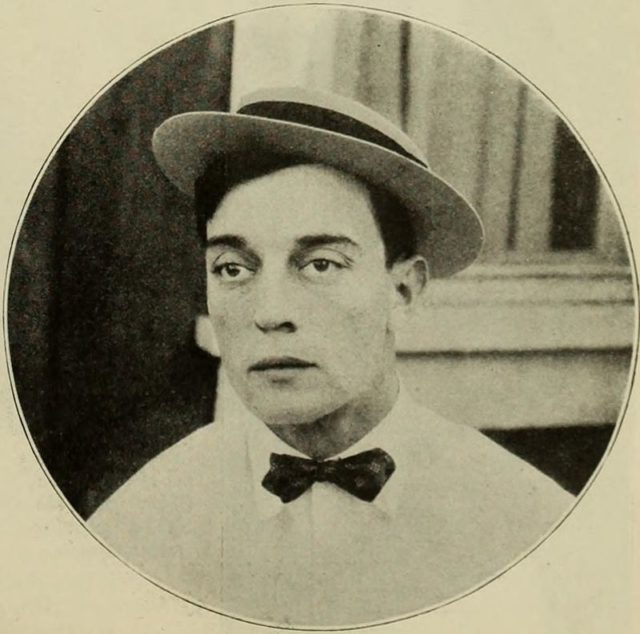

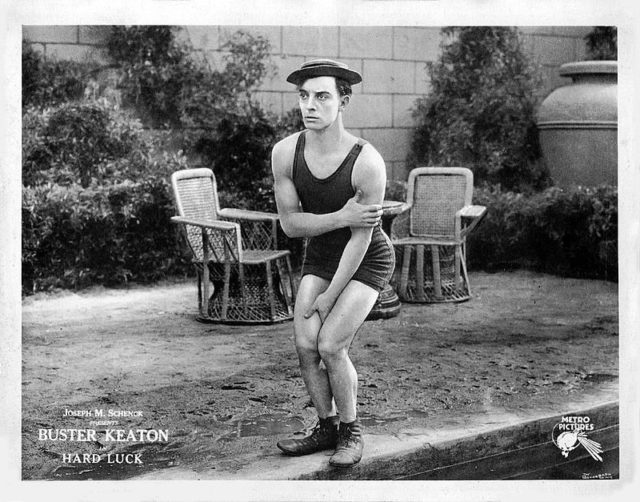

Throughout the 1920s, Joseph Frank “Buster” Keaton was a comedic force of nature on the big screen. Then, as the decade drew to a close, his influential brand of extreme slapstick and stunt work hit a bump in the road.

The result was a descent into alcoholism and depression that became so bad it led to Keaton being institutionalized. But how had it come to this? Buster blazed a trail through silent Hollywood, and seemed to have it all. Why did it fall to pieces, and how did he wind up in an institution…?

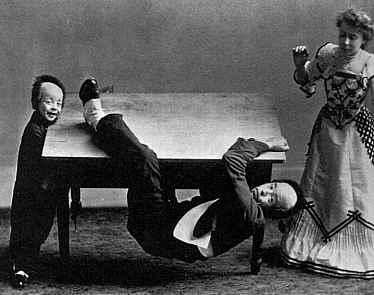

It has been speculated that his early life played a role in the eventual collapse. He was raised in vaudeville, where father Joe would throw him through the air like a football. As mentioned in his entry for Biography.com, Keaton was “Working with his parents in an act that prided itself on being as rough as it was funny.”

This roughness extended beyond the boards to the accident which gave rise to his legendary nickname. It supposedly came from Harry Houdini, who picked up young Joseph after the boy had fallen down a flight of stairs and, according to Biography, exclaimed: “That was a real buster!”

Keaton Sr. was reportedly a heavy drinker. The 1995 book Buster Keaton: Cut To The Chase by Marion Meade highlighted the comedian’s background in an attempt to shed light on the performer’s demons. A review on Publishers Weekly says that Joe “beat him at the first sign of fear” and that “Keaton left his uncaring parents and began acting in silents.”

In response to a review in the New York Times, Bruce Levinson of Damfinos (the International Buster Keaton Society) took issue with this characterization. He claims “Ms. Meade’s view that Keaton’s on-screen character was a direct manifestation of alleged brutality by his father does not withstand scrutiny… Subjecting great artists to child psychology almost 90 years after the fact is a risky endeavor.”

Levinson points to a lack of evidence, alongside no indication from Keaton that his younger years were troubled. As for the on-stage violence, “knock-about comedy was far from unusual. Chaplin and Lloyd were often assaulted in their films.”

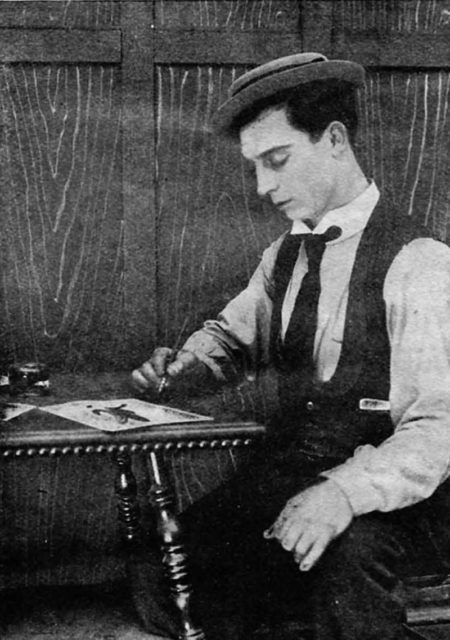

While it’s debatable Keaton’s family life was the root of his deterioration, one factor that certainly bothered him was his marriage. The seemingly indestructible man married actress Natalie Talmadge in 1921, though wedded bliss did not last long.

It’s said Talmadge wanted a separate bedroom following the birth of their two sons. Then there was the question of finances, with Mrs Keaton not averse to spending large portions of her husband’s salary.

With his home life fracturing, Buster suffered another blow, this time in the form of artistic differences.

He’d been working with total control up until 1926, but then he made a picture that hit the aforementioned bump… The General. A 2014 article in The Telegraph described the expensive Civil War-set comedy as having “suffered from great expectations, following a run of crowd-pleasers… reviewers struggled with the ironic treatment of North vs. South, and the film lost money.”

By getting political, Keaton had cooked his creative goose. The relative failure of the film, combined with the onset of “talkies” in 1927, took the star to MGM, where in 1928 he signed a deal that reduced his creative input. The contract was terminated in 1934.

These pressures certainly set Keaton on a self-destructive path. His drinking was out of control, and he famously married nurse Mae Scriven in 1933. He was so inebriated at the ceremony that he later claimed not to remember it.

So it’s little wonder that, no matter how much one particular factor may have contributed, he found himself confined to a place of safety. The show didn’t end there, however.

In the So Funny It Hurt documentary for TCM, it was revealed he channeled Harry Houdini to slip out of a straitjacket. How he did it? Well, you’d have to go back and ask Houdini. He then went on to marry a nurse at the institution but claimed to never remember it. Buster Keaton was arguably at his lowest ebb, yet despite this, he remained a master of trickery, and a consummate professional.