The Second World War brought with it a surge of interest and development in the field of cryptography. It proved vital in many aspects of the conflict to have safe channels of communication, as surprise was key in organizing offensives, which would often involve hundreds of thousands of people. While writing the codes was an unprecedented effort, both sides also worked tirelessly to intercept and decipher their enemy’s ones to gain the upper hand.

Developing an unbreakable code

When the United States entered the war in the Pacific Theater, its forces were met with several issues. One was that the English language proved unsafe for use in codes. Most Japanese cryptographers were educated in America and were prepared for code-cracking once the conflict escalated, easily intercepting and decoding the US military’s radio-transmitted orders and messages.

While figuring out an alternative, the US Marine Corps received a proposition from civil engineer and veteran Philip Johnston, who claimed to have a solution. He was a son of missionaries who grew up with the Navajo in Arizona, becoming one of the few outsiders who spoke their language. Thus, when World War II broke out, he came up with the idea of using the Navajo language in code, as it was largely unknown to anyone outside of the reservations.

After a successful demonstration, during which four Navajo dockworkers participated as “Code Talkers,” the idea was put forward for consideration.

Bringing back memories of the First World War

This wasn’t the first time the United States turned to Native Americans for help with coded messages. During the final months of World War I, it was common practice for soldiers of Cherokee and Choctaw origin to translate messages of high importance into their native tongue to preserve their secrecy.

The need arose in mid-1918, when the 30th Infantry Division realized the messages being sent by the American forces weren’t as secure as they’d assumed. This prompted a group of Eastern Band Cherokee troops to use their Native language to take control of communications for the 105th Field Artillery Battalion.

This proved effective, with the Germans unable to decipher what was being said, cementing a need for such troops in the US military. Other notable Code Talker groups served with the 142nd and 143rd Infantry Regiments, proving effective during the Second Battle of the Somme and other assaults.

Developing the code

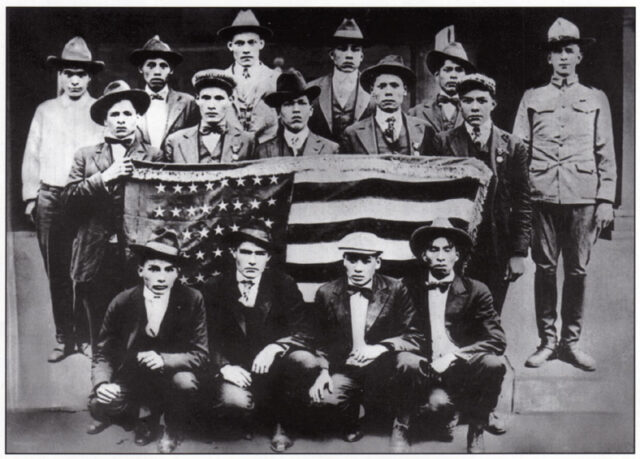

The success of the demonstration led to the recruitment of 200 Navajo men into the US Marine Corps and their subsequent training in the field of cryptography. Chester Nez was among the first to enlist in the experimental unit of 29 responsible for establishing the code using Navajo words.

The group, known as Platoon 382, used a coded version of their language, which meant that, unless someone was a member, they couldn’t understand what was being transmitted, even if they spoke Navajo or had access to a training manual. The code that was developed allowed the Code Talkers to translate three lines of English in just 20 seconds – faster than existing machines that took upwards of half an hour to do the same task.

The language itself had very few military terms, which meant that suitable replacements needed to be used to transmit precise messages and avoid misunderstandings. For example, a submarine was referred to as a “metal fish,” while dive bombers were called “chickenhawks.” Furthermore, new words were devised for verbs, such as capture, escape, entrench, flank, halt and target.

Navajo Code Talkers

Throughout the Second World War, 420 Navajo men were recruited (some sources say 540), as the code had proved successful beyond anyone’s imagination. In fact, it became the only oral military code to never be broken. Most of the time, they were split into pairs and assigned to units, with the idea being that one could operate the radio while the other relayed/received messages that they then translated into English.

Participating in all major campaigns from 1942-45, the Navajo Code Talkers developed a complex system of ciphers that provided the US Marine Corps the edge it needed to achieve victories against the Japanese. This proved especially true during the Battle of Iwo Jima, when the men transmitted over 800 messages, prompting Maj. Howard Connor of the 5th Marine Division to later say, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

Chester Nez, who was raised in Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools, was surprised to learn that the language, suppressed during his education, now took a central role in the fight for the future of the United States. In 2002, he recalled his experiences in an interview with USA Today, saying, “All those years, telling you not to speak Navajo, and then to turn around and ask us for help with that same language… It still kind of bothers me.”

Not immune to prejudice

Although the role of the Navajo Code Talkers proved pivotal, they still suffered discrimination on the home front. After the war, they were obliged to keep silent about their actions, as the code was categorized as top secret. This meant they couldn’t inform their families of their bravery.

Until 1968, the Navajo Code Talkers weren’t allowed to mention their contribution to the war effort and were largely neglected as veterans. It wasn’t until 2001 that they were recognized with the Congressional Gold Medal.

More from us: Shiro Ishii: The Architect of Japan’s Horrific WWII Experiments That Left Thousands Dead

Their efforts are, today, fully recognized, and the significance of the code they created remains engraved in history as one of the most important factors that ensured the Allied victory in the Pacific.