Wars are fought for all sorts of reasons: economic security, power, revenge, politics, international alliances. The list is almost endless and still sometimes includes conflict between personalities that simply do not like each other, though this was much more common in the days of absolute monarchy.

Though it was fought in the wider context of a really important war, one conflict stands out for its stupidity – the so-called “War of the Bucket” between the Italian city-states of Modena and Bologna. The name of the war is not a code for some political movement or the nickname of some prince. They really fought over a bucket. During the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries, the powers of Europe fought an on and off series of wars known as the Guelph and Ghibelline Wars.

These wars were part of the struggle between the Catholic Church and a number of secular royalty known as the Investiture Controversy. At stake was the power of kings or local rulers to appoint or “invest” local church leaders, such as bishops and abbots.

The hope of some rulers was that by appointing men friendly to them, aristocrats would have fewer difficulties from the local Church over matters in their realms. Of course, the Pope, the Catholic Church and its allies opposed this, seeing their appointment of church officials as a way of keeping a balance of power.

This conflict involved kings and rulers from much of the Holy Roman Empire, including the city-states of northern and central Italy. The Guelphs supported the Papacy and the Ghibellines the secular rulers seeking more power over the Church in their domains.

The name Guelphs is a bastardization of the name of a royal Bavarian family, the House of Welf. The Ghibellines took their name from the name of the castle of a Swabian (Germany) foe of the House of Welf. This was the castle of Waiblingen, turned into “Ghibellino” by the Italians. Obviously, their respective rulers had supported one side of the argument or the other.

Now, within this important and costly series of wars that lasted centuries, the neighboring city-states of Modena and Bologna in central northern Italy took opposing sides.

The Modenese were Ghibellines and the Bolognese, Guelphs. Italy did not become a nation until the 19th century and for much of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, was split into dozens of powerful city-states, each of which fought each other for political, military and economic control. Modena and Bologna, just over 27 miles apart, were frequent rivals.

Related Video: Rare Footage Of Civil War Veterans Doing The Rebel Yell

https://youtu.be/mYpNz7bvB1g

In 1325, a group of Modenese soldiers (probably drunk, bored out of their skulls, or both) snuck into Bologna itself and stole a bucket from the city’s central well. That their enemy could sneak into their city with impunity and steal something from them was an affront to the honor of the Bolognese, who demanded that the Modenese return the stolen bucket, which they refused to do.

An oak bucket caused the Bolognese to mobilize their powerful army: 30,000 infantry and 2,000 horsemen. For their part, the Modenese, who should really have had second thoughts by this time, mobilized their 5,000 infantry and 2,000 horsemen.

They met near the modern village of Zappolino, about halfway between the two cities to the south. There, the Modenese found themselves drastically outnumbered and out of position. The Bolognese had the high ground and the men from Modena were scattered about the valley below.

What the Bolognese had in numbers they must have given up in leadership, for within a matter of just a few hours, the Modenese had not only driven them off the battlefield but were chasing them back to Bologna with their tails between their legs.

The Modenese soldiers broke into Bologna, destroyed several small castles and to top it all off, destroyed a sluice on the local river which supplied Bologna with water. It’s almost as if the Modenese were saying “You wanted your bucket? Well, you don’t need it anymore. You don’t have any water!”

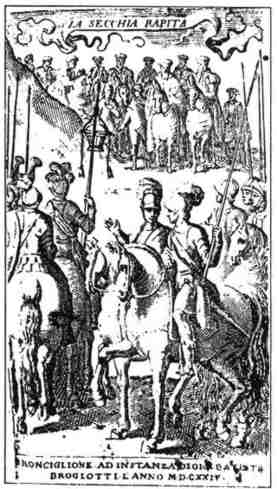

Making sure the people of Bologna were truly humiliated, the Modenese then staged a parade around the city, re-enacting both the raid that took the bucket and the battle that followed. And of course, just before they left the area, the Modenese took a bucket from a well outside the city so those locals couldn’t have water either. Before you laugh too hard: two thousand men were butchered in the brief “War of the Bucket”.

Read another story from us: Henry VIII’s Famous Sunken Warship the ‘Mary Rose’ had African Crew

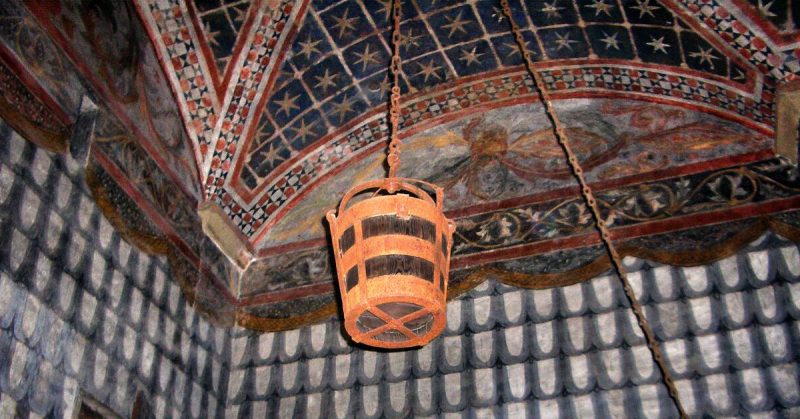

When the Guelph and Ghibelline Wars finally ended, the Modenese returned some acreage they had seized in the war. They kept the bucket though – it resides in the basement of a medieval tower. A replica of the bucket hangs from the ceiling in the Modenese town hall. 694 years later.