Black is more than a color we wear at funerals. Everywhere you look, dark colored clothing feels omnipotent. People have learned to embrace it for various occasions, from romantic dates, rock gigs, to formal business meetings. Over the centuries we have built a genuine relationship with one of the most mysterious colors on the palette.

The symbolism of black for mourning has been around since at least the times of ancient Greece. The sentiment then continued with the rise of the Roman Empire, then the Eastern Orthodox Church, and finally the Western church, after which the color settled in most of the western world.

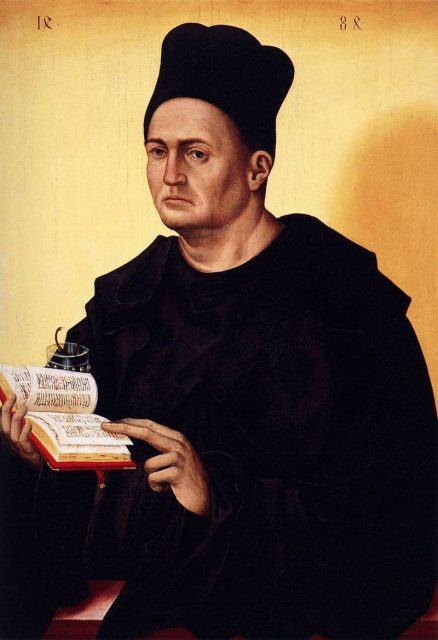

Here and there it happened that black reinvented its symbolism while retaining its old meanings. During the 14th century, dark clothes became popular within the higher classes of society. For the Middle Age royals and elite, black became a symbol of sophistication, power, and wealth.

A prominent figure to propagate wearing black in the West was Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy and ally of England who lived during the 15th century.

Philip’s Burgundy, which at the time rivaled with France, spread its influence from different cities today dotting the maps of both Belgium and France. The monarch, however, was not interested in annexing territories from his neighbors. His interests were elsewhere.

Similarly to Queen Victoria a few centuries later, Philip the Good donned black garments initially to mourn the death of someone near and dear to him — his father, who was assassinated. He never truly parted ways with the absorbing color.

Burgundy retained a prestigious status under Philip, and the monarch’s taste for dark outfits spread from within his court to other countries.

“It was under Philip that the richness and extravagance of court life in the Middle Ages reached its apogee. Philip, whose personal tastes in clothes were relatively simple, loved to surround himself with all the pomp and pageantry that the age could command,” Britannica notes.

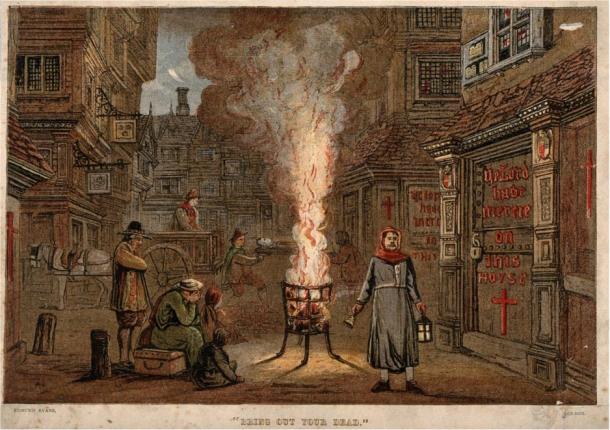

The death of Philip the Good’s father was not the sole reason why the Burgundians deemed it appropriate to veil themselves in blackness. In the times of Philip the Good, death was everywhere.

The 14th through 18th centuries saw the remorselessness of the Great Plague in Europe, popularly called the Black Death. Great famines and lengthy wars also mercilessly tarnished the continent. Black seemed an appropriate color to adopt in a number of ways.

In the Spanish courts, the color carried even greater significance. At their greatest, different European powers sought to embrace black, but the Spanish nabbed an inviolable association with it. It came with a distinct designation: Spanish black.

A renowned oil on canvas portrait by Italian painter Titian, depicting the Spanish king Charles V, descendant from three superior dynasties in Europe, shows the king in ultimate black. In striking contrast with his garments, the monarch’s complexion and hands look rather pale. In fact, the portraiture of European monarchs is abundant with the color of death. Charles V himself has several more portraits presenting him in black.

In England, Queen Elizabeth I, praised by her people for successfully confronting the Spanish Armada that attempted to invade her island, wore black on many occasions. Her Sieve Portrait from 1583 is a splendid example.

Between the Middle Ages and modernity, dark fashion somewhat evolved, particularly in the way it has been worn by the different genders.

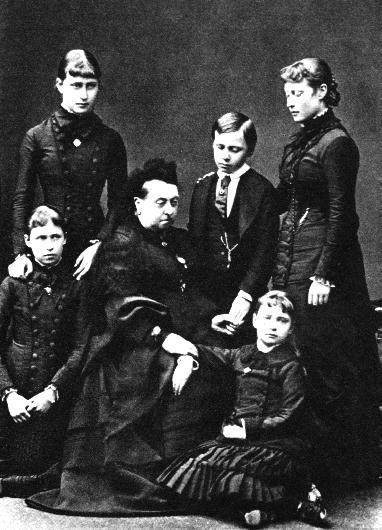

For a while, black dresses would denote the mourning cycles of widowed women, par excellence Queen Victoria during the 19th century. If there is a legacy left from that era it survives in Gothic subculture and fashion, where the expected dress code involves long, dark gowns, and heavy application of makeup.

On other occasions, women were free to stay more jubilant in their clothing choices. But not men.

Men gradually distanced themselves from various fashion trends that hinted at beauty, joy or even triviality. This phenomenon which commenced at the closure of the 18th century has been described as the Great Male Renunciation by the 20th century psychoanalyst John Flügel.

The Great Renunciation dictated a very uniform approach to how men dressed. Suits. As you might imagine most suits clung to the usage of darker colors. Several world events propelled this significant fashion transformation, including the wake of Republicanism in the United States.

“The black, dark gray, or navy pinstripe three-piece and later two-piece suit in flannel or worsted, with black shoes and sober tie, has become the staple getup for men in official positions high and low, for lawyers, doctors, businessmen, clerics, estate agents, undertakers, and even junior clerks and shop assistants. In the nineteenth century, it was adopted by those in service, by ‘the gentleman’s gentleman’ as well as the gentleman,” writes Nina Edwards for the Paris Review.

“In the 1980s, those who wanted to seem mature and able in the business world wore ‘designer’ dark business suits, sleeker and more figure hugging than those of the 1970s, and more recently there has been a resurgence in male high fashion for discreetly expensive dark suiting, perhaps as a defense in a time of uncertain financial stability.”

For much of history, attempts by men to shatter uniformity has come at their own risk of being laughed at. Adding a pair of red socks for example. In this context, most colorful and playful fashion details have been put aside for women’s apparel.

Women have seen other breakthrough moments with black attire, however. One of them was the appearance of the Chanel black dress. Its original presentation on the cover of Vogue magazine in 1926 billed the dress as “The Ford” of a woman’s wardrobe. “It also promoted black as smart, elegant, attractive,” according to Quartz.

Fashion designers would rely on those attributes heavily in the decades to come, reviving black on the runways again and again.

While we opt for black for the most mundane of everyday wear, black and dark colors have been continually exploited by the unyielding machinery of the business world, religion, church, or as of more recently even the sex industry.