For many in the criminology field, the mid-to-late 20th century is viewed as being the height of the serial killer epidemic. While many studies focus on the United States, there were serial murders being committed in the United Kingdom. One British serial killer was Peter Sutcliffe, who from 1975-80 was known as both the “1970s Jack the Ripper” and the “Yorkshire Ripper.”

The makings of a killer

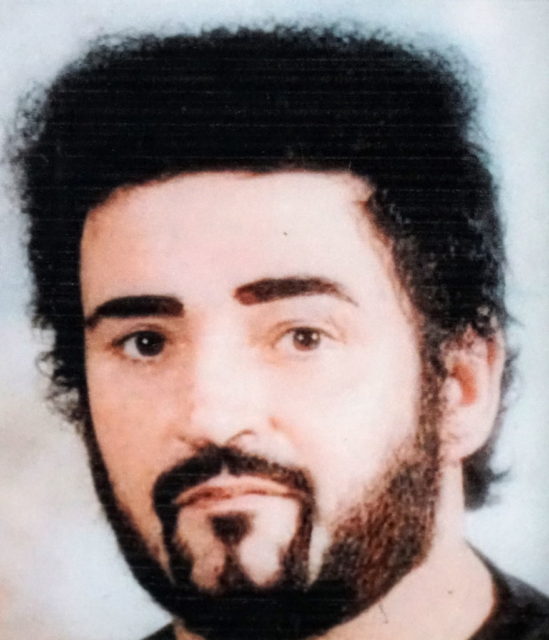

Peter Sutcliffe was born to a working-class family in Bingley, Yorkshire. He left school at fifteen and held a variety of jobs, including work at a factory, as a gravedigger and at a local morgue. In 1974, he married Sonia Szurma, and a year later obtained work as a heavy goods truck driver.

Growing up, Sutcliffe showed many of the hallmarks of a serial killer in the making. While the majority refer to the MacDonald triad – fire setting, bedwetting and animal cruelty – there are other indicators. One is a person’s home environment. According to one of Sutcliffe’s brothers, their father was an abusive drunk who regularly whipped them with a belt. In one instance, he smashed a beer glass over Sutcliffe’s head.

He was also a loner, and after beginning work as a gravedigger developed what those around him called a “morbid” sense of humor. After starting work at the morgue, he bragged to his friends about robbing bodies. Finally, there were Sutcliffe’s voyeuristic tendencies. He developed an obsession with prostitutes and would travel to Leeds to watch them work the streets of its red-light district.

1970s Jack the Ripper? A serial killer emerges in Yorkshire

The earliest known instance of Sutcliffe attacking someone occurred in 1969, when he struck a young woman on the head with a sock stuffed with a stone. Just six years later, he’d escalated, trading the sock for much more dangerous weapons: hammers and knives.

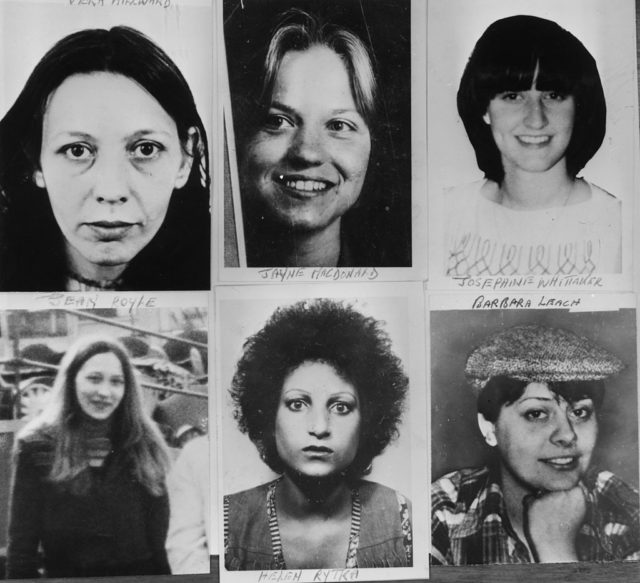

From 1975-80, Sutcliffe killed 13 women and attacked another seven more. His murder spree began in October 1975, when he attacked Wilma McCann, a prostitute and mother of four. He stabbed her 15 times in the neck and stomach after hitting her in the head with a hammer.

He later explained how this killing spurred him to commit more, saying, “After that first time, I developed and played up a hatred of prostitutes in order to justify within myself why I had attacked and killed Wilma McCann.”

The murders that followed that of McCann’s were largely against other sex workers. However, there were some women attacked and killed who were not involved in the sex trade. The murders primarily occurred in Leeds, with others noted in Huddersfield, Bradford, Silsden, Manchester, Halifax and Keighley.

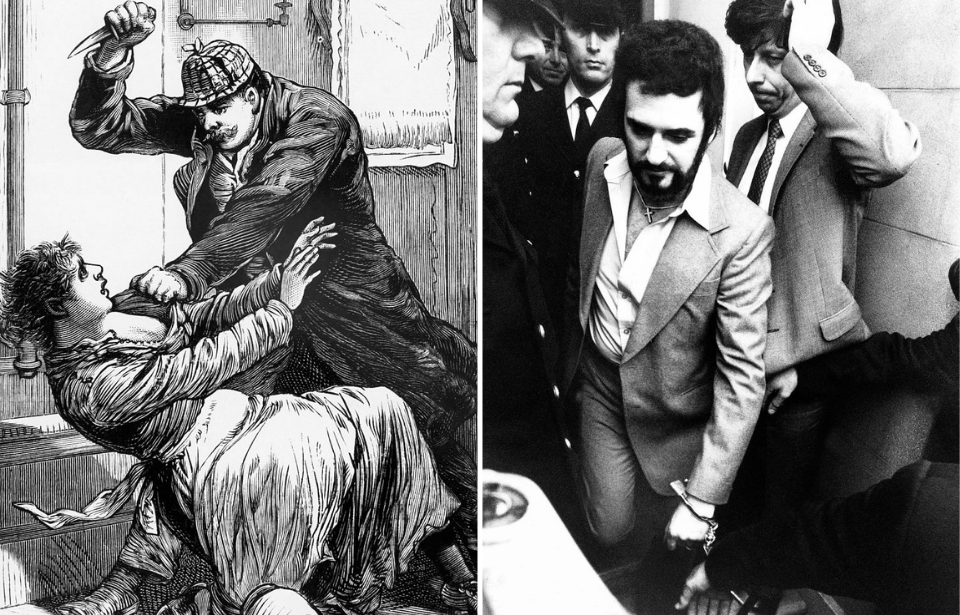

Sutcliffe’s method of murder remained consistent throughout the killings. He incapacitated his victims by hitting them on the head with a hammer, after which he repeatedly stabbed them in the neck, chest and lower abdomen. There are also reports he sexually assaulted them. This prompted the media to dub him the “Yorkshire Ripper,” due to the similarities between his killings and those committed by Jack the Ripper nearly a century before.

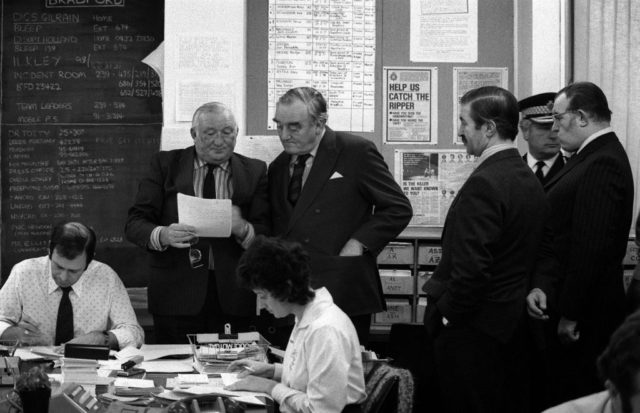

A botched police investigation

The police investigation into the Yorkshire Ripper killings was one of the largest and most expensive in British history. Approximately 2.5 million man-hours were spent on the case.

The piece of evidence that placed Sutcliffe on investigators’ radar came from the handbag of victim Jean Jordan. Within a secret compartment was a £5.00 note, believed to be from her killer. It was traced back to a specific bank, and police were able to narrow down its possible owners to some 8,000 individuals. Five thousand were interviewed, including Sutcliffe, who claimed to have been at a family party at the time of the murder. This was corroborated by his wife.

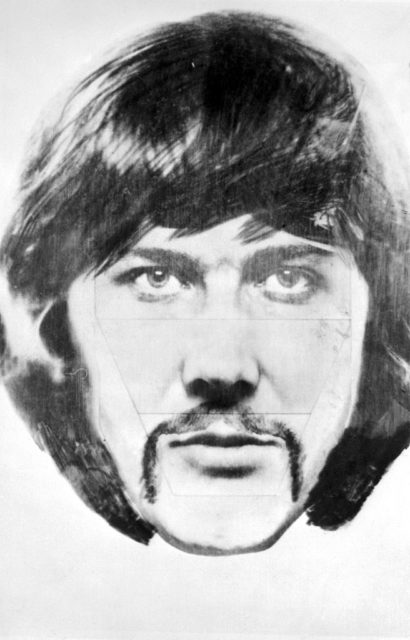

Sutcliffe would be interviewed nine times over the course of the investigation. One such time was following the attack on Marilyn Moore in 1977. Having survived, she was able to provide a description of her assailant. A boot print had also been left on her leg. Unfortunately, investigators never had enough evidence to hold Sutcliffe, and while they did arrest him for drunk driving in April 1980, he was released on bail. While awaiting trial, he committed two more murders and an additional three attacks.

The investigation has been the subject of criticism. Among the issues discussed include investigators disrespecting those victims who worked in the sex trade; the discounting of information from those deemed to not fit the victim profile; and falling for hoaxes, including fake letters and a phone call from someone claiming to be the Ripper but whose voice didn’t match that of the killer.

There was also an issue with processing information, including a tip from Sutcliffe’s friend. His report was lost among the piles of documents collected over the course of the investigation.

After the trial, the investigation was subject to a review by the Inspector of Constabulary Lawrence Byford. The report was released to the public in 2006 and confirmed the criticism toward investigators was warranted.

Speaking about the investigation, West Yorkshire Police Chief John Robins acknowledged the force dropped the ball: “Failings and mistakes that were made are fully acknowledged and documented. We can say without doubt that the lessons learned from the Peter Sutcliffe enquiry have proved formative in shaping the investigation of serious and complex crime within modern day policing.”

Arrest and trial of the Yorkshire Ripper

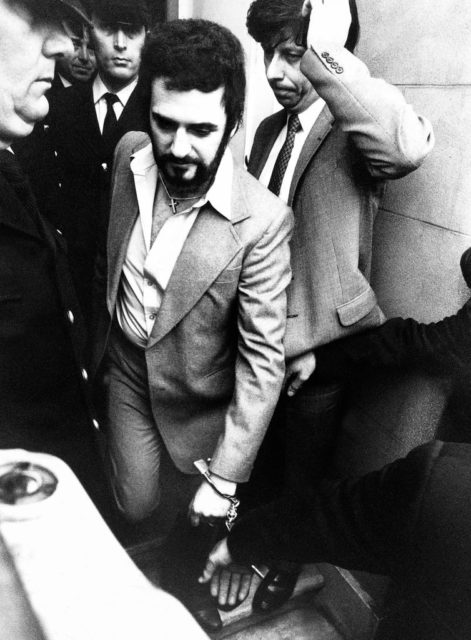

Police nabbed Sutcliffe on January 2, 1981, after two officers noticed his car parked in an area known for prostitution. In the vehicle with him was sex worker Olivia Reivers. When a check was done on the car, the officers discovered its plates were false. They proceeded to arrest Sutcliffe, but not before he asked to relieve himself nearby. It was at this point he ditched a hammer and knife he’d hidden, presumably to attack Reivers.

Following his arrest, the two officers noticed Sutcliffe bore a strong resemblance to the suspect sketch of the Yorkshire Ripper. He was interrogated for two days, after which he finally admitted to being the killer. He spent the next day detailing his crimes.

In May 1981, Sutcliffe stood trial for 13 counts of murder. While he pled not guilty, he did plead guilty to manslaughter, citing “diminished responsibility.” He claimed he’d been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and had heard voices telling him it was “God’s will” that he kill prostitutes. In actuality, he wasn’t diagnosed until after he was convicted and imprisoned.

The plea was unsuccessful and Sutcliffe was found guilty on all 13 counts of murder, as well as seven counts of attempted murder. The judge sentenced him to 20 life sentences, to be served concurrently.

Rationale for the Yorkshire Ripper killings

As aforementioned, Sutcliffe claimed divine voices in his head had told him to kill prostitutes. For many, however, his motive remains unclear.

Some believe the murders were an act of revenge for being swindled by a prostitute. Other analyses found no evidence of him having sought the services of prostitutes prior to the killings, noting only his obsession with watching them.

How similar was Sutcliffe to Jack the Ripper?

Sutcliffe is often referred to as the “1970s Jack the Ripper,” but how similar were his murders to his namesake?

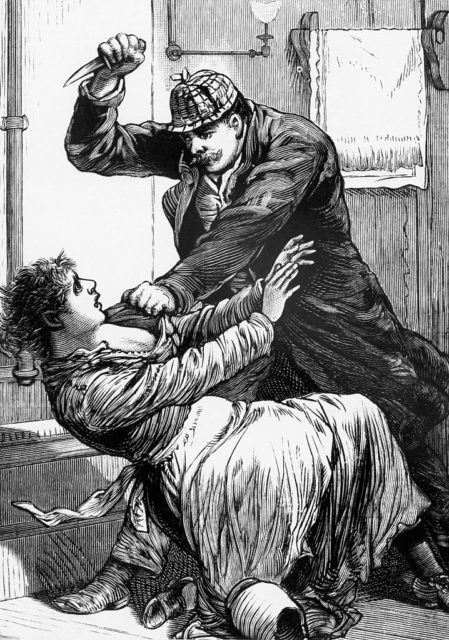

Let’s start with the similarities. Both fully embodied the “ripper” moniker, which is typically given to murderers who mutilate the bodies of their victims, who almost always are women. This lends itself to the victim profile. Prostitutes were the targets of both Sutcliffe and Jack the Ripper, although the former did sometimes deviate.

A major similarity between the two is their method of killing. Jack the Ripper stabbed his victims and removed their organs with surgical precision, leading some to theorize he may have been in the medical profession. While Sutcliffe wasn’t as skilled, he did direct his mutilation to the lower abdominal area and sometimes removed his victims’ sex organs.

A final similarity is not as obvious, but is nonetheless important to discuss. While the sprees occurred in different areas of the UK – Jack the Ripper’s in London and Sutcliffe’s in the north – both targeted poverty-ridden areas with bustling red-light districts.

The differences between Jack the Ripper and Sutcliffe are minute compared to the similarities. The most obvious are the time periods in which the crimes were committed (1888 versus 1975-80) and the length of their sprees (11 months versus five years).

Others aren’t as apparent, including the number of victims. It’s agreed Jack the Ripper committed five murders – the “canonical five” – but there is a possibility he could have committed others in the Whitechapel area. Sutcliffe, on the other hand, is confirmed to have killed 13 women, over double that of Jack the Ripper, and attacked seven more.

Finally, there are the letters sent to police during the Yorkshire Ripper investigation. All of them were deemed to be hoaxes, along with the phone call from the person claiming to be the killer. While the majority of the letters allegedly sent by Jack the Ripper were also determined to be fake, there are three which many believe were actually written by him.

Incarceration

Following his imprisonment, Sutcliffe adopted his mother’s maiden name of Coonan. After his schizophrenia diagnosis, he was sent to Broadmoor Hospital, a high-security psychiatric hospital. During his stint at the facility, he was attacked by other inmates, one of whom left him blind in his left eye.

More from us: Murder and Arson: The Dark and Deadly History of Chippendales

Sutcliffe was eventually deemed fit to leave Broadmoor and transferred to HMP Frankland in County Durham. A few years later, in November 2020, he passed away from complications caused by COVID-19. According to reports, he’d suffered numerous underlying health conditions, including heart issues and type-2 diabetes, prior to contracting the virus.