What is our fiction world without monsters? Perhaps unnecessarily boring and dramatic.

Monsters have existed in film since the very early days. Before CGI opened the gateway to new, mind-blowing creatures, monsters were created with blood, sweat, and tears.

Hours of makeup and patient sitting for the actor depicting the monster, all kinds of props to achieve those hairy King Kong visuals, and excessive use of camera tricks is what brought monsters to 20th century movie theaters.

Some of them went on to be timeless Halloween hits, too.

Frankenstein (1931)

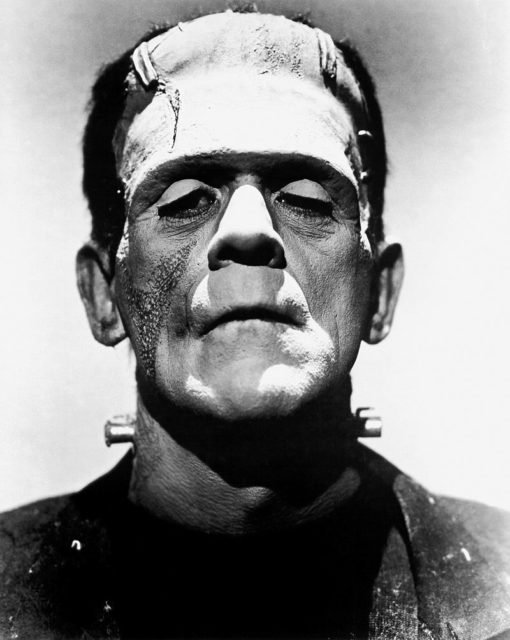

In the early 1930s, top billing actor Boris Karloff got the serious task of portraying one of the earliest sci-fi characters out there — that of Frankenstein’s monster, the brainchild of writer Mary Shelley. She invented this tragic character in her 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus.

Karloff was transformed into The Monster with the help of supreme makeup master Jack Pierce.

For the movie, cotton and gum were used to accomplish the effect of the monster’s abnormally flattened head.

On the set, Karloff also had to wear bulky platform boots, each one weighing 13 pounds, a double set of pants and an extra short jacket.

The low camera angle used for filming scenes with Karloff further added to the frightening effect of his character.

It is said Karloff sometimes went in bed with his makeup on. It was his attempt to save himself from the trouble of extensive hours of applying the makeup again the following day.

Pierce also applied greasepaint on his face, so it’s a miracle if the man managed to get any proper sleep going to bed with all of that.

Dracula (1931)

That same year, 1931, saw another hair-raising villain in theaters.

The film about the most famous vampire in the world was directed by Tod Browning and in it, a lesser known actor from Hungary took the role of the blood-sucking monster. It was this iconic portrayal of Count Dracula that brought Bela Lugosi international fame.

Lugosi was already well acquainted with his villainous character, having played the role in a six-month run on Broadway in 1927, and the subsequent tour of the production through 1928-9.

Lugosi took care of Dracula’s makeup and outfit partially by himself. The studio wanted him to wear fangs, but he refused. He sported a spotless tuxedo and delivered an enticing, refined image of his monster, one that we now embrace each Halloween season.

In some scenes Lugosi appears with a medallion below his bow-tie, which some have speculated was an item personally belonging to him.

Lugosi’s portrayal of Dracula differed from previous visualizations of the vampire. Nosferatu released as a German Expressionist horror in 1922, showed a Dracula that sported worn-out robes, was paler and way more dreadful.

The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

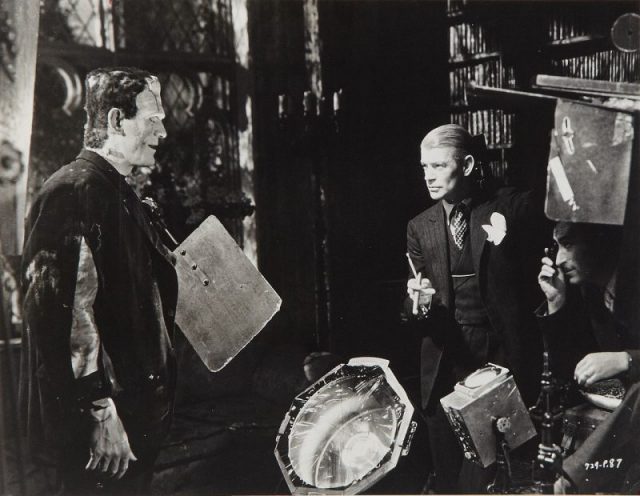

Lon Chaney was well-noted for his abilities to morph his human face into a monstrous one using his very own makeup box and ingenious creativity.

In 1925 he did that for the eerie lead character in The Phantom of the Opera. Two years before that he had perfectly embodied Quasimodo.

To achieve his Phantom looks, Chaney used some unusual substances. For his skull he used cotton. But for his prominent cheekbones, he used collodion — a colorless substance that helped photographers in the 19th century develop some of the first high-quality negatives.

Fish skin and wire is what helped the actor obtain a tilted nose. He also wore dark eyeliner and false serrated teeth.

It wasn’t a comfortable mask at all, but Chaney coped with it. Besides that, there was his skillfulness as an actor, his ability to deliver a believable character in the 1925 silent horror that would send chills down the spine of everyone.

“Chaney’s performance absolutely terrified his audiences. Moviegoers regularly fainted and stifled screams,” wrote The Los Angeles Times.

The Wolf Man (1941)

Long before Remus Lupin was bitten as a young lad by werewolf Fenrir Greyback in the Harry Potter series, the character of Mr. Talbot suffered a similar fate in the 1941 adaptation of The Wolf Man. It was the first horror film featuring a werewolf character that became a box office success.

It was a fierce contest of who gets to play Lawrence “Larry” Talbot who eventually becomes the notorious Wolf Man. Both Bela Lugosi and Lon Chaney Jr. wanted it. In the end, the part was given to Chaney and Lugosi was cast as the werewolf who bites Mr. Talbot in the movie.

Chaney had to sit for hours without making any movements as each werewolf scene was carefully crafted, frame after frame. He sometimes needed to sit out lunch breaks on the set and skip going to the bathroom in order not to ruin his look, which consisted of a lot of yak hair glued in layers, wigs, and other props applied face-to-feet to achieve the image.

It took up to six hours to make him look like a proper werewolf and an extra hour after filming to take off of all the makeup and props. This was a pain to Chaney who complained about it at the time.

The 1980s revamped the werewolf character. American Werewolf in London used advanced visual effects, allowing a way more visceral human-to-monster transformation.

King Kong (1933)

Eight decades before Peter Jackson had his take on King Kong, the story of the gargantuan gorilla who kidnaps a beautiful young lady was directed and produced by two friends who had initially planned to make a documentary about the apes.

Nevertheless, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack ended up devising a plot about the scariest among them all. Willis H. O’Brien, who had formerly created dinosaurs for the 1925 film The Lost World, was hired to use his magic and animate the freaky gorilla.

O’Brien exploited his stop-motion skills and an 18-inch prop of King Kong to bring the monster to life on screen.

Movie critics in 1933 remarked that some of the Kong movements do look a bit mechanical and there are flaws in the production, yet as the Times writes: “It took cinematic ambitions as big as Kong himself to make the picture, which required immense resources and the most cutting-edge special effects then available.”

Godzilla (1954)

The idea of having such a distasteful monster as Godzilla in cinema was conceived by abhorrent real life events.

In 1954, the U.S. was carrying out thermonuclear weapons testing on Bikini Atoll. A tide of radiation fallout contaminated a fishing vessel called Lucky Dragon 5, whose crew suffered from acute radiation syndrome. The scandal shocked Japan.

This is how the film begins. A Japanese vessel close to Odo Island is confronted, not by a nuclear weapon, but by its fictitious monstrous counterpart the size of a skyscraper.

“Rarely has the open wound of widespread devastation been transposed to celluloid with greater visceral impact,” would note Slant Magazine‘s Budd Wilkins in a review.

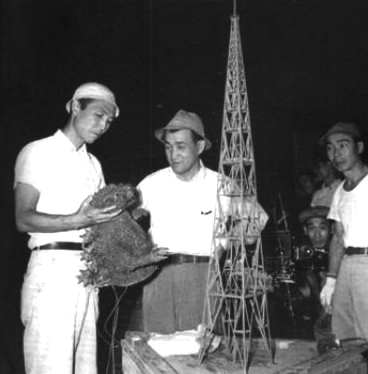

The film, directed by Ishiro Honda, hired Eiji Tsuburaya for its special effects. The monster was supposed to be a giant octopus at first, but Tsuburaya and the team opted out for something more dinosaur-like.

Tsuburaya used a special latex costume for the movie’s ghastly creature and a special filming technique that embraced double-speed shooting on set and slowing those scenes back in the studio. Such an approach was later mocked by critics, but at the time proved to have a terrifying effect on Japanese audiences.

Gremlins (1984)

Everyone remembers the cute little creature named Gizmo who was scared of getting wet and would die if exposed on the sun. And the consequences when Billy fails to stick to the three simple rules that come with his mysterious new pet.

The script was originally written by Chris Columbus and in it, the Gremlins were way darker than they ended up on-screen. Gizmo was supposed to morph into Stripe, for instance.

Despite the sugar coating, director Joe Dante was still criticized at the end. One mother told him “the scene where a gremlin explodes in a microwave was totally unsuitable for kids,” the Guardian reports.

The inspiration for Gremlins came from the mice that shared Columbus’ Manhattan apartment during his student days, especially during nighttime when he found their presence “really creepy.”

On the silver screen, the Gremlins were much more than mice and it took a great deal of special effects to bring them to life. Beside visual effects, a key was the voicing of these nightly demons.

Canadian comedian Howie Mandel was cast as the voice of Gizmo. His voice was sped up a bit with sound editing. “Howie’s performance was a major part of making the creature credible,” director Dante told the Guardian. A young girl further supported the Gizmo character with her singing talents.

Stripe was voiced by actor Frank Welker who had previously breathed life into Scooby-Doo’s Fred.

Read another story from us: Dazzling Poster for 1932’s ‘The Mummy’ Set to Break Records at Auction

Gremlins remains an iconic comedy horror which freaked audiences in 1984 and has been a Halloween favorite ever since.