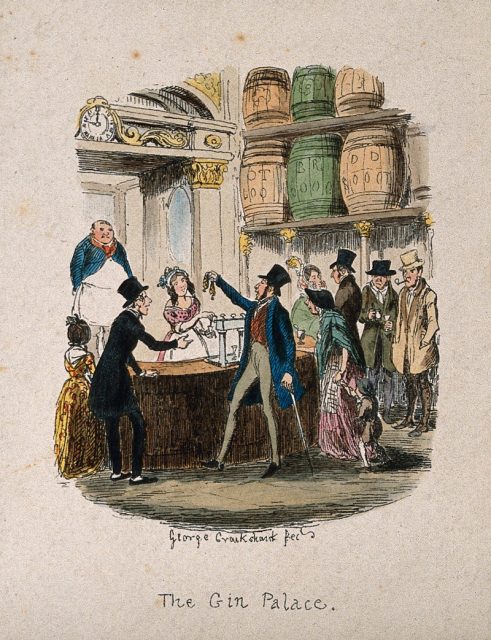

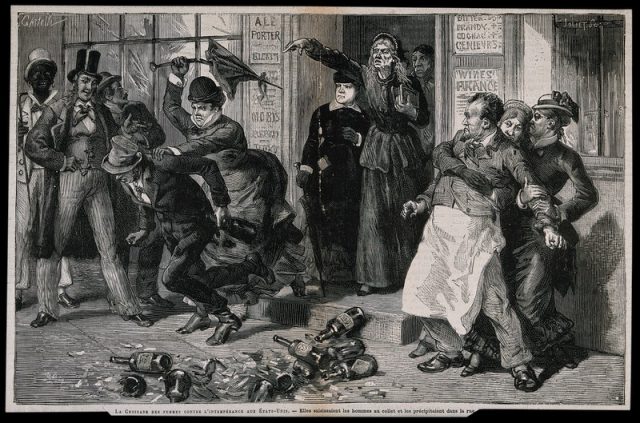

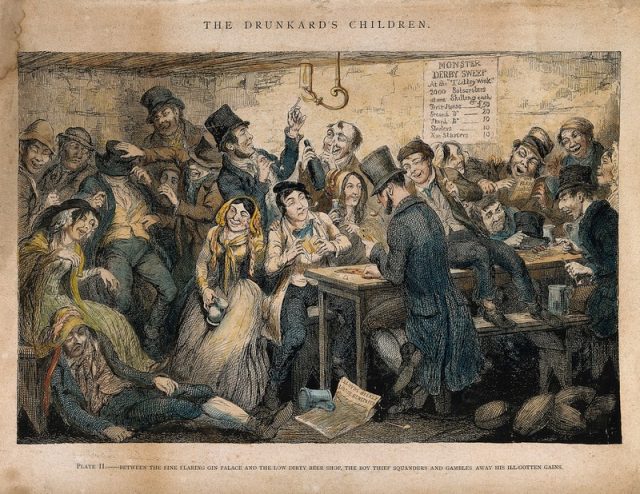

The 19th century was an era of tremendous moral panic about the consumption and effects of alcohol. The temperance movement, which campaigned for total abstinence from the “demon drink,” became widespread in North America and Britain the 1820s, but as early as the 1750s the morally superior had fretted and tutted about the drunkenness of the urban poor in places like London.

However, even those fond of a good drink had good reason to fear for the health and sanity of the hard-drinking man or woman in the street. Sometimes their gin, brandy, rum or beer was laced with Cocculus indicus, the berry of a South East Asian climbing plant, along with other commercially available poisons.

Cocculus indicus is a source of picrotoxin, a plant compound with potentially deadly side effects, described by the Victorian toxicologist Alfred Swaine Taylor in 1843 as “nausea, vomiting, and griping pains, followed by stupor and intoxication.”

It was traditionally used in Asia to stun fish for hunting, and soon proved popular with British publicans (pub owners) who used Cocculus indicus berries to introduce “giddiness” and disguise the fact that the beer was watered down to increase the their profits.

For good measure they often added salt to make the patrons even thirstier.

Taylor wrote: “The fraud is perpetrated by a low class of publicans. They reduce the strength of the beer by water and salt, and then give it an intoxicating property by means of this poisonous extract.”

Similarly, rum was diluted by adding water, before sugar and molasses were added to restore the flavor and the deep brown color. Oak, sawdust and tincture of raisin stones could be added for that musky, aged flavor. Finally cayenne pepper and Cocculus indicus was mixed into the watered-down spirit to give it the necessary intoxicating kick.

In the case of gin, it wasn’t enough to merely replicate the taste. Salt, small doses of sulphuric acid, and grain of almonds were added to create “beading” — the bubbles that form on the side of the glass when the gin is poured.

Related Video: The Drinking Habits of 8 Famous Writers

https://youtu.be/-Nz0a6yFEUc

Surprisingly there was only one confirmed fatality. A group of sailors on the lash in the English port of Liverpool in 1829 were taken sick after a night drinking rum laced with serious quantities of Cocculus indicus. One died, but the rest eventually recovered.

The demand for Cocculus indicus was so great among pub landlords (and it was imported to Great Britain for no other purpose) that its market value increased in ten years from two shillings per pound to seven shillings.

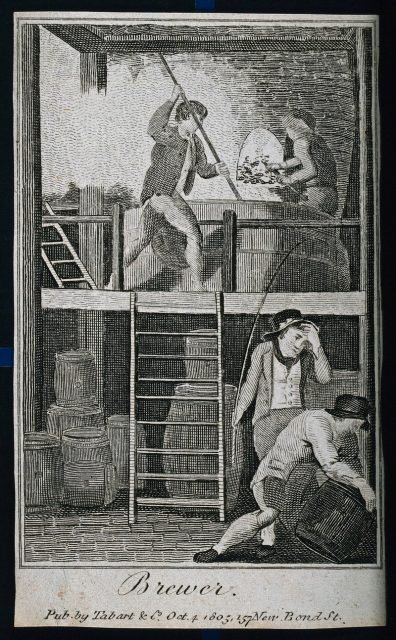

Acts of Parliament tried to cut the trade off at the source and prohibited druggists from selling these nefarious narcotics to brewers or sellers of alcohol if they suspected it was being used to spike the drinks, at pain of a £500 fine.

The brewers and publicans themselves could be fined £200. Other ingredients used in these criminal concoctions included opium (a highly narcotic depressant with a risk of long term damage to the user’s health), foxglove (which can affect the heart rate causing dizziness, blurred vision, nausea and death), tobacco, quassia (which also causes nausea), and the ominously named nux-vomica, or “poison nut.”

Another toxic treat from Southeast Asia, Strychnos nux-vomica is carefully used in various modern medicines and is the main commercial source of the strychnine used in rat poison.

Strychnine can cause muscle contractions, convulsions and death if ingested in large quantities. Even small quantities can be fatal if used continually as they build up in the body – if, for example, you were hitting up the same poisoned batch of beer over a period of many weeks.

In 1837 British medical journal The Lancet recalled a case from Germany in which “the unfortunate man […] had given to him a beer, in which nux vomica was thrown; he went home, and in 15 minutes was dead, after violent convulsions.”

Legal documents from the time describe unscrupulous brewers keeping their ingredients at home to evade raids, and smuggling them onto the premises in a specially-made coat with lots of large pockets that contained enough Cocculus indicus to taint the entire supply.

In 1864 the Inland Revenue Department reported that of 26 samples of beer taken from licensed brewers, 20 were found to contain substances designed to mask the adulterated alcohol content: 14 contained grains of paradise (a spice closely related to cardamom) with one also containing tobacco, two contained Cocculus indicus, two contained capsicum (pepper), and two contained iron sulphate (salt).

The same newspaper report explains: “There can be little doubt that the practice of adulterating beer with poisonous matters, such as tobacco and cocolum indicus is more prevalent than might be inferred from the small number of detections made as the fraud is difficult to discover unless the offender be caught in the act of committing it.”

Despite vigorous moral outrage in Parliament and the popular press, and the passage of the Food and Drugs Act of 1875, the practice of adulterating beer with poisons continued throughout the 19th century.

Rather than decline with time, the cynical practice got a new lease of life wherever brewers and bootleggers could be found operating outside the law.

This wasn’t confined to the sprawling slums of the industrial revolution’s growing cities, either. By the time of the Australian gold rush in the 1850s, there were thousands of rough and ready gold-hunters looking to unwind at the end of a hard day.

With fresh water from creeks often proven to be a breeding ground for diarrhoea, dysentery, cholera and typhoid, the miners had good reason to stick with drinking alcoholic beverages.

Concerned with drunken lawlessness from gatherings of huge numbers of young men with no fixed abode, the government banned the sale of alcohol on the Australian goldfields – it was a mistake. Instead they had handed over the market to home-brewed moonshine referred to as “sly grog.”

Read another story from us: The Greatest Beer Run in History Happened During the Vietnam War

Watering it down and making up the difference with Cocculus indicus, tobacco or opium was almost inevitable.