Medieval times were tough. Archaeologists in Cambridge England have built a fascinating yet harsh picture of life between the 10th – 14th centuries.

How so? By examining battered – and in some cases shattered – medieval bones. “Back breaking work” is an expression particularly suitable for medieval times! Awful employment opportunities included labouring in town or toiling in the fields.

The University of Cambridge wanted to research “physical distress visited upon the city’s inhabitants by accident, occupational injury or violence during their daily lives” according to EurekAlert.

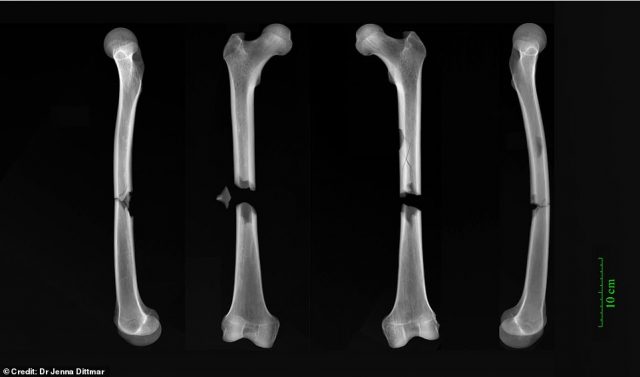

314 sets of remains were analyzed using x-rays. The skeletons needed to be at least 25% intact and over the working age of 12.

Led by Dr Jenna Dittmar, the findings are published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Several hundred years ago the hallowed city and seat of learning was “primarily a provincial town of artisans, merchants and farmhands”. This is noted by BBC News, who add scholars became part of the culture in 1209.

One conclusion of the study is that those at the bottom of the heap had it worse. Close to half of Cambridge’s working class population broke 1 bone or more. Fairly obvious given the tough existence associated with the period.

But there’s more to the research than saying poor people were treated appallingly. Dr Dittmar and co highlighted 3 locations of interest in the area.

The All Saints by the Castle parish cemetery was a place where “ordinary” folk received a burial. 84 skeletons went under the scanner, from excavations going back to the 1970s.

Secondly, the former Hospital of St John the Evangelist and its grounds. These were sheltered individuals, disabled or infirmed and in need of care. Excavated in 2010, 155 souls came from there.

EurekAlert draws attention to “corrodians”. These were elderly residents who retired to the Hospital and lived in a medieval care home-style environment.

Thirdly, the Augustinian Friary, dug up in 2016. This was reserved for clergymen and wealthy benefactors wishing for a blessed burial. 75 sets of bones were used for the study.

Dr Dittmar’s team took care to look at different levels of society. Hardship may have favored the have-nots, but sometimes the haves had a bad deal. Quoted by BBC News, she says “severe trauma was prevalent across the social spectrum.”

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the worst example, the sorry remains of a friar. He suffered 2 snapped femurs, which almost certainly resulted in his demise. What caused the agonizing blow? “Our best guess is a cart accident” Dr Dittmar told The Times. The result is also compared to being hit by a car.

In another case, a friar had fractured lower arms and head wounds. By the looks of things, the highly regarded victim was attacked and tried to defend himself.

Evidence exists of domestic violence, going by modern day assessments of the injuries involved.

In terms of percentages, working class figures are stark. 44% of the hardest hit lived with broken bones. 40% of men and 26% of women had fractures. Surely contributing factors to the average lifespan of just 31.

Dr Dittmar is connected to “After The Plague”, a research project exploring that mother of all medieval health issues the Black Plague (1347 – 50).

As stated on its website, the project concerns “consequences not accessible through historical sources”. The examples of post-plague wage rises and improved nutrition are highlighted. Did these go hand in hand, or was increased prosperity not matched by better standards of health?

Studies such as this wide-ranging examination of medieval bodies should provide important data.

Another Article From Us: Incredible – McDonald’s Opens Restaurant Which Includes an Ancient Roman Road

It’s difficult to fully imagine what life would have been like in medieval times. However one thing is clear – people needed to watch their backs, from the lowly peasant to the unsuspecting authoritarian. A careering cart, a vengeful mob… seems there were too many ways to die hundreds of years ago.