A giant wombat is changing the way people see wildlife Down Under. Not that it exists today – this marsupial is millions of years old and has turned up in fossil form.

Dubbed “Mukupirna nambensis”, the New York Times describes it as “a mega-wombat that tipped the scales at well over 300 pounds.” It has been compared to a black bear and is reportedly 5 times bigger than the average wombat. “Mukupirna” is from the Aboriginal languages of Dieri/Malyangapa, translating as “big bones”.

The new and exciting discovery of the giant wombat remains is believed to be one of the oldest examples of a “vombatiform”. Today’s wombats and koalas are descended from this varied group of ancient animals. The creature was found in the Lake Eyre Basin in South Australia.

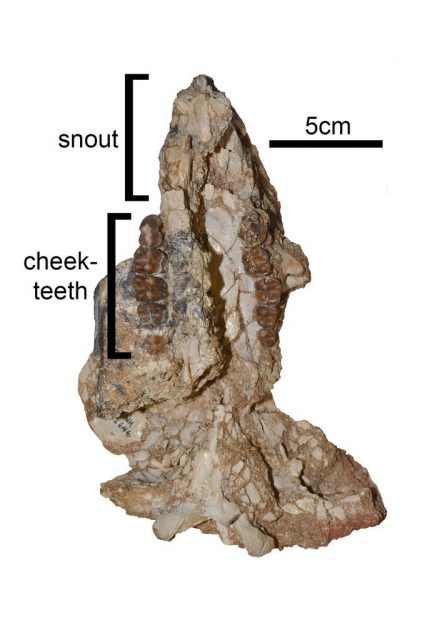

The mighty marsupial lived 25 million years ago, roaming lush rainforest during the Oligocene period. Researchers led by Dr Robin Beck of the University of Salford examined fossilized remains, comprising most of a skeleton plus partial skull. Their analysis is published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Noting the skull’s teeth bore similarities with baby wombat gnashers, they made the connection to this intriguing slice of natural history. “For millions of years up to the present day, big, unique marsupials flourished on Australia and New Guinea, isolated from the rest of the world” writes the Times. However lack of fossil evidence has created a sense of mystery, a veil which has been lifted slightly in recent days.

Another factor is the time taken to study Mukupirna nambensis in the first place. The remains were actually uncovered in 1973. Packed in plaster, it crossed oceans to sit on the shelves at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Now in the 21st century Dr Beck has produced high resolution images, giving the extraordinary specimen the coverage it deserves.

Quoted by Science Focus, team member Pip Brewer of the Natural History Museum says the find displays “a fascinating mix of characteristics”, providing “evidence of a close link between wombats and an extinct group of marsupials called wynyardiids.” The find confirms that wombat digging and burrowing habits evolved over time, and from an early stage. Beforehand, this was just a theory.

It was “also found the animal’s arms would have made it an efficient digger, allowing it to scratch around for roots and tubers,” writes the Times, “although it probably would not be able to burrow like modern wombats.”

The 1973 team used metal rods, which they pushed into the clay in search of solid objects like fossils. Mukupirna nambensis wasn’t the only animal ancestor down in the dirt. “Nearer to the surface, they uncovered and later published an alien ecosystem” says the Times. Fascinating material like “teeth from lungfish, possums and freshwater dolphins; bones from flamingos, kangaroos that galloped instead of hopping and a supersized koala, among others.” If a giant koala existed, one would hope it only ate eucalyptus leaves.

Investigating this eye-widening wombat is only the latest stage in a long-standing archaeological puzzle. Writing in Scientific Reports, the experts admit “a number of key questions remain unresolved, particularly regarding the origin and interfamilial relationships of vombatids.”

That said, they are hopeful for the future. The epic marsupial “provides key new data for understanding the evolutionary history of vombatiforms, including the evolution of digging adaptations”. It’s also a scientific treasure trove in relation to teeth structure and other biological information.

Related Article: Fossils of an Enormous Turtle the Size of a Car Found in South America

One detail wombats are renowned for is their habit of producing excrement in the shape of cubes. Naturally reporters are interested to find out if this was the case with Mukupirna nambensis, though results are not forthcoming as yet. If that turns out to be the case, then it will be one major scoop.

Steve Palace is a writer and comedian from the UK. He’s a contributor to both The Vintage News and The Hollywood News and has created content for many other websites. His short fiction has been published by Obverse Books.