Louisa May Alcott is perhaps best known for penning the novel Little Women, but she also wrote a short satire called Transcendental Wild Oats. This story gives a stark insight into the time she spent as a child at Fruitlands, a commune that lasted only seven months.

Fruitlands is born

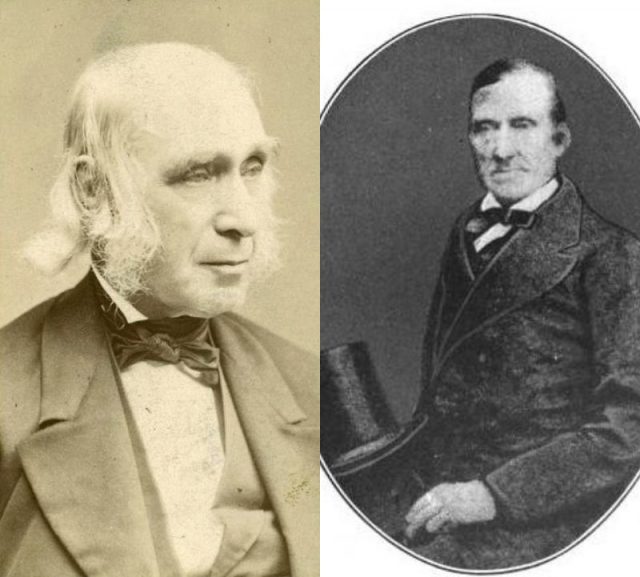

The Utopian society of Fruitlands was the brainchild of Amos Bronson Alcott (Louisa’s father) and Charles Lane.

The two men met in England in the 1840s, and Lane traveled back to the USA with Alcott. Not long after, in May 1843, Lane purchased Wyman Farm in Harvard, Massachusetts. The property consisted of 90 acres (36 hectares) with a dilapidated house and barn and 10 apple trees and was renamed Fruitlands.

The commune of Fruitlands was based on transcendentalist principles. This movement believed that people are inherently good but become corrupted by society and the economy in particular. In total, there were 14 residents including the Lane and Alcott families, all of whom believed in “simplicity in diet, plain garments, pure bathing, [and] unsullied dwellings.”

In an effort to distance themselves from the world’s economy, they owned no personal property, recruited no hired labor, and didn’t partake in trade. Fruitlands was intended to be completely self-sufficient.

A Day in the life

All the residents were vegans who drank only water. Linen clothes and canvas shoes were the order of the day since no leather was allowed. Even artificial light was banned because the oil used at the time was derived from an animal.

No animal labor was used because those at Fruitlands believed animals were less intelligent than humans. Consequently, it was humanity’s duty to protect animals. In addition, because of their lesser nature, the labor of animals would taint the cleanliness of all other human endeavors if they were used on the farm.

Alcott and Lane even went so far as to prohibit carrots, beets, and potatoes, since these were seen as having a lower nature because they grew downward.

Fruitlands in Decline

By July, only 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of grain, one of vegetables, and one of melons had been planted. The commune members had already been a month behind the normal planting schedule when they arrived, and this delay wasn’t helped by the fact that many of the men spent their time philosophizing rather than tending the fields.

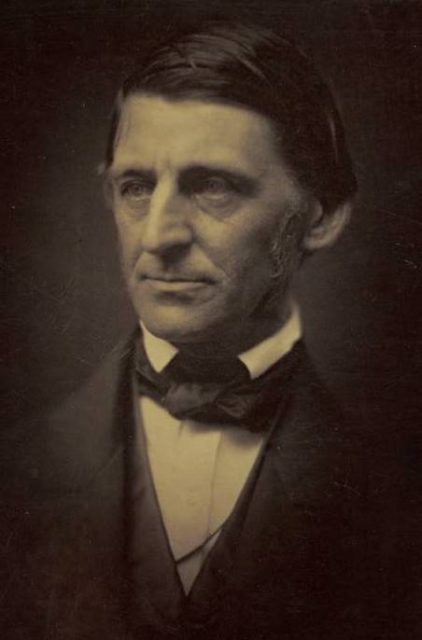

The American philosopher and essayist Ralph Waldo Emmerson visited Fruitlands in July. He was inspired by what he saw but anticipated problems in the future: “They look well in July. We will see them in December.”

His words were prophetic since, seven months after the adventure had begun, Fruitlands was abandoned due to a lack of food and growing unrest among the members. The Alcotts abandoned the property in January 1844.

Transcendental Wild Oats: A Chapter from an Unwritten Romance

Louisa May Alcott’s short piece was first published in a newspaper in 1873 and describes her time at the commune.

The piece begins in a very uplifting manner, describing the arrival of people at the farm: “A serene man with a serene child upon his knee was driving” while another boy sits there “firmly embracing a bust of Socrates.” One woman has “eyes brimful of hope and courage” while two little blue-eyed girls are “chatting happily together.” Even when it rains, their moods aren’t dampened.

But the wit and wry descriptions make it clear that this is a mission doomed to failure. She paints a comic and, at times, almost unkind picture of the “Brethren” who are forging a new life.

Brother Timon crunches a fallen mirror in his stride while remarking, “We want no false reflections here.” Brother Abel is later described as “blissfully basking in an imaginary future as warm and brilliant as the generous fire before him,” while Brother Lion becomes “Dictator Lion” as he spouts principles.

Speaking about the decision not to use animals, Louisa writes that while “such farming probably was never seen before since Adam delved,” it ends up that “a few days of [digging] lessened their ardor amazingly.” She describes how vegetables were planted but, because manure was not allowed, very few of them grew.

As well as relating how they live, Louisa also describes the members themselves in comic detail. “Each member was all allowed to mount his favorite hobby and ride it to his heart’s content. Very queer were some of the riders, and very rampant some of the hobbies.”

Louisa was not exaggerating, since residents at the farm included Samuel Larned, who believed that foul language spoken honestly could be uplifting; Joseph Palmer, who had gone to prison for defending his right to grow a beard; and Abraham Everett, who had been in an insane asylum prior to joining Fruitlands.

The character of Forest Absalom is described as helping Sister Hope (Louisa’s mother) with her work and doing “the many tasks left undone by the brethren, who were so busy discussing and defining great duties that they forgot to perform the small ones.”

This is in reference to the fact that Alcott and Lane would spend so much of their time teaching and philosophizing that they’d neglect some of the crucial work of the farm. In one diary entry, Louisa notes how the women and girls had to race in and collect the barley before a thunderstorm because the men had cut it but left it lying in the field.

When describing the decline of Fruitlands, the story focuses on Brother Abel (who represented her father): “He had tried, but it was a failure. The world was not ready for Utopia yet, and those who attempted to found it only got laughed at for their pains.”

With sadness to her tone, she notes that while others in years past might have given everything they had to the poor and be honored when they led holy lives, “in modern times these things are out of fashion.”

At the conclusion, Brother Abel gives up and lies down on his bed, refusing all food and water. In real life, her father did this too. But the story itself has an uplifting ending, if not a happy one.

As he lies there with his back to the world, Brother Abel reflects on the fact that his wife and children have not abandoned him. He recognizes that he owes them a duty to rise and help them escape the burden that Fruitlands has become, and so he does.

They leave together for a neighboring farm. As they pass the orchard, a frost-bitten apple falls from a tree, and Abel mourns: “Poor Fruitlands! The name was as great a failure as the rest!” His wife, with both tenderness and satire, replies, “Don’t you think Apple Slump would be a better name for it, dear?”

Fruitlands Today

After the commune fell apart, Joseph Palmer, one of the Fruitlands members, kept the farm going and made a go at another commune there. After that, the property was purchased in 1910 by Clara Endicott Sears, who opened it as a museum in 1914.

She also brought together essays written over the years about Fruitlands and the diaries of Louisa and her mother. She published them in a book entitled Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands, listing herself and Louisa May Alcott as the authors.

More from us: The Grapes Of Ruff: John Steinbeck Wrote A Werewolf Novel

Today, part of Fruitlands Museum includes a museum on Shaker life, housed in a Shaker building that was transported from nearby Harvard Shaker Village. The Shaker way of life was very similar to what Alcott and Lane tried to implement at Fruitlands, but it is less rigorous and allowed for the trade of homemade goods for tea, coffee, and other items.

The Fruitlands farmhouse is now a National Historic Landmark and is restored to how it would have looked in the 1840s. There is also an art gallery and a museum of Native American history.