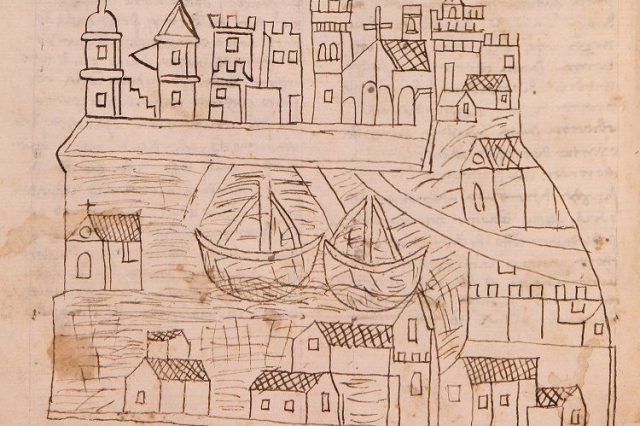

The oldest ever illustration of Venice has been discovered. Made by a traveling friar in the 14th century, it’s finally been brought to light in the 21st century. Dr Sandra Toffolo noticed the Renaissance era depiction whilst examining an original manuscript by Niccolò da Poggibonsi titled Libro d’Oltramare (translation: Book of Outremer/Overseas).

The holy man and pilgrim wrote this historic guidebook in pen after he’d completed an epic 4 year journey round Jerusalem, Damascus, Cairo and Alexandria. Though crude by today’s standards, the image of Venice with its structures, waterways and gondolas is unmistakable.

In its own unique way it brings this much-loved location to life. The friar who followed his artistic urge was no slouch. He also produced drawings of Cairo’s buildings and even elephants. As befitting a man in his position, he also drew sacred sites such as Solomon’s Temple and the Dome of the Rock.

According to Smithsonian.com he “took great care with his travelogue, taking measurements of landmarks in the Holy Land by counting paces or comparing them to the length of his arm. Every day, he recorded these observations in his tablets.”

His aim was to capture the sights as accurately as possible, and he asked God and the Saints for help in doing so. By the sounds of things, he did just fine. Committing what he saw to tablets made of gesso, or white chalky mixture, he then produced the manuscript. This has been sitting in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence, where Dr Toffolo observed the illustration last May.

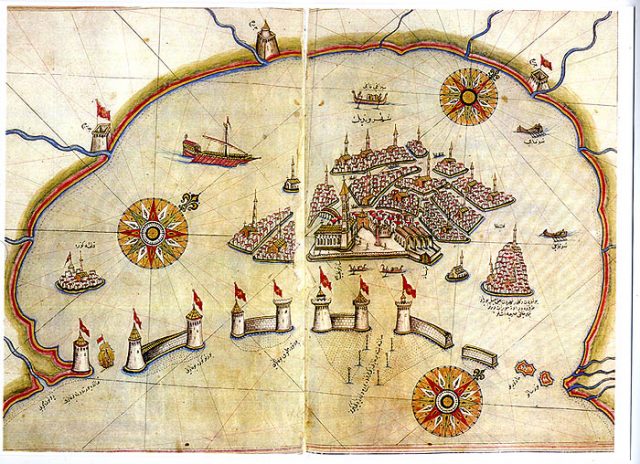

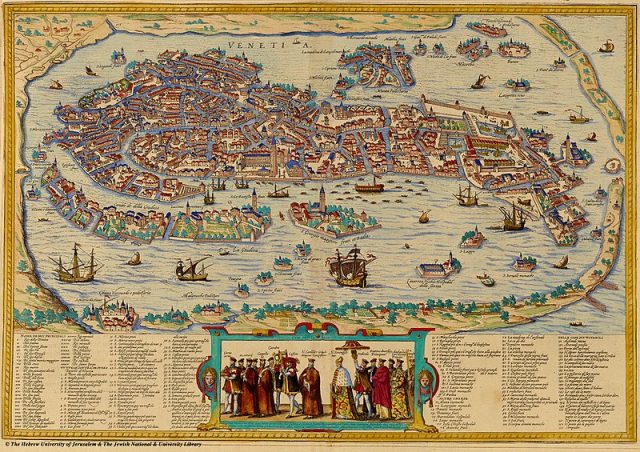

A press release from Dr Toffolo’s stamping ground of the University of St Andrews states, “When Dr Toffolo discovered the image, she realised that the city view of Venice predates all previously known views of the city, excluding maps and portolan charts.” Portolan charts are ancient nautical charts.

She goes on to say the analysis has “great consequences for our knowledge of depictions of Venice, since it shows that the city of Venice already from a very early period held a great fascination for contemporaries.”

The Libro d’Oltramare was previously pored over by Kathryn Blair Moore, who published her findings in 2013’s Renaissance Quarterly. Though Dr Toffolo is the first to highlight the Venice illustration, Moore noted the manuscript’s importance in terms of authorship.

“Although this printed book quickly became the most popular Holy Land guidebook in Renaissance Italy,” Moore wrote, “modern scholars have shown little interest in its historical significance”. Factors driving this view included “its anonymity” and “persistent confusion about its sources”.

Niccolò da Poggibonsi’s credit as author has only been a recent development. Over the centuries his work was reproduced over 60 times under different titles. For example, under a German translation during the 15th century it became the experiences of a certain Gabriel Muffel – the “son of a Nuremburg patrician” writes Smithsonian.

Not that the friar was happy to let his contribution slip into history. He managed to spell out his identity through the first letters of the guidebook’s chapters. His writings were repeatedly re-issued using a pinprick-based technique, where “powder was sifted through the pinpricks onto another surface, thereby transferring the outlines of the image.” (St Andrews)

As da Poggibonsi’s name lives on in perpetuity, his innovations do also. Whereas previous travel accounts would employ classic Latin descriptions, this witness to the world handled the task somewhat differently with a first person style.

Related Article: Little Island in Venice is Considered to be World’s Most Haunted Location

“The genre of Holy Land pilgrimage accounts before the adoption of the vernacular in the fourteenth century was characterized by the repeated copying of previous Latin-language texts,” wrote Moore, “which often resulted in accretive works of unknown or uncertain authorship.”

Thanks to the friar’s skill and clarity of purpose, there is now no confusion as to his identity as author/artist of this remarkable find.