Workers’ strikes are a common way to push employers to pay fair wages with adequate benefits. When workers stop participating in work, everything grinds to a halt, putting pressure on those who own the means of production to improve working conditions and/or increase pay.

The history of work strikes has been recorded as early as the 12th century BC in ancient Egypt, during the ruling of then-Pharaoh Ramesses III, roughly around 1170 BCE. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Base, a damaged and incomplete papyrus was found, which stated that the artisans and tomb workers tasked with building his necropolis repeatedly went on strike over poor rations.

While it’s unclear why they didn’t receive their rations, there’s some evidence that a food shortage was the result of corruption stemming from within the ruling class.

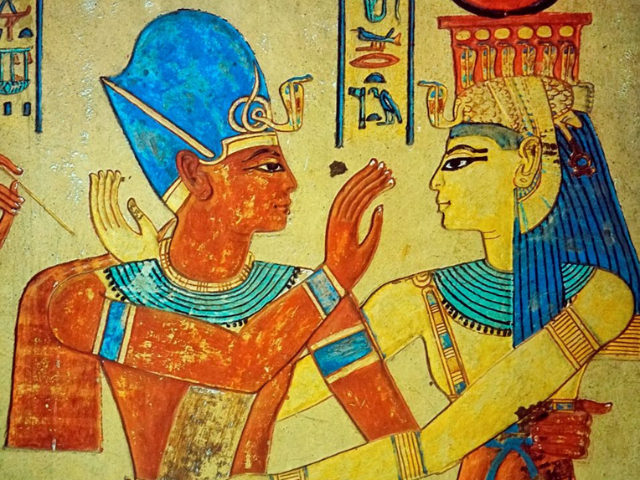

Ramesses III

Ramesses III inherited the title of pharaoh around 1186 BC as the second pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty and asserted his rule by protecting the boards of Egypt from the ruling powers in the region. Over the course of his rule, temples and monuments were restored, likely to boost his people’s morale. He was considered to be the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom, paying tribute to Ramesses II by continuing to be a great king and a father to his followers.

Even with all he was able to accomplish during the early stages of his time as pharaoh, the kingdom lacked its previous status as a supreme power. This was due, in part, to the economic turbulence that began during the reign of his predecessor, Setnakhte. On top of those pressures, the kingdom was suffering from a reduction in trade and tribute, which lessened the resources available.

Ramesses III was assassinated during the Harem Conspiracy, a coup d’etat orchestrated by his second wife, Tiye, who’d hoped to install her son, Pentawer, on the throne. While those involved were successful in killing the reigning pharaoh, they weren’t able to accomplish the second part of their mission, with Ramesses IV, the son of Ramesses III, gaining control of the kingdom.

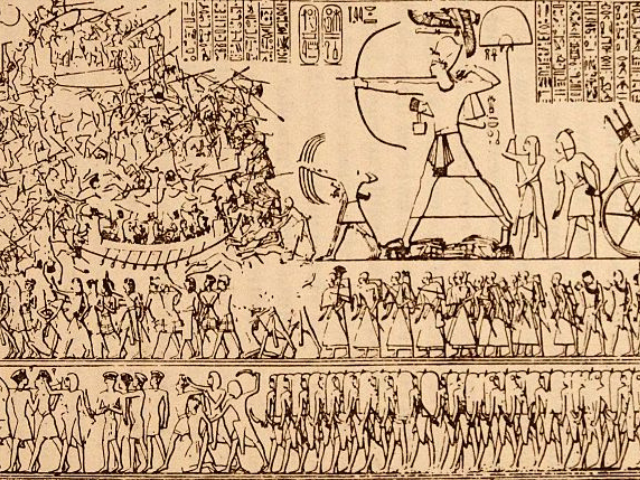

Invasion by the Sea Peoples

Ramesses III reigned over a relatively peaceful Egypt until an invasion by the “Sea Peoples,” mercenaries and raiding types from the Mediterranean, depleted both funds and laborers who’d normally have worked the fields to produce much-needed resources. No one knows what nationality they were or if several were represented, and experts continue to debate the suggestion that they could’ve originated from western Anatolia, the Aegean, the Mediterranean islands and southern Europe.

According to World History Encyclopedia, the Sea Peoples were struggling to reach land during the attack, since Ramesses III had directed his generals to establish strongholds across the borders, while also deploying navy ships. One of his tactics was to hide archers along the coastlines near the mouth of the Nile to prevent the boats from even entering the river.

His tactics were recorded to be a major success on the seafront, but nothing was mentioned in the inscriptions about the land battle, likely due to the high number of casualties that weren’t officially recorded.

Peacetime plagued by corruption

The next few years were peaceful within the New Kingdom, which allowed Ramesses III to begin work on many temples. He and his entourage also took a grand tour of Egypt, further depleting the coffers, and he ordered expeditions to nearby foreign lands to establish trade and military conquests, which were successful. Although these conquests should have been more than sufficient for replenishing the treasury, they still weren’t enough.

There are several factors that could explain what happened, but scholars offer theories that include central problems, including a large loss of labor from the war, high expenses incurred in fighting off the Sea Peoples, corrupt officials misplacing resources and a harsh harvest due to unfavorable weather conditions.

Regardless, those issues further contributed to the resource shortage, putting workers in a tough position where they had to resort to going on strike. Their job action wound up spanning years.

Great celebrations during bad times

In the meantime, Ramesses III decided there’d be a great celebration in honor of the 30th year of his reign. He and his advisors had no idea how to deal with the hungry workers, as this sort of thing had never happened before. At one point, officials gave the workers pastries, and while they did take them and enjoy drinks during the celebrations, they resumed their strike the next day, and it continued for months.

Since the workers from Deir el-Medina were some of the highest paid in the country, their poor treatment represented instability for those worse off. Eventually, as a last-ditch effort, officials were able to make payments to them on time, but their relationship was never the same, since they saw Ma’at – the concept of harmony – as the responsibility of their king and father.

More from us: 11 Unbelievable Hygiene Practices From Ancient Egypt

This was, however, the beginning of the decline of the pharaoh’s power and his subject’s blind devotion. It was also the start of a dispute solution instigated by workers that made them assume the responsibilities of the king.