A “border pillar” shoved into the ground some 4,500 years ago in what is now southern Iraq underscores the fact that disputes over territory are as old as civilization itself.

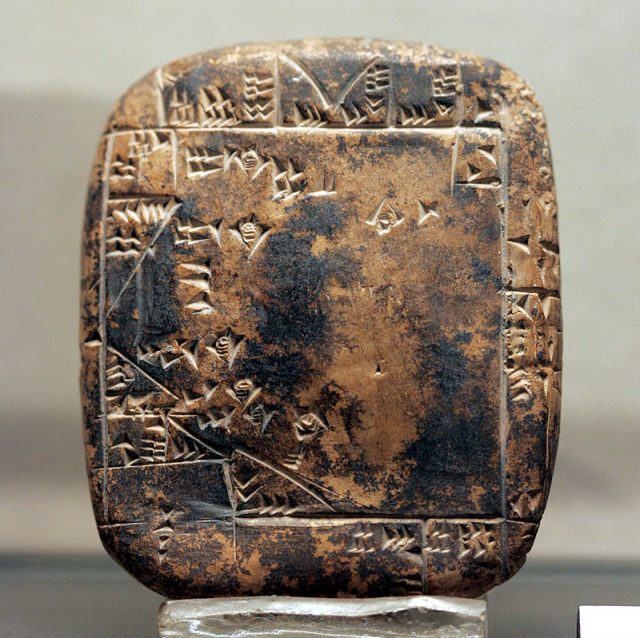

For 150 years, the British Museum’s collection has included the Lagash Border Pillar, a stone white pillar that King Enmetena of Lagash had erected to mark his territory in 2400 BC “and its glistening surface would have shone out brightly and assertively under the sun beating down on the plain.”

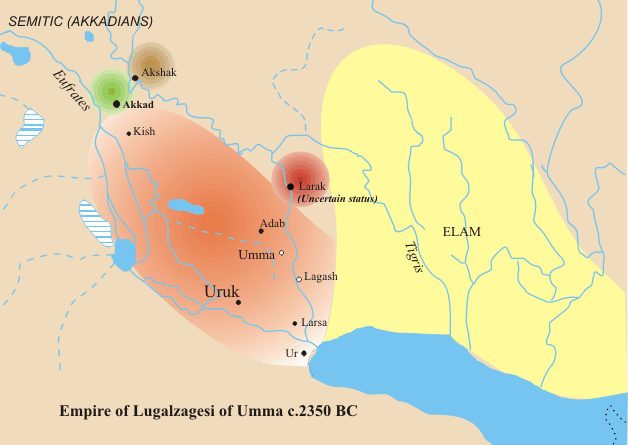

Recently the inscription on the pillar was translated, and its aggressive language showed the struggle to create a “no man’s land” between the kingdoms of Umma and Lagash in Mesopotamia

According to the Smithsonian, “The fight between Umma and Lagash is one of the oldest known wars in human history and led to what may be the world’s first peace treaty and one of the oldest legal documents, the Treaty of Mesilim, signed around 2550 B.C. The treaty set up a border that was demarcated with a stele along an irrigation canal, similar to the one on view in the museum.”

It is the focus of a new exhibit at the British Museum called “No Man’s Land.” Wrote The Financial Times: “No Man’s Land is the latest in a series of tightly focused displays staged in the single-room space that lies immediately to your right as you pass through the museum’s portico.”

The translation on the pillar includes dire warnings (in cuneiform) for anyone who dares step over the boundary. The translation seems to warn that if the gods don’t stomp on you, poisonous snakes will finish you off.

Over 4500 years ago, Lagash, and Umma, neighboring states, fought bitterly over a fertile tract of land called Gu’edina, “Edge of the Plain.”

“The ancient objects showcased here document the perspectives of the opposing sides, with both territories invoking divine sanction and precedent to justify their claim over the land,” the museum says.

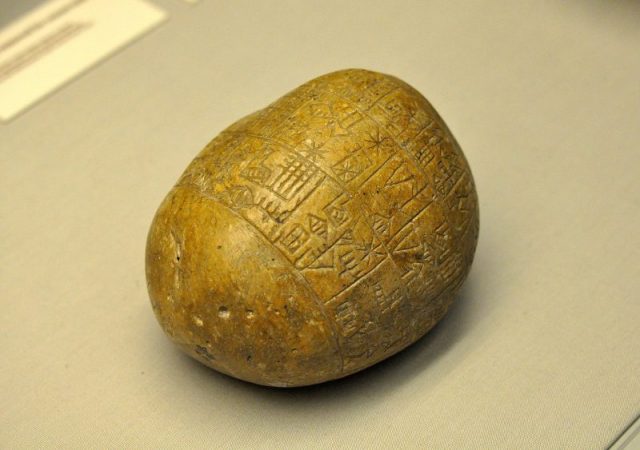

Alongside the stone pillar in the British Museum stands the Umma Mace-Head that was made for King Gishakidu of Umma, who was Enmetena’s enemy and his contemporary. “Long regarded as a vase, it is now understood that this is a symbolic mace-head which has always been displayed upside down — until now,” the museum says.

On top of the mace-head is a black painted representation of the battle net that was used by the gods to immobilize enemies for execution. The Ur Plaque also on display in this show illustrates a tradition followed by Lagash and Umma in which offerings were made at the border shrine under the protective eye of the Moon God.

The Smithsonian says, “This wasn’t just a roadside sign marking Lagash’s territory. It is a heavily inscribed object, telling the complete story of the war between the two cities over the land. It also includes what may be the earliest-known example of written word play.”

“Whoever chiseled the pillar didn’t just take pains to emphasize the name of the Lagash god Ningirsu, substituting some of the cuneiform marks in the name with the symbol for god, they also threw some shade on the rival god of Umma, writing the god’s name in a messy, almost illegible script.”

Irving Finkel, a curator in the Middle East department who deciphered the Sumerian cuneiform writing, told The Financial Times, “You have in one breath the use of writing in a magical way to enhance the power of one deity and then nullify the power of the other. This is unique in cuneiform. It’s the most exciting thing you can imagine.”

Read another story from us: 4,000-yr-old Tablet is the World’s Oldest Customer Service Complaint

The museum display, No Man’s Land, “brings to light the fragility of borders throughout history. The ancient and contemporary works exhibited address the issues around the human desire to dominate land, and allude to the brutality and turmoil borders have invoked on those that inhabit them as well as the landscape itself,” says the British Museum.