Archaeologists digging in Jordan’s Black Desert have discovered a piece of charred bread that is thought to have been baked 14,400 years ago. According to Haaretz, this exciting find suggests that humans were making bread from wild grains thousands of years before the so-called “agricultural revolution” in which grains were cultivated systematically.

The find was discovered at a site named Shubayqa, once occupied by a group of hunter-gatherers known as the Natufians, 130 miles northeast of the Jordanian capital Amman.

An international team published the findings of the dig in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in July last year, explaining that they had discovered a charred cracker that was found to have “bread like” properties.

According to Amaia Arranz Otaegui, part of the team that made the discovery, advanced analysis techniques revealed that it was consistent with other ancient flatbreads discovered in the Levant in the Roman period.

Over 20 fragments of this ancient bread were found in a fire pit in Shubayqa, along with the remains of other foodstuffs. It is believed that the bread was made using a technique that has essentially remained unchanged for millennia, combining flour and water to make a dough, which was then kneaded and baked over an open fire.

The fire pit and the collective remains were all dated to 14,400 years ago, when the semi-sedentary Natufians dominated the Eastern Mediterranean.

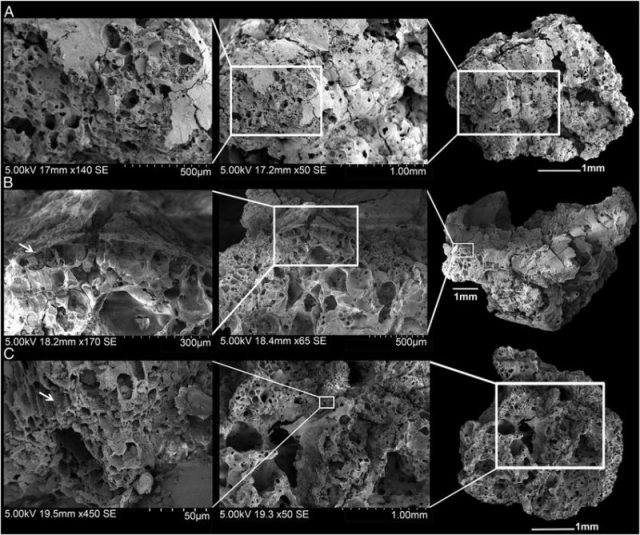

The bread found at Shubayqa is preserved as tiny, charred fragments, and so the team had to use state-of-the-art techniques in order to accurately identify it.

According to Haaretz, they used advanced imaging techniques using scanning electron microscopy, which provided an extremely accurate reading of the composition of the sample. After close analysis, they were able to confirm that the sample was indeed analogous to our modern bread.

According to Haaretz, the team also found samples of barley, oats and wheat at the site. This is highly unusual, as these crops did not become domesticated until around 4,000 years later. It appears, therefore, that the Natufians made bread from wild grains that they foraged themselves.

Although there is some evidence for plant cultivation in human societies going back 23,000 years, this should not be interpreted as proof of widespread agricultural practices.

The cultivation of crops as a food supply occurred sporadically in Neolithic societies in the Levant, and it was not until 9500-8600 BC that agriculture became widespread.

Even in this period, according to Professor Tobias Richter who led the team at Shubayqa, crop cultivation did not provide the basis for the human diet, which would have been heavily supplemented with plants foraged from the wild. Wheat and barley were not systematically cultivated until much later.

According to Haaretz, the archaeologists were able to determine whether the grains had been cultivated deliberately or foraged from the wild by close analysis of their composition. Grains that occur naturally rely on the elements to ensure distribution of their “spikelets” in order to reproduce. However, grains cultivated by humans develop differently, as humans manually shake the sheaves in order to ensure effective distribution.

Over time, these strains of wheat become dependent on human cultivation, in a process known as domestication syndrome. Richter argues that the evidence found in the Levant suggests that the development of true agriculture, defined as systematic, settled development of the land for the production of food, took many thousands of years to develop, and involved considerable trial and error.

There is no evidence of settled agriculture at Shubayqa, and the grains discovered in the food fragments were wild. This means that the find contains some of the earliest hard evidence for bread production using wild, foraged grains. A large stone mortar also found at the site is assumed to have been used for grinding the grains into flour.

According to Richter, it is thought that the bread would have been very similar to the unleavened flatbreads identified at other Neolithic and later Roman sites in the region.

Read another story from us: 2000-year-old preserved loaf of bread found in the ruins of Pompeii

He suggests that these early practices of cooking with wild grains may have inspired the Neolithic communities of the Levant to experiment with cultivating their own varieties, leading to some of the earliest farms in the region. This important find is, therefore, part of the wider story of the very earliest development of agricultural practices in ancient human society.