Catholics around the world hold the saints in veneration, among them being that of Joan of Arc. For centuries, churches and cathedrals across Europe drew power, prestige, and patronage with their collections of holy relics. Those relics were often bits of the remains of a saint or saints.

Joan of Arc

Different people feel drawn to different saints for personal reasons, and sometimes an area or region might hold a special affection for a particular saint who came from that place. In France, many people have such a reverence for Joan of Arc. At only 18, Joan led the French army to victory over the English at Orléans.

Joan claimed that she was guided by mystical visions of the saints, who told her she was meant to be France’s savior, and she was operating under divine guidance. While many believed her at first, a year later in 1431, she was burned as a heretic and a witch. Today, she is regarded as a figure of veneration and inspiration among French Catholics.

Her ashes

In 1867, in the attic of Paris apothecary, the ashes from the foot of St. Joan’s pyre were discovered. They were in a jar with a label that said “remains found under the stake of Joan of Arc, Virgin of Orleans.” Following its discovery, the jar was taken to a museum and kept there for decades. However, in 2007, analysis of the artifact revealed that the ashes in the jar were not, in fact, from the saint after all.

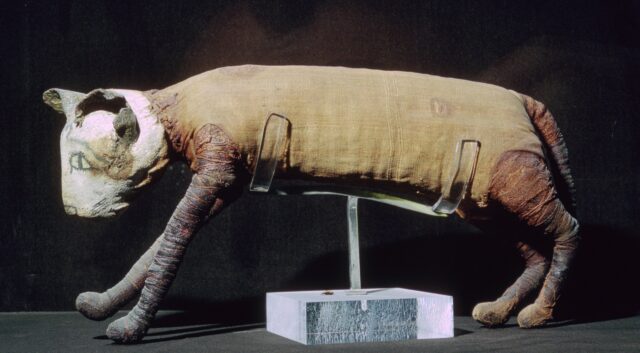

Instead of belonging to the 15th century patron saint, they were dated to sometime between the sixth and third centuries BC. Dr. Philippe Charlier of the Raymond Poincare Hospital studied the relic and was amazed by what he found. The ashes included a burnt, seemingly human rib, some charred lumps of wood, a six-inch scrap of linen, and the femur of a cat. (There was a medieval tradition of throwing black cats onto the pyres of witches.)

Charlier and his team performed a variety of tests on the relic, and the evidence of those tests began to suggest that it was not from Joan of Arc’s pyre, but rather from a mummy.

Why would the jar be mislabelled?

Their best guess is that the fake was concocted sometime in the 19th century, maybe to help move along Joan’s beatification process. This may hold some merit, as she wasn’t canonized by the Roman Catholic Church until 1920. Why the jar was found at an apothecary also suggests that the remains are that of a mummy.

In medieval times, powdered mummy remains were put to use in various medications. They were used to treat all manner of blood problems, long or painful periods, and complaints of the stomach, according to Dr. Charlier. His team assumes that the apothecary transformed the mummy remains into a fake relic of Joan of Arc, but why he would have done so is a mystery.

Details about the true identity of the ashes

Not only was the rib bone from centuries ago, but so was the cat femur, which had also been mummified. Additionally, the research team found evidence of pine pollen, which could be from the resin used in Egyptian embalming techniques.

The team wasn’t able to get any usable DNA from either the human bone or from the one belonging to the cat, so the sex of the mummy can’t be identified, nor can the sex of the cat. Charlier said, “the embalming products appear to have prevented the conservation of the DNA, and they are too old, so it didn’t work.”

They even called in perfumers to help them in their research, to sniff the remains and help identify any scents that could help identify the vegetable matter used in the embalming. After doing so, the perfumers identified scents of plaster and vanilla. While the smell of plaster could be consistent with her being burned at a plaster stake, rather than a wooden one, in order to prolong the spectacle of her execution, the vanilla shouldn’t have been there.

Vanillin is produced by a decomposing body, according to Charlier. You would find it in a mummy but not in a body which had been burnt. That was how the team began to figure out what they were looking at.

The period the discovery of the relics occurred – the 19th century – was the same period during which the nearly-forgotten Saint Joan of Arc was being rediscovered by the French and made into a national icon. So, the idea that someone may have forged her relics to promote her importance isn’t terribly hard to imagine.