An ancient salt excavation, Provadia-Solnitsata, is a thirty two acre area within the Mirovsko salt deposit near the town of Provadia in northeastern Bulgaria and is believed by archeologists to be the oldest salt production site in Europe dating from between 5500BC and 4200BC.

Salt was very important before refrigeration was invented and from the ancients right up to the 1700s people kept their salt locked away.

Roman soldiers were sometimes paid in salt. Used as a flavor enhancement in modern times, salt has been used to dry and preserve food for thousands of years.

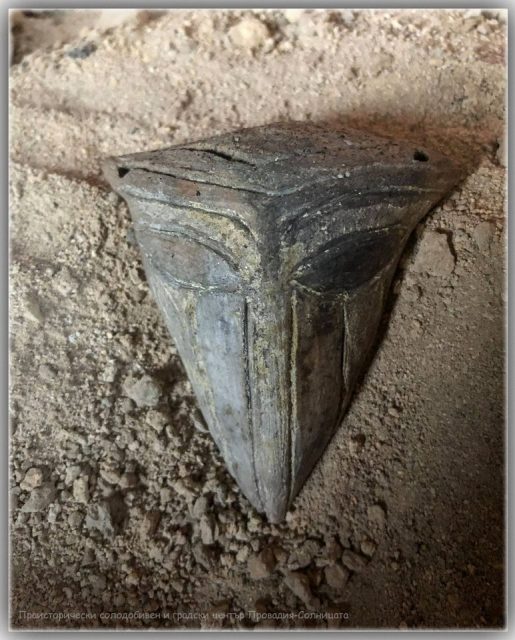

Recently, an artifact believed to be a representation of a salt god was unearthed at the excavation. It is a triangular shaped ceramic head with ears and eyes but no mouth. As with most unusual discoveries there are those who cry “aliens” but only the news crews who make a living exaggerating fact believed this.

There are some scientists that believe it may be a portrayal of Salacia, the Roman goddess of salt water and the sea.

According to his research paper at journals.openedition.org, Vassil Nikolov, Professor Emeritus of the Institute of Archeology and Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences tells us Provadia-Solnitsata was also the first prehistoric urban center dating back to 4700BC and it was protected by a fortified wall around a stone citadel that included a necropolis and sacrificial pit.

A huge salt cone was formed when pressures from the earth shot the salt into the air and it was protected by marl to keep it fresh.

Salt makers in Neolithic times produced so much that there was plenty for the locals and the surplus was used for trade south of the Balkan Mountains. Nikolov, who still works at the site, claims it is “the most significant prehistoric site in Southeastern Europe.”

According to latimes.com, the city had only about three hundred and fifty people and some were extremely wealthy from the salt trade.

A cemetery in nearby Varna attests to this as there were thirteen pounds of gold recovered from graves in only one cemetery.

Some graves were rich in artifacts of gold bracelets, earrings, breastplates, rings and small votives. Other graves had barely a few beads, bone jewelry and a few flint knives showing the inequality of wealth just as today.

The citadel (or tell) includes layers of stone all the way back to the Late Neolithic Period and the Romans added a burial mound. Solid stone walls surrounded the tell to protect the valuable salt.

The most recent excavation has been studied by archaeologists since 2005 and so far, they have found about thirty ritual pits about two hundred feet to the west of the tell and another to the northeast with a mass grave of those who suffered a violent death in the unrest caused by the disappearance of the salt springs in the late 5th millennium BC during a probable drought.

Other graves have been found with the usual skeletal remains but some were found with cow skulls, copper and bone tools, copper axes, jewelry and many different types of pottery.

In one grave the remains of a woman and two small children were found. Many were found in fetal positions, especially the children, according to www.ancient-origins.net

The ancient Bulgarians boiled brine water from the springs containing about one hundred and sixty to one hundred and ninety grams of salt per liter in ceramic bowls placed in large clay dome ovens to extract the salt. Once the moisture was extracted what was left was a perfect block of salt ready for market.

Production was a twenty four hour job and according to provadia-solnitsata.com, over two thousand pounds were extracted in a year. Over the years, earthquakes have destroyed much of the ancient city and the walls that protected it.

Another Article From Us: Is This the Childhood Home of Jesus Christ, Archaeologists Believe So

The earliest salt makers worked in their own homes but as demand grew production centers were built just out of town making the process faster and more profitable.