The Battle of Gettysburg was a long, brutal battle with the largest casualty count of any engagement fought during the American Civil War. It also marked the conflict’s turning point, allowing the Union Army to begin getting the upper hand over Gen. Robert E. Lee‘s Confederate forces.

The battle lasted three days – from July 1-3, 1863 – and only ended after Pickett’s Charge went disastrously awry, resulting in the loss of over 50 percent of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s forces. Although Lee won other victories, he never really recovered from the devastation at Gettysburg.

How to observe the Battle of Gettysburg’s 50th anniversary

In April 1908, a general from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania who’d been wounded at Gettysburg and lost an arm suggested a way to mark the observance of the 50th anniversary of the battle. He mentioned his idea to then-Gov. Edwin Stuart, who presented it to the state’s General Assembly the following January, establishing the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg Commission later that year.

The idea was to hold a reunion on the Gettysburg Battlefield for both Union and Confederate veterans who’d fought there. There had been other reunions there before, but this one would be much bigger. The commission sent invitations to all surviving Civil War veterans, calling on the government to help fund transportation to those living in other states.

The commission helped Gettysburg get ready for the 100,000 or so guests that they expected would be arriving (half of them veterans) and staying for the event.

Getting Gettysburg ready for the big day

The arrangements and planning for what became known as the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion were complicated. The expense of finding and transporting so many veterans, some from as far away as California, was more than many states could bear. A few passed legislation to help fund the trips, but many were forced to rely on personal donations.

Even so, the burden being put on the state of Pennsylvania continued to grow, and the plan couldn’t have come to fruition without help from the federal government.

The camp for the veterans opened on June 29. It was enormous (about 280 acres), with room for over 5,000 tents, arranged by state. Artesian wells were installed, and each tent was equipped with two basins and a water bucket. The commission reported that over 53,400 veterans were housed in the makeshift lodgings.

The War Department assigned nearly 1,500 military personnel to help things go smoothly. Other occupants of the village included some 155 journalists and over 2,100 cooks.

1913 Gettysburg Reunion

Various public exercises took place under an enormous tent each day of the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion, including a reading of Abraham Lincoln’s famous address, speeches, the dedication of state monuments and a fireworks display. President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech on July 4.

When the men weren’t participating in these, they had ample opportunity to have mini-reunions, catching up with old friends and having a chance to get to know old foes. There were many instances of veterans looking for someone who’d shot them during the battle or to exchange badges. Two men even went so far as to purchase a hatchet at a local hardware store and symbolically bury it in the ground where the battle had been fought.

A most interesting occurrence happened when a Confederate soldier told his story to a Union veteran of having been saved by a Union serviceman after being shot. The latter then said he’d done that same thing for a Confederate soldier during the battle. He then went on to explain his actions.

The Confederate soldier listened and replied that that was what had been done for him. After looking the other man over, he was reported as saying, “But, my God, that’s just what the Yankee did for me. There couldn’t have been two cases like that at the same time. You are the man.”

Now, for some photos from the historic reunion…

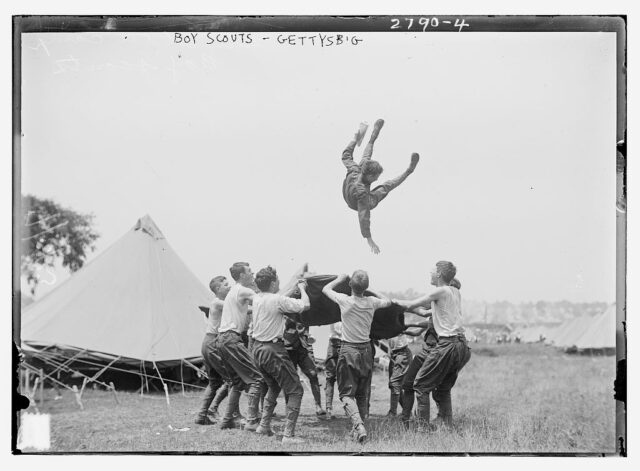

Boy Scouts having a good time

The Boy Scouts were among those brought in to help ensure the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion ran smoothly. Here, you can see them having some fun during their downtime.

Taking the time to eat

The tent these men are standing under appears to have been used as a makeshift kitchen on the battlefield. We can only imagine the manpower it took to feed all the veterans who traveled to Gettysburg.

Catching up

As aforementioned, the majority of the veterans who attended the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion spent time catching up with former comrades and getting to know the soldiers who fought on the opposing side.

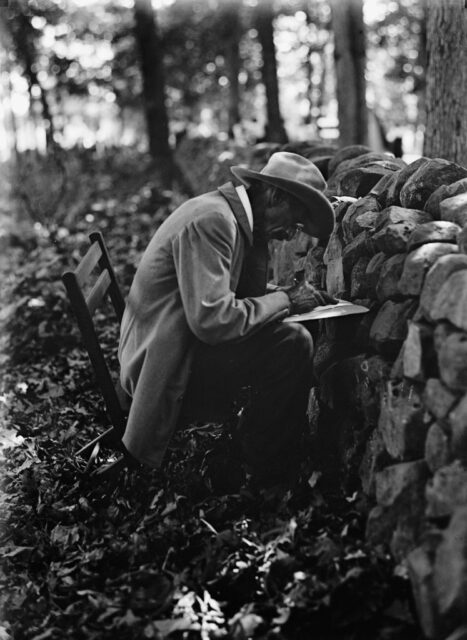

Taking some time for oneself

Amid the busyness of the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion, some men took the time to enjoy the peace and quiet of their own company, writing down their thoughts and experiences of the historic event.

Arriving at the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion

For those attending the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion from out of state, the primary mode of transportation was train, with many crowding aboard locomotives to attend the historic event.

Hundreds of tents

As aforementioned, hundreds of tents were erected to house the tens of thousands of veterans who made their way to Gettysburg for the reunion. They were modest lodgings, but the majority didn’t care – they weren’t there on vacation.

Playing some music

What’s a gathering without music?! As this photo shows, many of those who were musically inclined shared their skills with other attendees, providing entertainment outside of the scheduled exercises and activities.

Meal time

A jam-packed schedule meant there were many hungry stomaches to feed by meal time, and by the looks of this line, many were eager to grab a plate.

Tents and horses

In the 1910s, cars still weren’t a common sight on the roads, as they came at a hefty price tag. As such, horses were a common sight at the 1913 Gettysburg Reunion, as they were part of the transportation used to get the veterans there.

72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

More from us: The Tragic Off-Camera Lives of the Cast of ‘Gilligan’s Island’

The 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment was a volunteer regiment that served as part of the Union Army during the Civil War. They took part in several battles – Ball’s Bluff, Gettysburg, Antietam, etc. – and suffered a 65 percent casualty rate. In their honor, a monument was erected on the Gettysburg battlefield.