In the great dynasties of China there are many tales of corruption, espionage, and intrigue, but perhaps no tale is more intriguing than the rise of China’s first and only woman Emperor, Wu Zetian.

In the hierarchies of Imperial China, there are many who call themselves empress, and there are many who held sway over their weak-minded emperor husbands, but only Wu Zetian reached the pinnacle when at the age of 65 she usurped her son and became the undisputed Empress of Tang Dynasty China.

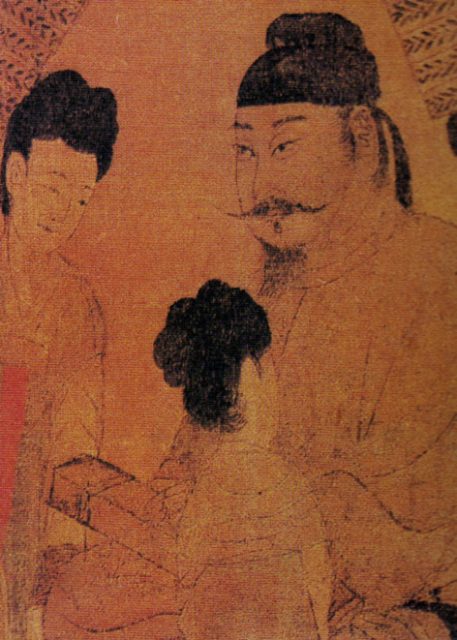

Wu Zetian’s rise to power began at age 14, when Emperor Taizong took her to the Forbidden City to become one of his concubines.

Although only a tier five concubine, essentially a maid, she soon impressed the Emperor with her intellect and beauty and rose to the rank of secretary, a position that gave her access to the courts and started her education in politics.

It didn’t take long for Wu to become Taizong’s chief imperial concubine and his most trusted advisor. Being a tenacious type she also began an affair with the heir to the throne, Li Zhi.

It was common practice in the Tang dynasty that when the Emperor passed away, the concubines of his court would be sent to a temple to live out their lives in caste religious reflection.

Such a fate awaited Wu when Taizong died but Li Zhi, now Emperor Gaozong, had fallen deeply in love with her and — against the rules of the court — he brought Wu Zetian back to the palace and made her his main concubine.

Standing in the way of Wu and the Empress chair were two women: Lady Wang, Gaozong’s wife and a woman known only as the Pure Concubine, who may or may not have been Lady Wang’s mother.

Lady Wang had not been able to produce any children with the Emperor, but Wu Zetian had given birth to two sons and a daughter.

The story goes that Wu smothered her own daughter, the youngest child, and placed the blame on Lady Wang.

The Emperor, overcome with grief, believed Wu Zetian and had Lady Wang banished from court along with her supposed accomplice, the Pure Concubine.

When Wu was firmly instated as Empress Consort, she had the feet and hands of both her rivals removed and their bodies thrown into vats of wine to drown.

At first, Wu presented herself as the traditional, devoted wife but it was soon clear to everyone that Wu was in control of the decision making.

Much to the chagrin of the traditional Confucian courtiers, Wu would attend religious ceremonies previously only attended by men and had the empress’ throne raised to the same elevation as the emperor’s.

When Gaozong was taken ill, which he often was, Wu would hold court in his place, and when he suffered a crippling stroke, she took over administrative duties, effectively ruling as emperor.

After the death of Gaozong, Wu installed her eldest son as emperor, but when he proved too arrogant, she accused him of treason and had him banished.

Wu then installed her second son; when he proved too weak, she forced him to abdicate in her favor.

For the next fifteen years, Wu Zetian ruled as empress, maintaining her power through a highly effective and often violent network of secret police, spies, and murder.

What we know about Wu Zetian is colored through the lens of history and as the most powerful woman in China she definitely upset a lot of people, namely men, so whether she did commit all the crimes leveled against her, we will never know.

According to some sources, Wu was responsible for the complete destruction of fifteen family lines over the space of one year, forcing many of her enemies to commit suicide in front of her, and she kept her own harem of young men well into her eighties.

Although undoubtedly ruthless, Wu oversaw policies that made her popular among her subjects and led to a period of prosperity across the empire.

Among other things, she opened up palace grounds to farming and created a minister for agriculture to ensure proper field management, she reformed the education system so that women and girls could get an education, and she removed hereditary job entitlements filling the government instead with capable advisers based on their skills and abilities.

This last change almost singularly wiped out corruption on a national level and had the bonus of removing many of Wu’s enemies from court.

Read another story from us: 6 Cleopatra Myths Debunked

Wu was finally forced to abdicate in 705 AD in favor of her eldest son who she had banished years earlier. By this time Wu was an octogenarian. She was banished to a countryside palace where she died peacefully one year later.