Located slap bang in the middle of Europe, Poland often found itself trapped between voraciously expanding empires. This meant that throughout its history, the Polish nation, often seen as an obstacle in the eyes of its more ambitious, aggressive, and frequently more powerful neighbors, had to resort to desperate and often farcical measures to survive and maintain its unique cultural character.

Whether living under Catherine the Great, Otto von Bismarck, or Adolf Hitler, those who fought to preserve their national identity faced varying degrees of animosity from the occupying forces, keen to weed out the inconveniently defiant Poles.

One man whose name came to symbolize that spirit of resistance and resourcefulness was Michał Drzymała — a Polish peasant, born in the Kingdom of Prussia on September 13, 1857.

He gained worldwide notability at the beginning of the 20th century, when the story of his bizarre dispute with the Prussian administration, regarding permission to build a house on a plot of land he had purchased in the village of Kaisertreu, was picked up by journalists around the globe.

Like many of those belonging to his social class, Michał Drzymała toiled his entire life in a bid to escape the poverty cycle by purchasing land, where he could build a family home for himself and the generations to come.

According to Prussian law, prospective home-owners had to seek consent — much like today’s planning permission — from the local administration, before commencing any construction work.

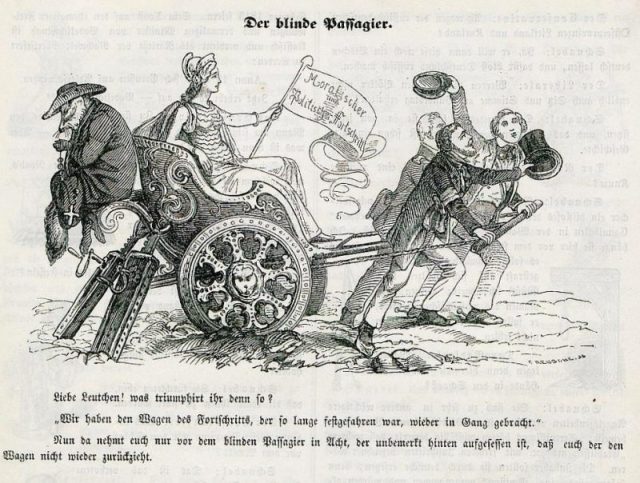

Fulfilling the Kulturkampf (culture fight) politics of Germanization, common on territories laid claim to by both Prussians and Germans throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, which favored the German-speaking population, local authorities used the aforementioned planning permission requirement to discourage ethnic Poles from settling on the more sought-after land.

Under the 1904 Law Regarding Limitation of Polish Parcellation Activity, the legislation also prohibited Polish people from establishing farms and building new households.

Drzymała fell victim to this glaring discrimination, and with no roof over his head was forced to improvise — he purchased a circus wagon, which would become his family home for the years to come.

Adamant that any dwelling stationary for a period of more than 24 hours is a house, the Prussian authorities attempted to remove Drzymała’s wagon, however, the canny peasant would not give up his fight easily.

Playing the infamous Prussian bureaucracy machine at its own game, the folk hero took advantage of the legislation used against him, and in an absurd turn of events resorted to moving his trailer by a few inches every night.

Astonishingly, he was able to circumvent the discriminatory building regulations and the Kafkaesque dispute continued for four years, making a mockery of the government’s oppressive directive and, ironically, attesting to the strength of the rule of law in Prussia.

Eventually, hounded by officials who used every law in the book to make his life a misery, Michał Drzymała abandoned the plot of land in question, and instead purchased a nearby property with a house already built on it.

A farm house in the Drzymały estate in Rakowienice (1907)

Drzymała’s stubbornness became the symbol of grass-roots defiance to Prussian (and later German) oppression against its Polish citizens. The power of his rebellion was not lost on the German-speakers either – following his death in 1937, not one of the local carpenters was willing to build a coffin for Drzymała, and instead, he was buried in a casket crafted by a Polish furniture-maker.

Two years later, his tomb was deliberately destroyed by German soldiers advancing into Poland during the initial stages of the war. The Nazis knew Drzymala’s legacy had no place in the Europe they envisaged.

In 1918 the land returned to Polish hands, and in 1939 the then village of Podgradowice, formerly known as Kaisertreu, was renamed Drzymałowo in honour of Poland’s tenacious folk hero and his unwillingness to succumb to Prussian subjugation.

Since his death, the story of the iron-willed smallholder has been immortalized by poets and authors, and streets named after Michał Drzymała can be found in most Polish cities.

Read another story from us: The Deadliest Female Sniper in History

The national champion was also posthumously awarded the Polish Cross of Merit. Over 100 years on, the euphemistic “circus on wheels,” inspired by the events described above, remains an element of the Polish vernacular, synonymous with tragicomedy and situations convoluted to the point of farcicality.