A pioneering genetic study is shedding new light on the way in which migration from Central Europe transformed the society and peoples of the Iberian Peninsula during the Bronze Age, according to the BBC.

The study, conducted by a large interdisciplinary team of researchers from across Europe and the United States, sampled DNA from the remains of 403 inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula who lived between 6000 BC and 1600 AD. This ambitious genetic survey covers almost 8,000 years of human development and is the largest study ever to be conducted of this kind.

According to the BBC, the aim of the project was to understand change and development in the population of the Iberian Peninsula from the Neolithic period to the modern era.

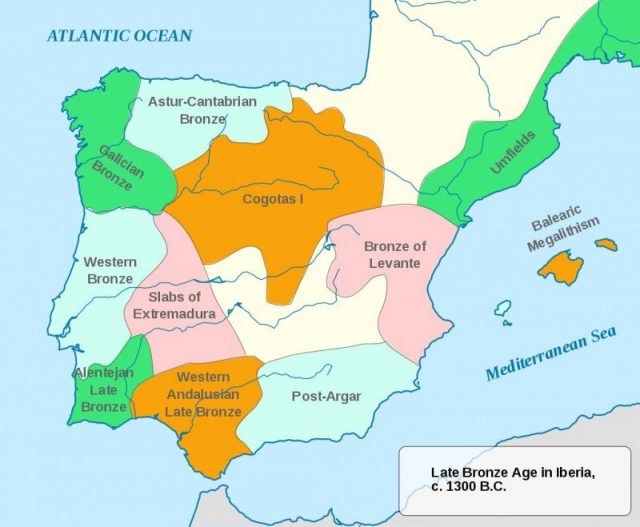

It covered the populations of the area that now includes Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar and Andorra across 8,000 years of history, building a rich picture of the types of people and societies that moved into the region at different points in time.

Historically, and partly due to its strategic position at the Western end of the Mediterranean, Iberia has long been a cultural crossroads, the meeting place of many different types of cultures and peoples.

However, this study shed considerable light on a seismic event in Iberian population history: the replacement of large numbers of its Neolithic inhabitants by migrants from the Central Asian steppe.

The movement of peoples across Europe from Central Asia during the 3rd millennium BC is a well-known phenomenon. As groups moved into Europe from what is now Russia, they developed sophisticated techniques in bronze working and distinctive styles of production of beaker-shaped drinking vessels that meant they were dubbed the ‘Bell Beaker’ society by modern archaeologists.

According to the BBC, they swept through Eastern Europe, even coming as far west as Britain and Ireland, where it is thought that they replaced up to 90 percent of the Neolithic inhabitants of the region.

Although significant work has been done on Bell Beaker material culture, archaeologists have not been able to construct a clear picture of the impact of Beaker migration on Iberian populations.

This pioneering genetic study helps us to understand the ways in which the wave of migrants from Central Asia crossed the Pyrenees and transformed Iberian society.

The study indicated that between 2500 and 2000 BC, 40 percent of Iberia’s ancestry and nearly 100 percent of its Y-chromosomes were replaced by peoples with Central Asian steppe ancestry.

The study determined this population change by specifically analyzing Y-chromosomes in the genetic samples, which are used to trace male lineage.

Using this data, the team was able to assert that local male lineages had been largely eliminated by the newcomers by about 2000 BC, constituting a radical change in overall patterns of ancestry.

According to the BBC, the team took pains to assert that this population “replacement” did not necessarily occur through invasion, domination or forced displacement of local populations.

Rather, it is likely that the newcomers represented a more sophisticated society, and their high social status may have given them a considerable advantage when it came to reproductive success. There is no evidence of large-scale violence in this period, but historians do believe that social change may have contributed to the population shift.

According to the BBC, the introduction of strictly patrilineal models of succession and inheritance may have amplified the tendency for the newcomers to be more successful than their local male counterparts.

Patriarchal societies with primogeniture as the dominant mode of inheritance would have resulted in a proliferation of sub-clans and tribes, as younger sons established their own clans outside the social boundaries of that of their parents. According to the study, this may account for the rapid population change observed in the genetic data.

This study is a landmark case demonstrating the way in which interdisciplinary research is transforming our understanding of ancient societies in Europe.

Read another story from us: Anglo-Saxon Pendant Found in England Declared To Be Treasure

It is hoped that further studies of this kind, combining genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence, will allow us to better understand the important impact that migratory patterns had on Bronze Age European societies.