In 16th century France, divorce was a rarity, reserved only for the well-to-do and possible only in exceptional cases.

The only reason for a couple being granted a divorce was of a strictly sexual nature — if the man was unable to perform his marital duties.

Inability to do so was seen as an act against the Church, as the purpose of a marriage was to procreate.

According to Mary Roach, author of The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex, not having sex with your spouse, whether it be due to a physical or psychological nature, was considered a crime throughout 16th and 17th century France.

French Historian Pierre Darmon found that the first cases of divorce caused by impotence were documented in the 14th century when the ecclesiastical courts faced “a tidal wave of accusations.”

It is still not completely clear how the whole process took place, but Darmon’s fascinating book Trial by Impotence offers us some insight.

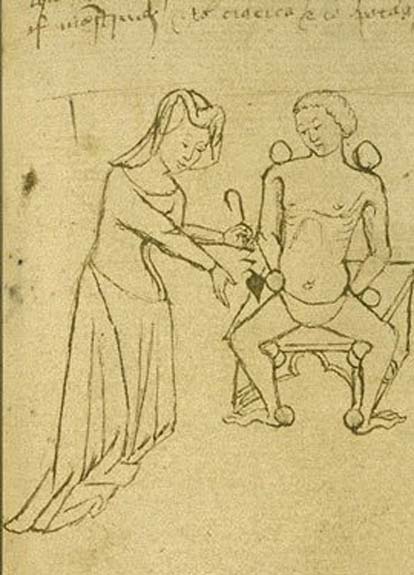

It started with the accusation of the unsatisfied wife who had to raise the claim in front of the court. Later, the accused party was examined in front of the celibate priests and clergymen, surgeons and midwives.

The examination focused on the reproductive organs of men under suspicion. Laura Bannister writes: “A husband’s natural parts were scrutinized for color, shape, and number—the best thing he could hope for were inspectors of delicate demeanor. Various hypotheses were tested. Could he muster an erection? Expel reproductive fluids on demand? Was he capable of healthy performance, or had he been forcing his partner into lascivious positions without the promise of coming children?”

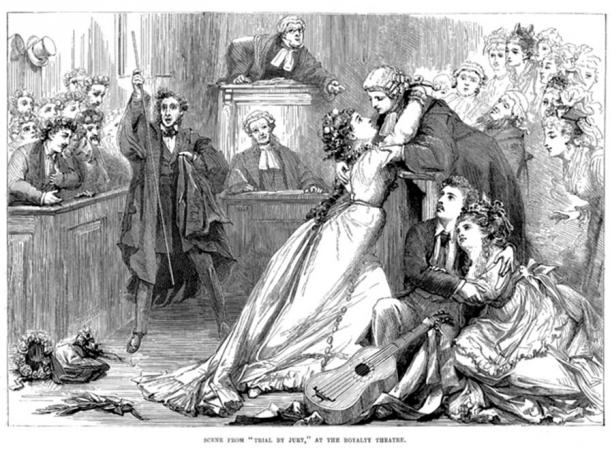

Parisian pamphleteers (an equivalent of today’s tabloids) were keen to write about ongoing trials. This meant that the nobility readily discussed the cases in question, bringing public humiliation to the accused party. The only way to refute the decision of the court was to proceed to the so-called “Trial by Congress.”

According to Tony Perrottet, the trial was held at a neutral territory, where the couple “performed” in front of experts who would make a final judgement.

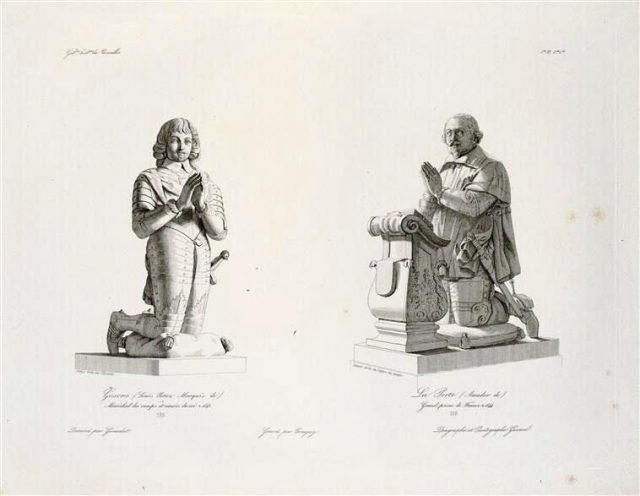

There are two documented cases that teach us how the whole thing looked for a French nobleman. One is of Marquis de Gesvers in the 18th century, and the second of Marquis de Langey in the 17th century.

According to Riley Winters writing for Ancient Origins, Marquis de Gesvers was accused by his wife Mademoiselle de Mascranny as being impotent three years into their marriage. He did not undergo the Trial by Congress, but his genitals were thoroughly inspected.

The outcome was not completely devastating as the experts observed an erection, but still claimed that he was unable to procreate. Due to the limited medical knowledge of the time, the ability to have an erection was not speaking against impotence.

He was saved from divorce only by his wife’s unexpected death.

Marquis de Langey, on the other hand, suffered harsher consequences and had to undergo the notorious Trial by Congress.

He was declared healthy after the first examination, but he demanded the final trial in order to redeem his name.

It is not clear what led to it, but his potency diminished when he had to perform the act under scrutiny. Much to his wife’s delight, he was declared impotent and she was granted a divorce.

Read another story from us: 5 Famous Paintings with Crazy Hidden Images

Even though these trials may seem unthinkable now, they were common practice not only in France, but also in England. Consummation and procreation were the end goals of a marriage in pre- and post-medieval times in Europe. Riley Winters writes: “Consummation was, after all, Henry VIII of England’s reason for divorcing his first wife.”