The scientific analysis of skeletons found in the wreck of the sunken Tudor warship Mary Rose is offering up surprising proof about the makeup of English ships 500 years ago.

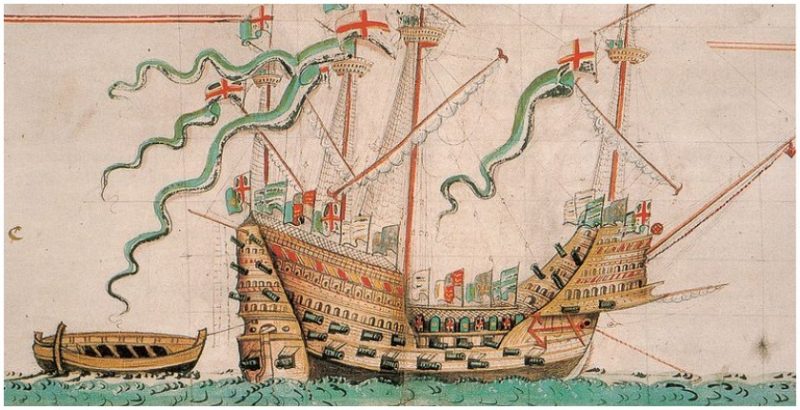

A carrack-style ocean-going warship, Mary Rose was launched in July 1511 as one of the earliest purpose-built warships in the world and one of the largest in the English navy. Serving in battles with France, Scotland, and Brittany, it sunk in the Battle of the Solent on July 19, 1545.

During the battle, an eyewitness reported Mary Rose fired all of its cannon on one side and as it was turning to bring the rest of its guns to bear, a sudden gust of wind tipped the warship to one side and water flooded in through the open gun ports.

Overloading the aging ship with heavier and heavier guns was also thought to have played a part in the disaster which tragically took over 500 lives to the bottom of the Solent, the strait separating England from the Isle of Wight and home to the vital ports of Southampton and Portsmouth.

Mary Rose was raised from the seabed in 1988 and taken to the museum Portsmouth Historic Dockyard where it could be studied and preserved.

The Many Faces of Tudor England, an ongoing project run by the Mary Rose Trust, used isotype analysis and DNA testing of teeth and bones to unravel the life stories and ancestries of the long-dead crew who perished in service of King Henry VIII. Until recently science simply wasn’t up to the task as the DNA had degraded over the 500 years in Davey Jones’ Locker and had been contaminated by algae, mollusks, and cockles.

Of the eight remains that have been recently analysed, two of them are believed to be of African heritage. One crewman, who the investigators called “Henry”, was a muscular teenager aged between 14 and 16. A tooth was extracted and the data it unlocked suggests that Henry’s father was of North African origin, possible Moroccan or Mozabite Berber, and his mother may have been North African or Southern European.

Henry, however, might have been a second generation immigrant as isotype analysis confirmed that he grew up in England — in an area of high rainfall and likely within 30 miles of the coast.

Related Video: Diving down to the eerie wreck of the USS Arizona

https://youtu.be/VQLhoMSGvO0

The other African in the ship’s company was one of Henry VIII’s elite archers, whose skeleton was found trapped under the axel of a bronze cannon. The “Archer Royal”, as the team call him, was tall at 5 feet 11 inches and had a spinal disfigurement and strain to the shoulder consistent with a lifetime spent practicing with the infamous English longbow — pulling back the bow was akin to lifting a 200-pound weight.

The testament to his status as a royal archer was a leather wristguard decorated with the Royal Arms of England and the badges of Henry VIII’s first wife, the Spanish-born Catherine of Aragon – the triple turret of Castile and the pomegranate symbol of Granada.

At a time when most elite longbowmen were recruited from Wales or Southern England, oxygen isotope analysis on the teeth of the Archer Royal reveal that he grew up in a hotter climate, while the lack of sulfur and evidence of seafood in his diet led researchers to conclude that he likely came from the interior of North Africa, over 30 miles from the coast.

That the Archer Royal died wearing Catherine of Aragon’s badges is notable. It was only 50 years earlier that her parents, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, had driven the last of the Muslim conquerors from Spain in the Reconquista.

Although a “Moorish” population of around 300,000 remained in Iberia, most were converted to Christianity through coercion and called Moriscos (“little Moors”). Moor was a catch-all term for North African Arabs and Berbers, as well as European Muslims, and many Moorish servants and slaves were brought into the Spanish royal household as a symbol of their supremacy over the Moors.

One Moorish chambermaid, Catalina of Motril, followed her mistress, Catherine of Aragon, to England. There were others in her retinue, as the Tudor statesman Thomas More described her servants offensively (and inaccurately) as “undersized, barefoot, pygmy Ethiopians.”

Read another story from us: Research Team Close to Finding Antarctica’s Most Famous Shipwreck

Another member of the Spanish delegation to leave his presence in the records is the musician John Blanke (from “blanc”, Spanish for white) who became a well-paid fixture in the English court.