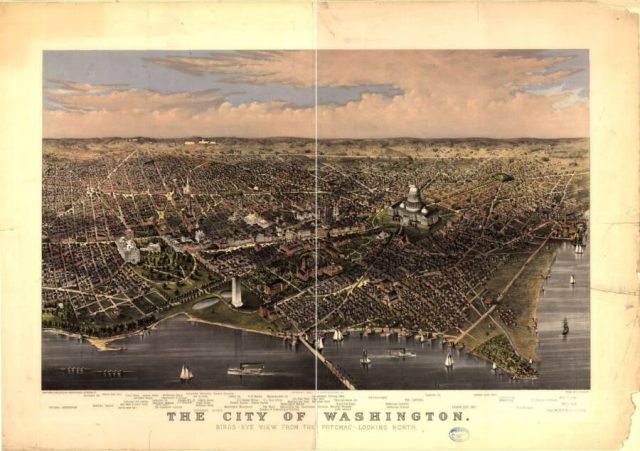

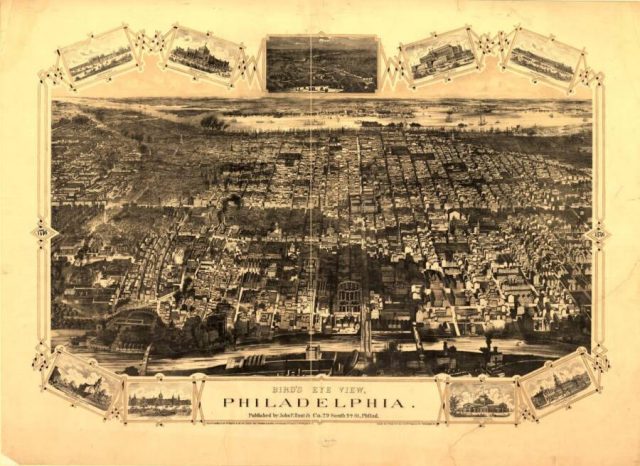

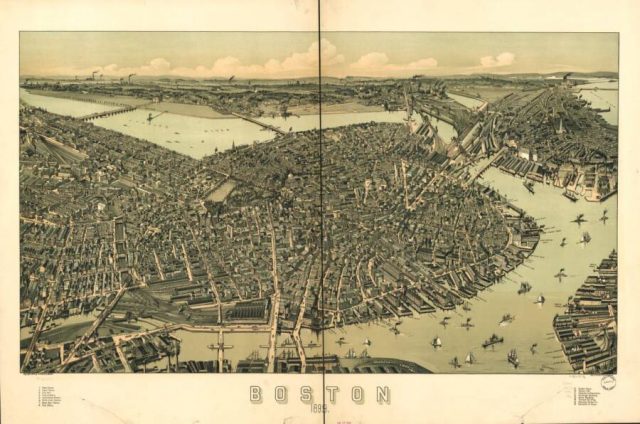

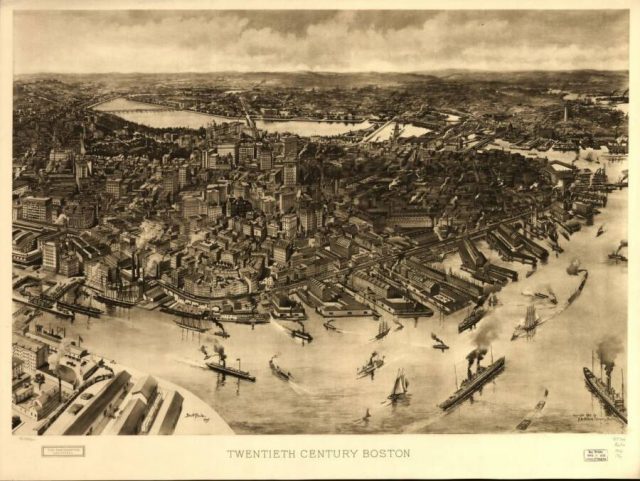

Long before Google started offering aerial maps of the world, there were vintage “hot air balloon” maps. People were still interested in having a birds-eye view of things. During the Victorian era that interest spawned the development of so-called panoramic maps, which became a popular method to give people a look at various cities in America and Canada, according to World Maps Online.

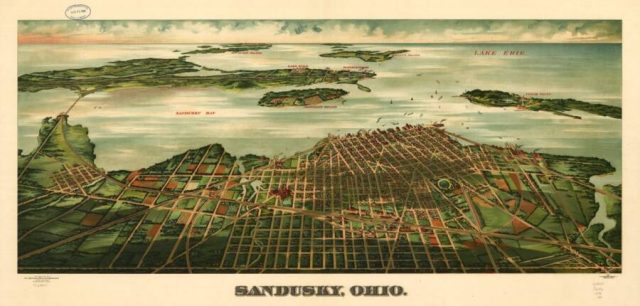

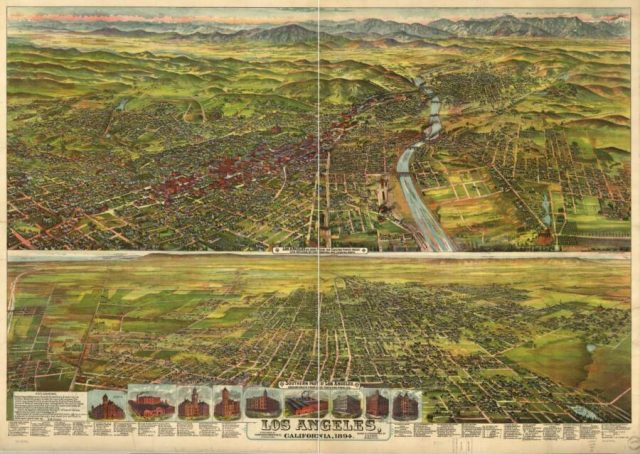

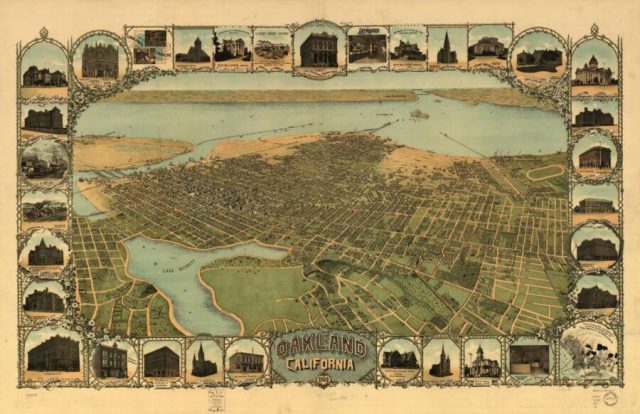

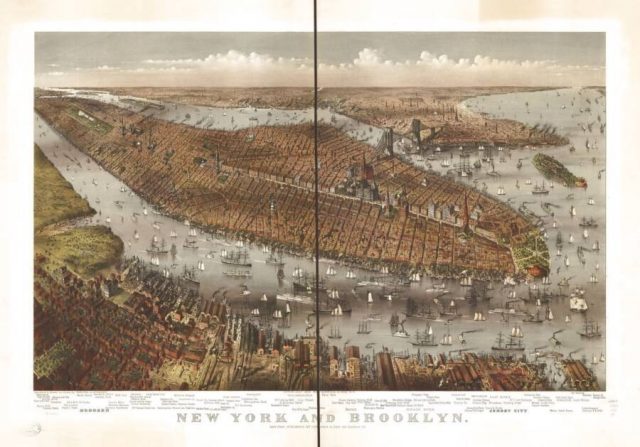

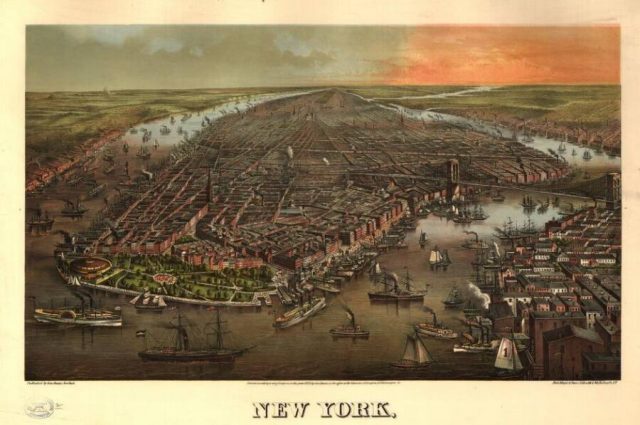

The maps had a variety of names. They’ve been called panoramic maps, bird’s eye views, aero views, perspective maps, and even balloon maps, since artists would sometimes use hot air balloons to get the perspective they needed for their creations. Each of those names refers to a type of map that wasn’t photographic and might not be drawn to scale, but still showed a view of a particular city or area from above, at an oblique angle. Such maps had illustrations of the layout of a particular areas, including natural features and roads, but also including the various buildings, parks, etc., that could be seen from the point of view of the person producing it.

The Library of Congress has a large collection of the maps, holding about 1500 different examples of the form. Of the maps in their collection, more than half were produced by the same five artists, Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler, Henry Wellge, Oakley H. Bailey, Albert Ruger, and Lucien R. Burleigh.

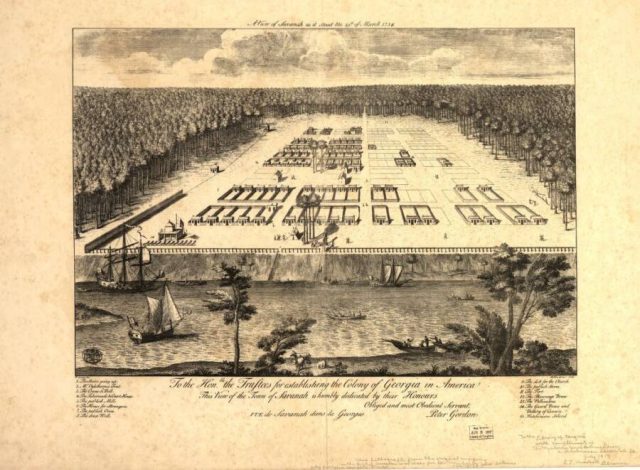

A website dedicated to vintage city maps notes that although panoramic maps were popular between the 1840s and the 1920s, the idea wasn’t a new one at the time. The idea of perspective mapping first became popular in the late 1500s and early 1600s, in Europe. At the time, the drawings were usually of small towns by modern standards, and the focus was usually on the governmental or commercial center, with the rest of the town spreading out around it.

The drawings were often meant to be included in book like atlases or geographical books. Those maps were generally drawn from a low angle and typically didn’t name any of the streets that were depicted. Sometimes the same perspective might be used to represent several different European cities.

The idea of perspective mapping was first used in the US before the Civil War. Similar to their European counterparts from the Renaissance, the early American maps were usually showing views from a low angle, and sometimes even from ground level. Often the pattern of streets wasn’t very distinct. Creating the maps was extremely labor intensive.

After building a ‘frame’ which showed the perspective of the streets that were going to be included, someone had to walk all those streets taking in all the relevant buildings and features, right down to the landscaping. Once all the basic information had been gathered, the artist then had to render it as it they thought it would look from high overhead.

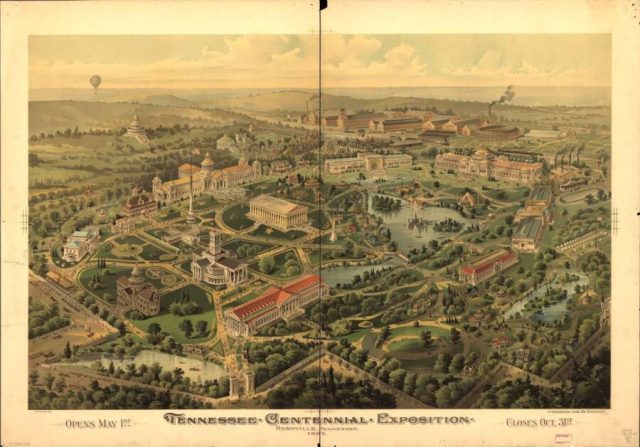

It wasn’t until the post-Civil War era that the nature of panoramic maps really began to change. The maps became more accurate and detailed, and the ‘views’ came from higher up. It became more common to see maps showing smaller towns, as well as larger urban areas. During this time, maps were no longer meant for inclusion in atlases, but became desirable as independent images in their own right, even being endorsed by local chambers of commerce as a source of pride in one’s town or city.

In addition to showing an area as it presently existed, the vintage maps began to also include surrounding areas that were meant for future development. That way, they could serve as lures to prospective land developers and business people as a way of attracting investment. Artists paid for the production of the maps by soliciting subscribers, who would then have their home, church, business, or school included in the rendering.

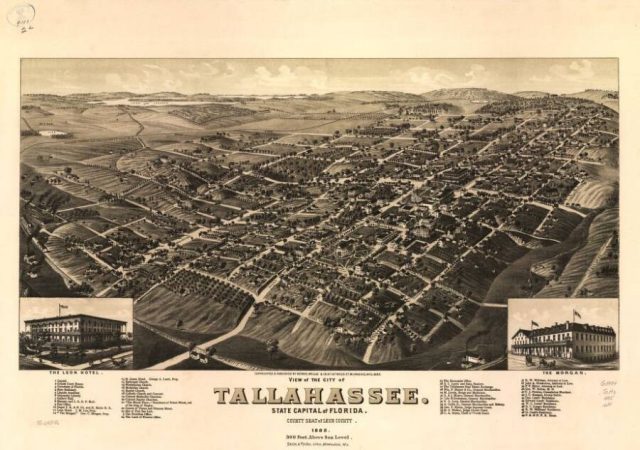

At that period in time, panoramic mapping was nearly unique to America. Even within that context, there are far more representations of northern and western cities than there are of Southern towns from the same era. Not only were cities faced with the expenses of reconstruction often too financially strapped to afford such complicated and expensive undertakings, most of the artists who produced such images were from the North, and not likely to be particularly welcome below the Mason-Dixon line.

Related Article: Oldest Known Illustration of Venice Discovered in 14th Century Travelogue

The trend for panoramic vintage maps continued until well into the 1920s, which isn’t really a surprise, as advances in related technology involving printing and photography allowed them to become increasingly detailed and beautiful. Even today, prints of various old maps of places like Paris, San Francisco, London, and New York can be found in any number of retail outlets, framed as wall art.