The magic of DNA revealing an ancient culture is at it again. It’s well known that North Africa and Eurasia have been home to many of our earliest civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt’s Old, Middle, and New kingdoms, Sumer, Babylon, and several notable Chinese dynasties. There have also been smaller, less well-known civilizations that have risen and fallen over the millennia. One of them is the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC).

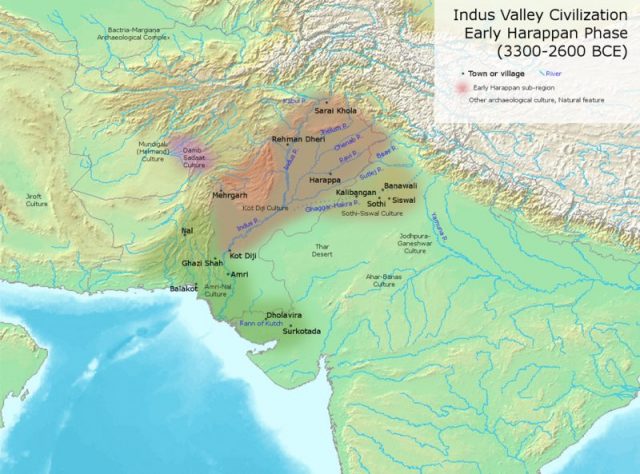

This civilization, which is also known as the Harappan civilization, was strung out along the basin of the Indus River, covering the area that is now Pakistan, Afghanistan, and part of India. Archaeological expeditions in that area have found evidence of religious practices that date back to 5500 BCE, of farming villages from 4000 BCE, and of complete civilization from 3000 BCE.

Most of the excavations have happened in two places: the old city of Mohenjo-Daro and the city of Harappa. The evidence suggests that the cities were comparable, or even superior, to those in the areas mentioned above, with wells, bathrooms, and underground drainage. Even so, relatively little has been known about the people who lived there until recently, at least in part because historians hadn’t worked out much of the Harappan language.

Now, however, scientists have sequenced the genome of someone from the IVC for the first time, according to Smithsonian. They found a small amount of DNA from the remains of a woman in a 4,500 year old burial site, allowing them to accomplish the sequencing. That work, in combination with DNA analysis done from a wider swathe of the area, has also given researchers some new questions about the beginnings of agriculture in the region in the ancient past.

The sequenced genome was compared with others from South Asia, and suggests that the IVC is the genetic root of most modern Indians. DNA from both groups shows the same mix of Iranian DNA and that of certain Southeast Asian hunter-gatherer societies, according to Harvard Medical School geneticist David Reich.

The woman’s DNA also had evidence of some things that surprised researchers, such as a lack of genetic relationship with the Steppe pastoralists whose genes are frequently present in modern South Asians, as well as among Europeans and other groups. This suggests that the entry of the Steppe genes into the South Asian gene pool occurred after the fall of the IVC.

The DNA findings also suggest things about how the ancient culture of the Indo-European languages spread across the world. Because there are genes from Iranian farmers in many modern South Asians, some historians have come to believe that agriculture came to that region courtesy of the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East. The genes from the Harappan remains don’t make much of a contribution to the lineage logical for that theory, which means that farming in that region may have begun from exchange of ideas or even arose spontaneously, as opposed to being the result of a mass migration from Iran.

In other words, the Harappan woman’s DNA has given researchers a way to test the validity of some of what they think they’ve figured out about ancient life in South Asia.

Despite the fact that the IVC covered a large area of land and the fact that their cities were large, well planned, and had good public infrastructure, the civilization remained unknown to historians until 1921 when archaeological digs at Harappa started to uncover the city. They have uncovered considerable urban ruins; however the language of the people was largely made up of pictures and symbols, making it difficult to work out and gain a deeper understanding of the culture. For example, historians still haven’t been able to determine whether the cities in the area were independent, or part of a cohesive kingdom.

The Encyclopedia of Ancient History tells us that the IVC began its slow decline around 1800 BCE. Symptoms include writing beginning to fall out of use along with a standardized system of weights and measures that would be used for trade; without trade, its connection to the Near East would be lost. Over time, the cities began to be abandoned for reasons that aren’t completely clear.

Related Article: The ‘Skeleton Lake’ Mystery Deepens after Surprising Results of DNA Tests

The most popular theory is that it was due to changes in the climate. The Saraswati River began to dry up around 1900 BCE. Some experts say there was a massive flood in the area. Either option would have taken a terrible toll on the agriculture of the region and could have been behind people drifting away.

Perhaps further analysis of the DNA of the ancient culture of the Harappan woman may help provide more clues about what actually happened to her people and her civilization as well as a better understanding of the ancient origins and development of South Asian populations.