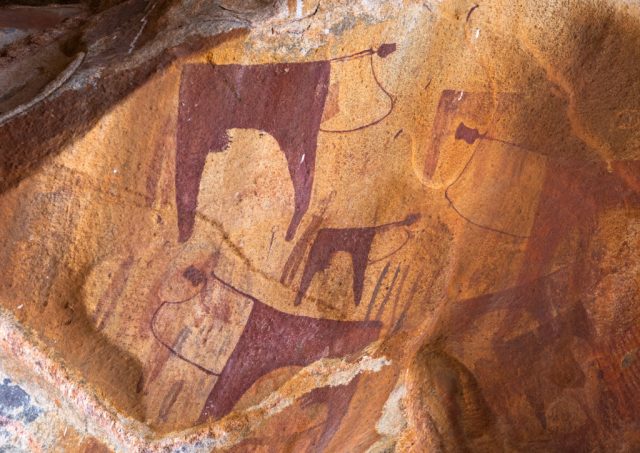

Prehistoric cave paintings are the oldest known form of art, yet little is known about them. The various depictions of men, animals and symbols speak for themselves. But whatever they’re saying, it isn’t much. At least in a modern context.

That doesn’t mean experts don’t have fun trying to work out what they mean, or how they came to be. Initially Europe was thought to be the hotbed of cave painting and figurative – i.e. representational – art. People first stumbled upon this ancient form of expression in Spain.

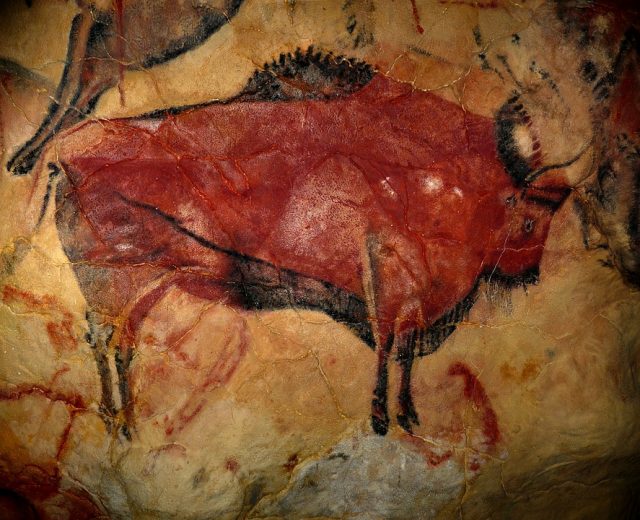

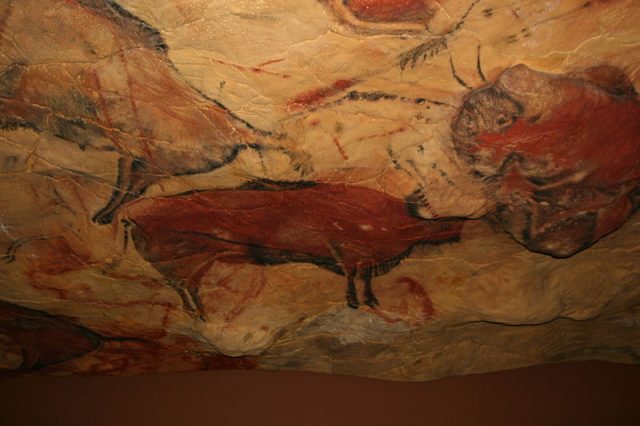

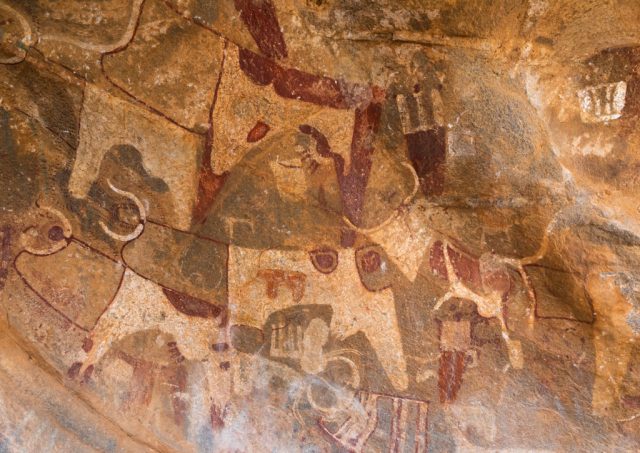

The Cave of Altamira yielded its secret stash of paintings in the late 19th century. Amateur archaeologist Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola discovered renderings of bison – made by the Magdalenian people – which appear to date from between 11 – 19,000 years ago. In fact his little daughter Maria was responsible for pointing them out!

Beacon Learning Center states, “Many of the bison are drawn and then painted using the boulders for the animal’s shoulders. This made them look three-dimensional.” It adds, “These paintings are sometimes called ‘The Sistine Chapel of Paleolithic Art’.”

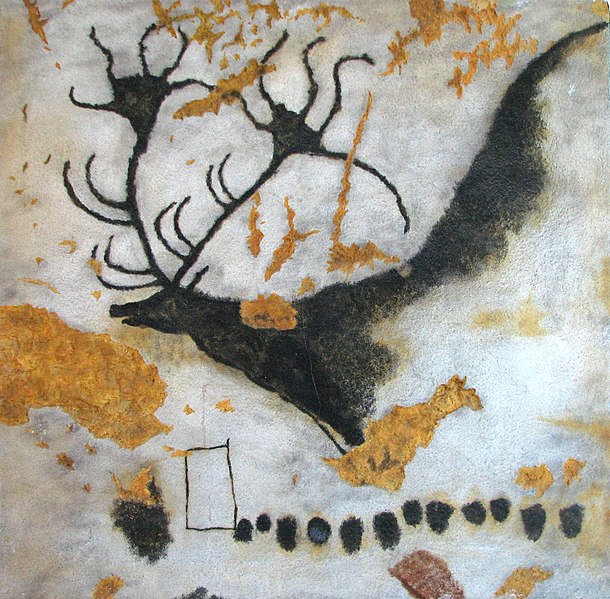

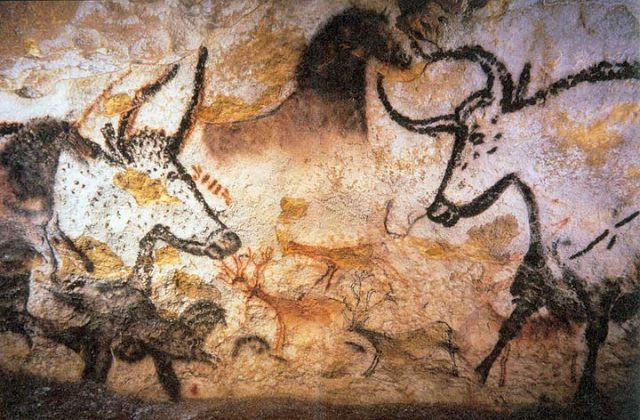

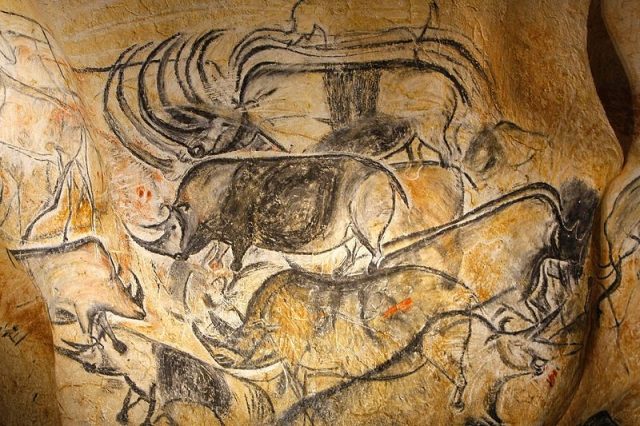

Finds such as these, and those at the Lascaux cave complex in France (again by children in 1940), firmed up the idea that Europe hosted the world’s first artists, unwitting or otherwise. Picasso took a trip to the rocky canvases and marveled at how his work’s origins could be traced back to so-called primitive times. Over 600 paintings have been recorded at this location, and are reportedly 17,000 years old approx.

The painting known as the Chinese Horse, plus its equine companions, is just one of the extraordinary sights that can be seen at Lascaux. Writing about the “Third Chinese Horse”, website Ancient Digger mentions that “The Chinese Horse is more of a myth associated with the Samurai than an actual breed. There are Chinese horses like the Mongolian ponies, which have a likeness to the Third Chinese Horse painting at Lascaux cave, but the evolutionary time frame is completely inaccurate.”

Throw in the fact that the animal appears to resemble a zebra, native to Africa, and the picture becomes confused. When modern interpretation is applied to work dating back thousands of years things are going to get sketchy, so to speak!

Headstuff.org writes, “The usual tools of the art historian’s inquiry – written documentation, knowledge of the social and political climate of the period, and other art and artifacts to use as comparison – do not exist for prehistoric, illiterate societies or are extremely scarce and similarly not understood.”

In terms of literacy, it’s thought visual representations existed before the invention of language. So could ancient peoples have been speaking their mind when daubing those rock faces?

Comparisons are frequently made with modern day hunter-gatherers, who live their lives according to ancient traditions. This line of thought naturally brings belief systems into the mix. When assessing prehistoric cave paintings, doesn’t it stand to reason that religion plays a part?

Headstuff notes, “it is possible that cave art served as a kind of record of the mythologies and histories of tribes, their rituals… The figural imagery may have recorded a narrative, while the abstract symbols could have indicated records of a more symbolic nature.”

The case of charcoal illustrations found at Chauvet Cave in France highlight the challenges not only in determining what these artists intended, but when they actually made the paintings. “Radiocarbon dating, the kind used to determine the age of the charcoal paintings at Chauvet, is based on the decay of the radioactive isotope carbon-14 and works only on organic remains,” says Smithsonian.com. “It’s no good for studying inorganic pigments like ocher, a form of iron oxide used frequently in ancient cave paintings.” Just one complex factor in a baffling area of archaeology.

Relatively recent assumptions about sophisticated types of cave art being from later than their cruder counterparts has also led researchers up a blind alley. It seems artistic understanding can’t be pinned down. Think of the boulders used to show the bisons’ dimensions at Altamira. Who knows where true inspiration struck when it came to putting primitive paint to rock?

“The colours, scale, perspective, shading or lack of, naturalism, and detail in many cave paintings vary from simple, monochromatic line drawings to complex, three-dimensional images rendered naturalistically and in several colours,” writes Headstuff.

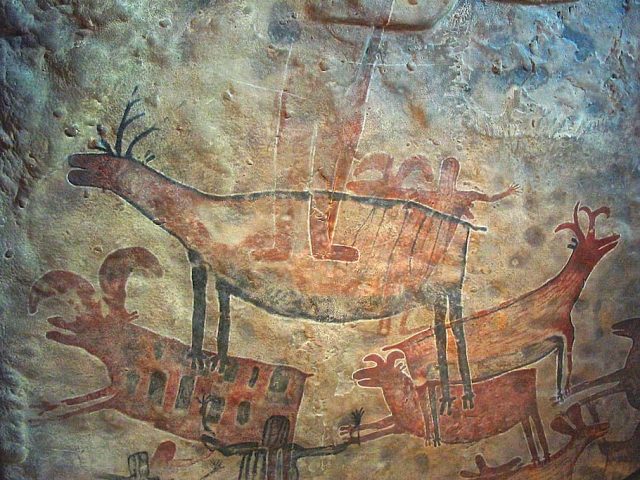

The latest news about prehistoric cave paintings was broken only last December. The Indonesian island of Sulawesi revealed art going back over 44,000 years. It also breaks the pattern away from Europe. A team from Griffith University in Brisbane have uncovered what’s described by Nature.com as “the oldest figurative artworks — those that clearly depict objects or figures in the natural world — on record”.

Like many other examples, the find was made by accident. “A team member named Hamrullah, who is a Sulawesi-based archaeologist and caver,” writes Nature, “had found the paintings after shimmying up a fig tree to reach a narrow passage at the roof of another cave.”

Thought to depict the hunting of pigs and buffalo across a 4.5 m long panel, the images are being analyzed through the study of “popcorn” calcite (a mineral), which has grown over the surface. It isn’t a foolproof method of testing, but as technology advances, so does the insight into ancient culture.

Related Article: Mysterious 45,000-yr-old Cave Art Depicts Mythical Part-Human Part-Animal Beings

Prehistoric cave paintings may never tell their story, if indeed they are narratives of a historical nature at all. Whether primitive doodles or intelligent design, they will continue to grab the attention for centuries to come.