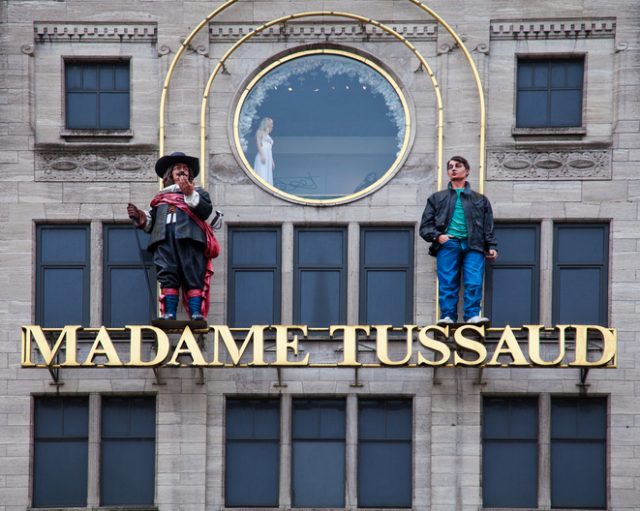

Every year hundreds of thousands of people visit one of Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museums. There are 21 of these unique venues throughout the world, including six in the United States.

The first wax museum was opened in London in 1835, and today attracts around 2.5 million visitors every year. Of course, the museum is famous for one reason: the many incredibly life-like wax figures of famous (and infamous) people it holds.

Though many of the people who go to Madame Tussaud’s do so out of curiosity, most visitors are interested in celebrities, history or both, and Tussaud’s offers them the best and only opportunity to “meet” their favorite celebrities or heroes.

Many people know of her museums, but who was Madame Tussaud herself? For starters, Tussaud was not her real name. She was born Marie Grosholtz in the French border city of Strasbourg in 1761, but as a young child, her mother relocated with to her to Bern, Switzerland.

In Bern, her mother was the maid for a doctor named Curtius — who made wax models. Curtius’ creations were most likely a way to help anatomy students, at a time when working on cadavers was still frowned upon and they were difficult to come by.

Eventually Curtius, who was quite skilled at wax modeling, was convinced to move to Paris and began to create not only anatomical wax models, but also likenesses of famous people of the day.

By 1765, Curtius had given up medicine and was making a very good living creating portraits of the aristocrats and celebrities of Paris. He began to teach Marie how to create sculptures when she was in her early teens. In 1770, Curtius’ works were put on exhibition and were eventually displayed at the Palais Royale, the Paris residence of the king.

In this way, Marie began to make the acquaintance of some of the movers and shakers of Parisian high society. In 1777, she completed her first wax figure in the image of the philosopher and writer Voltaire, possibly the most famous man in France.

In 1782, Curtius opened a permanent exhibition hall, and Marie saw first hand how much money could be made creating wax figures. Unfortunately for her, the French Revolution was just seven years away.

The “official” beginning of the Revolution was July 14, 1789, with the Storming of the Bastille, but that act was precipitated by an event that Marie Grosholtz was indirectly involved in. On July 12, a mob rushed into Curtius’ exhibition hall and removed the busts of two hated figures of the time: The king’s brother, the Duke of Orleans, and Jacques Neckar, the finance minister.

The crowd then paraded about the neighborhood with the figures and held a mock funeral for them. The mob was then fired on by the national guard and this helped to fan the flames which resulted in the Storming of the Bastille.

One of the first “celebrity” figures that Marie created was that of Jean-Paul Marat, an incendiary revolutionary journalist who had been assassinated in his bath by Charlotte Corday, who supported a rival political party.

“The Death of Marat” is a famous painting by Revolutionary artist Jacques-Louis David, but Marie was summoned there by Marat’s allies and created a very life-like sculpture of the firebrand. Unlike David’s painting, Marie’s sculpture showed Marat as he was: a sickly and scrofulous man rotting away in his tub.

As things became more and more violent in Paris, Marie was often summoned to create wax figures of decapitated heads so the revolutionaries could send them to the provinces as propaganda.

As the French Revolution became more and more radical, Curtius and Marie found themselves in the cross-hairs. Curtius had moved in aristocratic circles before the revolution, and naturally, Marie had as well.

During the Reign of Terror in 1793-4, they were both arrested as possible counter-revolutionaries. It was also illegal for people to own busts and portraits of people who were deemed “Enemies of the People”, and of course, Marie and Curtius owned plenty of them.

Fortunately, Marie was released through the influence of a powerful friend as the Terror eased, but she had one more decapitated head to cast: that of the chief organizer of the Terror, Maximilien Robespierre.

In 1794, the year the Terror ended, Curtius died, leaving everything to Marie. She was now very well-off but unprotected in an uncertain time, so she married an engineer named François Tussaud. As it turned out, her husband was about as bright as one of her wax figures, and almost destroyed her financially with bad investments.

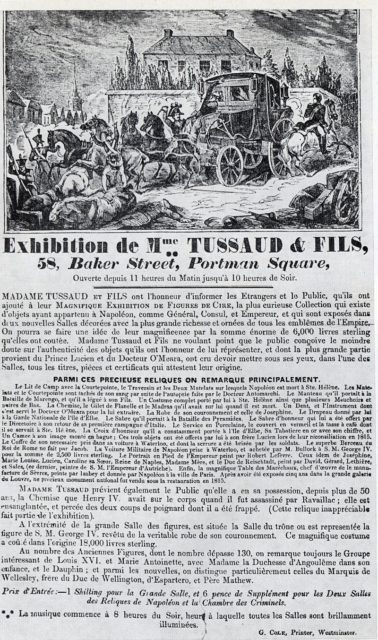

In 1802, Marie (now Madame Tussaud) was invited to London to exhibit her figures – people there were fascinated by the events in France. Though the promoter got away with half her profits, the show taught Marie that there was a demand for her figures internationally.

Not able to return to France because of the Napoleonic Wars, she began to create figures of famous people from the British Isles — both living and historical — and toured England, Ireland and Scotland. By 1831, she was a rich woman and opened a permanent exhibition hall in Baker Street.

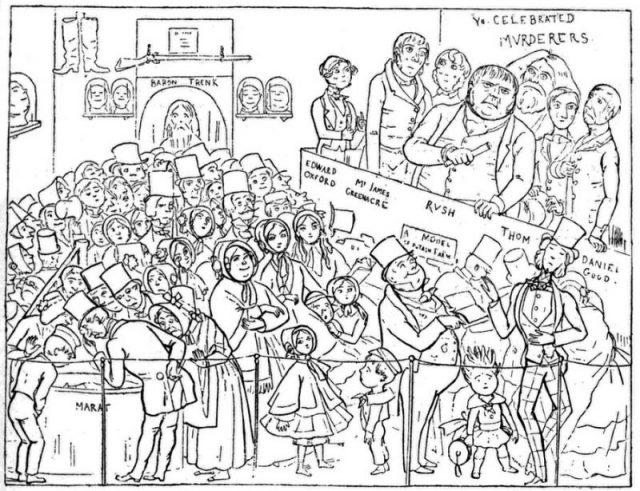

Though people did come to see likenesses of the royal family and other notables of the time, Tussaud’s notoriety in England came from her exhibit called “The Chamber of Horrors”.

There, in the age before photography, people could indulge their dark sides and see the guillotined heads of the French Revolution, and figures of infamous criminals – including the hated Napoleon.

Read another story from us: Cache of Rare Papers Found in Vincent van Gogh’s Former London Home

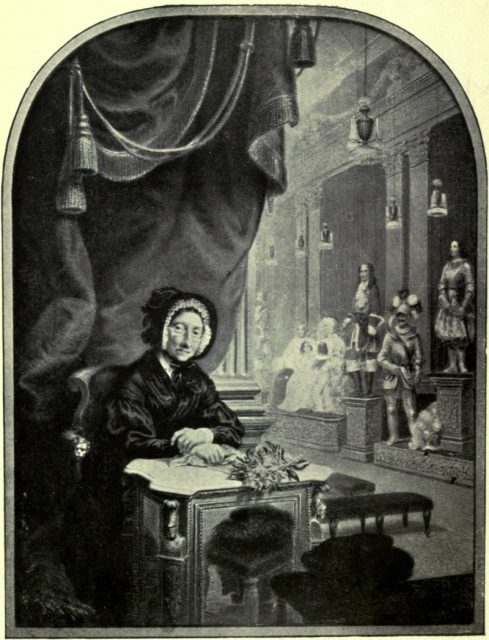

One of the main attractions was Madame Tussaud herself, who told tales of her time in France and the people she met. As a young woman, Marie was an art tutor to the King’s sister and had made a wax figure of the king in both life and death (well, just his head). She had been witness to some of the most earth-shaking events that Europe had ever seen, and came out alive.

Madame Tussaud died in 1850 at age 89. Just before she passed, a wax figure of her was created. It is still on display at the London museum.