Pandemics have the power not only to end lives but change history. There are terrible examples that show people responding to such threats across the ages. These dark chapters make for scary reading, yet they’re also vitally important. By finding the means to stop them, doctors learned valuable and life-saving lessons.

Here’s how humankind endured history’s worst outbreaks and ultimately survived…

Early infections

The world is better prepared for an aggressive pandemic than it was in the past. A reassuring, if grim, fact! Ancient civilizations were caught unawares by the nastiest of infections.

The Great Plague of Athens in 430 B.C. not only ravaged the population, it also happened during a conflict. The earliest recorded pandemic spread against the backdrop of the epic Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 B.C.). Fought between the Athenians and the Sparta, it had already been raging for over a year when nature stepped in. History.com describes symptoms like “fever, thirst, bloody throat and tongue, red skin and lesions.”

The plague then impacted on the war’s outcome. The Atlantic writes, “there is little doubt that the Great Plague changed the course of the war (being at least in part responsible for Athens’s defeat) and significantly shaped the peace that came afterward, planting the seeds that would weaken and then destroy Athenian democracy.”

The nightmare went on for 4 years. As for what the plague was in the first place, smallpox, typhus and bubonic plague are amongst the suspected diseases.

Quarantine is coined

Words like isolation and quarantine are in common use at the moment. But where did the whole idea come from? It took a while before the penny dropped. The Plague of Justinian (541 to around 542 A.D.), Black Death (1347 – 1353), and the Great Plague of London (1665 – 66) may seem like separate events. They were actually manifestations of the same disease. Plus, these three dramatic periods are only a fraction of multiple plague outbreaks over the centuries.

Named after Roman emperor Justinian I, the original plague was transported via grain offered in tribute to the unfortunate ruler. Black rats hitching a ride with the foodstuff were in turn being munched on by plague-packed fleas. They inadvertently ravaged Constantinople, with as many as 50 million thought to have died across several continents. The bacteria behind this most persistent of pandemics is ‘Yersinia pestis’.

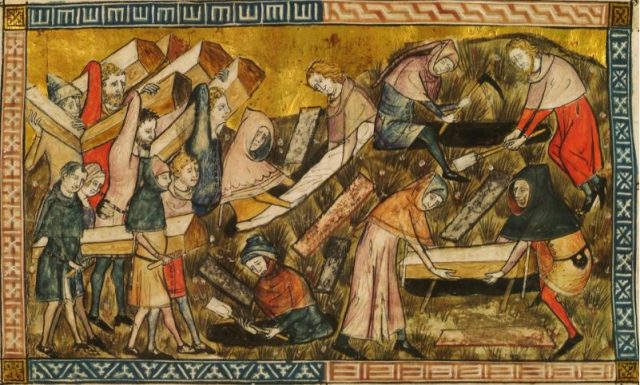

Arguably the most well known version of the plague was Black Death. Symptoms include abdominal pain, fever and gangrenous skin. On its arrival in Europe, the sickness took a recorded 200 million within several years!

Ragusa in southern Italy was a city with a busy port. Venetian traders heard of an isolation method practiced by Ibn Sina, a scholar of medicine from Persia who believed microorganisms were responsible for illnesses. So when Ragusa’s officials heard of this through the traders, they made the simple but effective decision to lock off and monitor visiting sailors. “At first, sailors were held on their ships for 30 days, which became known in Venetian law as a trentino” writes History. “As time went on, the Venetians increased the forced isolation to 40 days or a quarantino, the origin of the word quarantine and the start of its practice in the Western world.” Sources state that Sina’s method was called “al-Arba’iniya, or “the forty”.

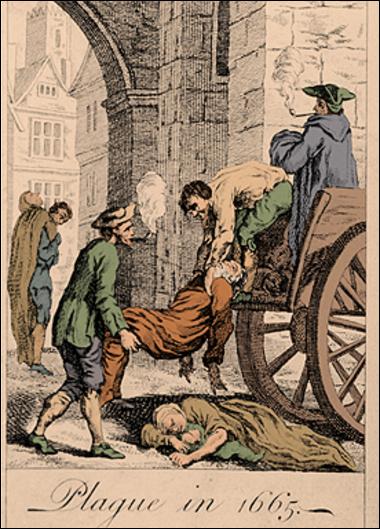

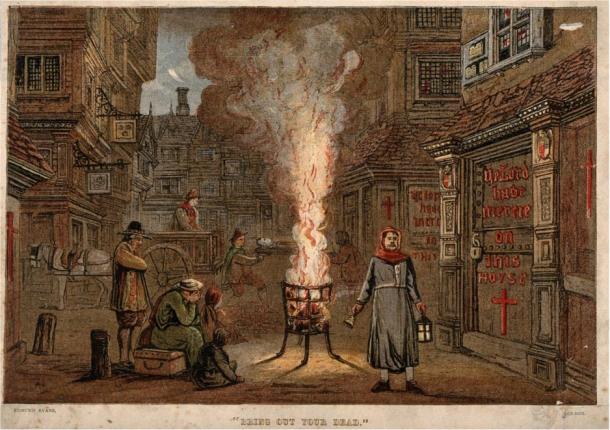

When the Great Plague of London hit, it was the culmination of a long and harrowing time for England’s capital. The place was no stranger to Black Death, and it must have seemed so cruel that the latest attack killed 100,000 inside 7 months! Again, fleas played a key role in the spread.

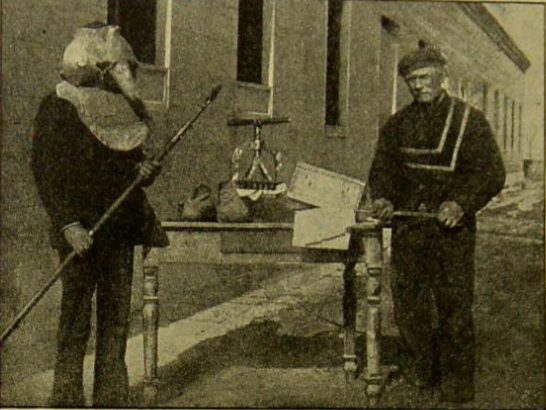

By this stage, the English were accustomed to isolating people in their homes. In a familiar-sounding measure, public venues were shut. Though things were certainly more intense back then – red crosses were daubed on doorways, and if someone walked down the street carrying a white pole it meant they lived in a plague-ridden household.

The Great Plague was then interrupted by another force of nature. Live Science notes while the disease “spread rapidly through the hot summer months”, that heat was intensified when “On Sept. 2, 1666, the Great Fire of London started, lasting for four days and burning down a large portion of the city.”

Arrival of Vaccines

Following many agonizing centuries, people were growing more aware of how to tackle a pandemic and illnesses in general. Keeping a distance was long-established. However the first vaccine wasn’t devised till 1796.

Dr Edward Jenner from Gloucestershire, England changed the game for sufferers of smallpox. The virus had seemingly dogged humanity forever. Fever, head pains and blistering were just accepted parts of day to day life on a pre-vaccinated planet.

When Europeans set sail for the New World, they spread the disease even further. History quotes Prof Thomas Mockaitis of De Paul University, who remarks “There hasn’t been a kill off in human history to match what happened in the Americas”. Around 10 million are thought to have lost their lives.

Dr Jenner owed it all to udders! In the countryside, he observed that milkmaids had a resistance to smallpox. What was peculiar about them was they carried their own affliction, in the form of cowpox. By giving people cowpox – and notoriously using a 9 year old boy as a test subject – Jenner inoculated them against the bigger beast. By 1980 the dreaded pandemic was off the map.

Improved Sanitation

Quarantine and medicines were beginning to meet pandemics head on. But another piece of the puzzle was yet to be put in place – public health. During the first half of the 19th century, cholera went on the warpath in England. Watery bowels, vomiting and looser skin made this affliction far from manageable. What was causing it? There was something in the air, according to experts of the day.

Dr John Snow of York didn’t trust the famous theory of a “miasma” invading people’s bodies. He suspected the water supply. It would be some years before Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about the world’s greatest detective. In some ways, Snow was a forerunner as History explains.

“Snow acted like a scientific Sherlock Holmes,” the site writes, “investigating hospital records and morgue reports to track the precise locations of deadly outbreaks. He created a geographic chart of cholera deaths over a 10-day period and found a cluster of 500 fatal infections surrounding the Broad Street pump, a popular city well for drinking water.”

Related Article: History’s Worst Pandemic – How the Spanish Flu of 1918 Infected America

By removing the pump handle, cholera’s flow was well and truly stemmed. The disease wasn’t eradicated altogether, but at last there was some insight into this merciless pandemic. All the cases described here have led up to the current and frightening situation the world is in now. Doctors and scientists follow in the footsteps of Jenner, Snow and all those seeking to put an end to pandemics and the destruction they wreak…