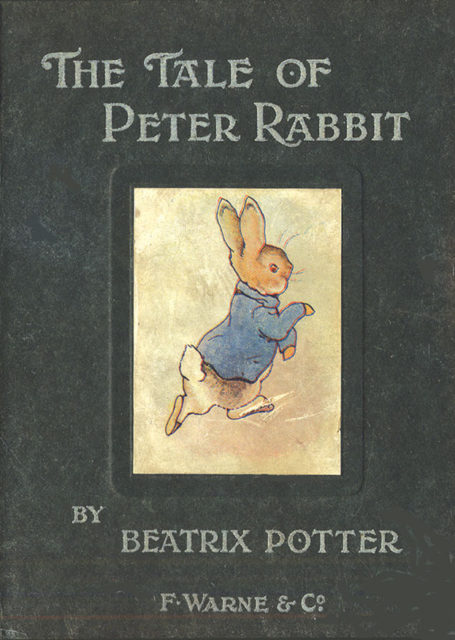

Beatrix Potter is best known for her heartwarming illustrated children’s stories, set in the pastoral idyll of the English countryside. Characters such as Peter Rabbit, Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle and Jemima Puddle Duck have continued to delight generations of children over the past 100 years, making Potter into a literary sensation.

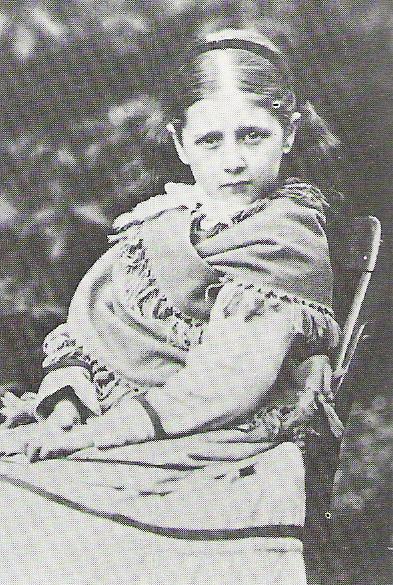

However, few people realize that Potter kept a secret, coded journal in her youth. This epic collection of observations, poems and notes is a fascinating reflection of the author as a young woman, and offers a powerful insight into the world in which she lived.

July 28, 1866.

Moreover, if it wasn’t for the dedication and tireless labor of one Potter super-fan, this priceless collection, said to be her masterwork, might have been lost to history forever.

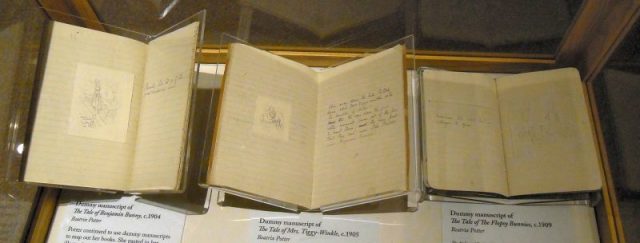

According to the BBC, Potter’s diaries were discovered in her house several years after her death, by Stephanie Duke, a young relation. To the untrained eye, they represented little more than a series of tightly wound scribbles on the page, apparently meaningless, or certainly impossible to decipher.

Potter had left no instruction for the papers, nor had she provided a cipher for translation. In fact, some years before her death, she had written to a friend dismissing her early diaries as “exasperating and absurd compositions.”

However, Duke was eager to discover the contents of the papers, and she decided to consult one of Potter’s biggest fans. Leslie Linder had fallen in love with Potter’s creations as a child, and in his later life, he set about buying up as much of her work as he possibly could.

According to biographer Andrew Wiltshire, Linder jumped at the chance to decipher Potter’s papers. Although the code did not appear to be particularly complex, Potter’s miniscule writing meant that the text was almost impossible to decipher.

She would often squeeze thousands of words onto a single page, and appeared to have written in a disorganized, haphazard fashion, using any papers she had to hand. Some passages were even scribbled in the margins of a French dictation book.

Linder struggled to understand anything in the pages for at least five years. Then, one day as he scoured one particular notebook, he found a clue. Piecing together the Roman numerals XVI and the date 1793, he realized that the passage appeared to be a reference to the French king Louis XVI, guillotined in 1793.

He deciphered the word ‘execution’, and using this, was able to finally crack the code that Potter had developed. However, although Linder finally understood the code, it still took him many more years to decipher the rest of the papers.

According to Wiltshire, in total, Linder worked on Potter’s collection for 13 years, patiently translating her words and painstakingly researching the events that she recorded.

Linder’s tireless work revealed an entirely new face to Potter and her life as a young woman. Her notes were filled with references to animals and the outside world, and express her frustration with the prim, urban lifestyle she was born into.

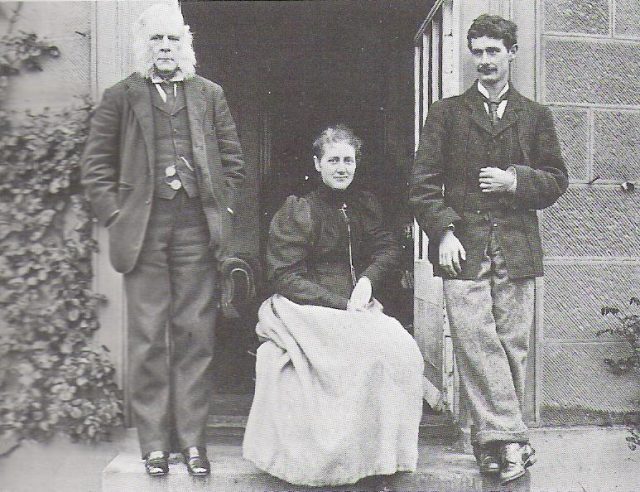

Her parents wished her to live as a genteel young lady, whereas Potter had other ideas. She was intelligent and inquisitive, and above all expressed a passion for the natural world. Her journals were a space where she could rail against the tight strictures of Victorian life.

Her future as an artist and writer is prefigured in the papers, which contain many references to her drawing and painting, as well as a number of pointed and brutal art reviews.

The coded journals provided a space where the young Potter could feel free to express herself, and they therefore represent a wonderfully unguarded reflection of her inner thoughts and opinions.

Linder’s tireless work in translating Potter’s papers has provided an invaluable service for historians. They have brought to life the image of Potter as a young woman, demonstrating her to be much more than a simple country farmer with a taste for whimsical stories.

She is revealed, through her private papers, to be an intelligent and acerbic social commentator.

Read another story from us: Alcohol Inspiration: The Drinking Habits of 8 Famous Writers

Her insights can tell us much about social and cultural life at the turn the of the 20th century, as well as shedding light on the character of this important and much-loved British author.