History’s first version of the “vagina monologues” has been found and dated back to Medieval times. One of the world’s oldest erotic poems is now older than first thought. A discovery at Melk Abbey in Austria has shifted the infamous Der Rosendor, or The Rose Thorn, back 200 years, throwing open the question of sexuality in medieval times.

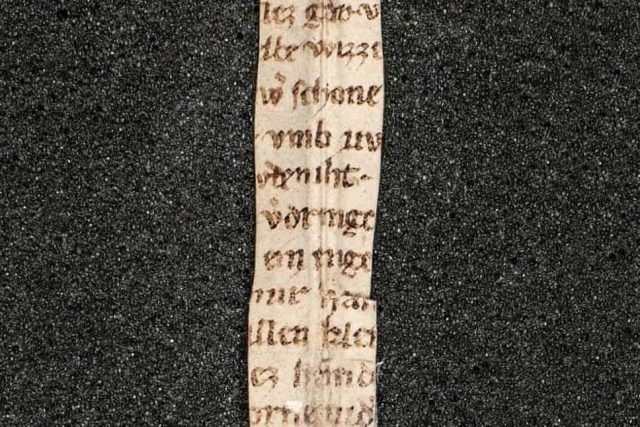

Christine Glaßner from ÖAW (Austrian Academy of Sciences) was researching ancient manuscripts in the Abbey’s archive when she found the poem, or rather some of it. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she identified “a long thin strip of parchment on which a few letters per line are visible”, meaning that “The parchment on which the poem was written was cut up and reused as binding in a Latin theological text.”

Such recycling was standard practice – though it’s unclear whether religious thrift or censorship is the reason for it winding up in a bind. The poem may have been innocently cut up or its controversial content hidden from view. Either way parchment was too valuable to waste, with even controversial subject matter subject to economic forces.

Two copies of Der Rosendor from around 1500, the Dresden and Karlsruhe Codexes, have been found and pored over to date. The Guardian reports they “are a constant fascination for medievalists who consider it one of the first ever erotic poems.” The newly-uncovered fragment measures 22 cm by 1.5.cm. Despite its limited size, it has caused a stir in medievalist circles.

Experts from both Austria and Germany are examining the erotic snippet, which has game-changing implications. A press release from the Academy describes how previously “it had been assumed that such openness regarding sexuality in the German-speaking world did not appear until the end of the Middle Ages, for example in the urban culture of the 15th century.”

Furthermore, things may have gone beyond committing scandalous content to parchment. It’s speculated that “erotic poetry was written, recited and perhaps even staged” a couple of centuries earlier. A definite contrast to the common perception of medieval times as a no go area for sauciness.

The question on everyone’s lips concerns the subject of Der Rosendor. Put simply, it has been compared to today’s Vagina Monologues. Presenting readers with the tale of a woman arguing with her private parts, it is viewed as surprisingly sophisticated. What are the two parties in dispute about? The woman, a virgin, believes men are drawn to her attractive appearance. Whereas the expressive vulva puts male interest solely down to itself.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/utw0IVJcGK0

Smithsonian quotes Glaßner, who says “At its core is an incredibly clever story, because of the very fact that it demonstrates that you cannot separate a person from their sex”.

A resolution is reached, though it isn’t as progressive as it seems. The narrator of the tale is a man and it is he who brings the two sides of the argument together… quite literally. The article comments, “The narrator then steps in to offer his aid, and —in a moment that in 2019 that reads, decidedly, creepy—pushes the two back together in a less-than-chivalrous manner.”

Der Rosendor is a far cry from what the Academy’s release calls the “love poetry of minstrelsy”. And long before the Vagina Monologues appeared talking genitalia were popping up through history, though this Medieval find makes it the earliest. Most notably the 1748 novel Les bijoux indiscrets goes as far as depicting a magical ring that gives said organs the power of speech. The Rose Thorn has the dubious distinction of being German literature’s first known case of a verbose anatomy.

Related Article: The Chastity Belt – Medieval Myth or Reality?

The find certainly puts today’s racy climate in context, though it should be pointed out that historians have been lifting the lid on medieval society for a long time. However, further hard evidence of this convention-defying poem underlines historical reality in a way no amount of dry explanation ever could.