Archaeologists have discovered previously unknown storage rooms in a 4,400-year-old pyramid located in Abusir, Egypt. While their discovery marks an important shift in understanding pyramid construction at Abusir, more interestingly, the find confirms a theory about their existence that is nearly two centuries old.

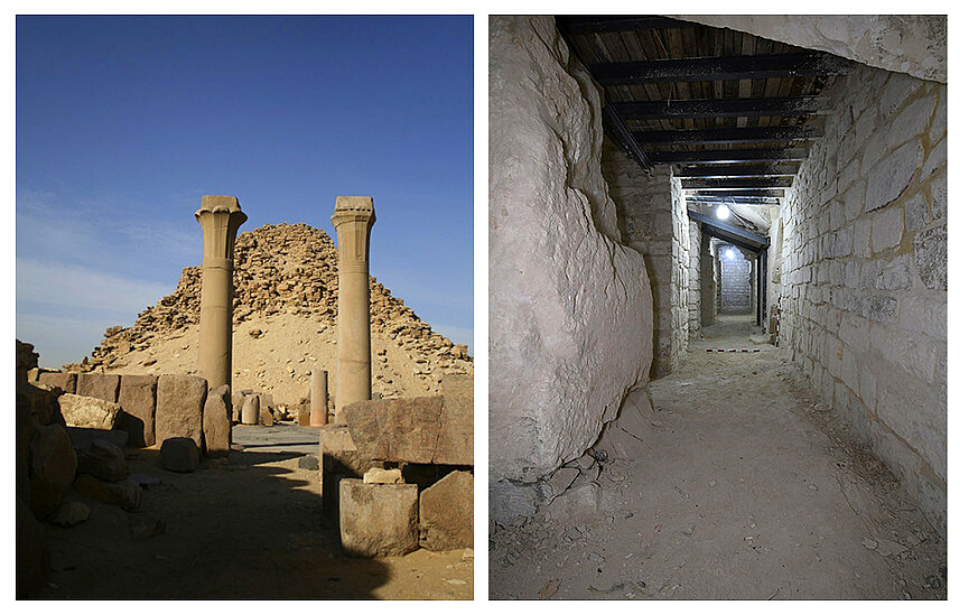

The Sahura pyramid

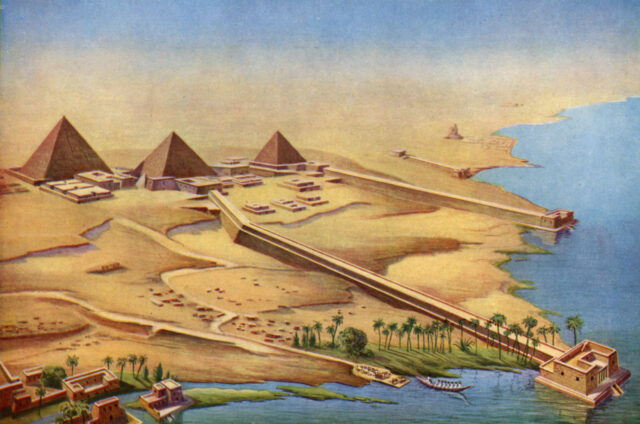

Sahura was the second ruler of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty, ruling for about 13 years in the early 25th century BC. Setting himself apart from previous pharaohs, Sahura had his pyramid built not in Gaza or Saqqara, but in Abusir. This sparked a new trend among his successors, turning Abusir into a main necropolis for three other pharaohs of the Fifth Dynasty during the Old Kingdom period.

By this time, pyramids were falling out of fashion, and so not only was the size of Sahura’s pyramid significantly smaller than those in Gaza and Saqqara, but the construction of the structure was of poorer quality. In fact, it was only the outside of the pyramid that was built of high-quality limestone – the interior was made from poor-quality materials that caused it to deteriorate at a significantly faster rate.

The British archaeologist was right

The very first archaeological endeavors conducted at Sahura’s pyramid took place in 1836 by British archaeologist John Perring. The structure was largely reduced to rubble by this time, but he was still able to note low passageways covered in debris. He hypothesized that these passageways could lead to additional rooms, but most of his peers disagreed, and so they went unexplored for decades.

The first restorations on the pyramid began in 1994, but it is the most recent project, which began in 2019 by a team of Egyptian and German archaeologists, that determined that Perring’s hypothesis was correct. They discovered eight storage rooms that were previously unknown.

Scanning the rooms

The team used 3D laser scanning to survey the interior of the pyramid, providing them with the original floor plan of the structure despite its deteriorated state. From this, they were able to determine where the original retaining walls were located, helping them identify the locations of the eight newly discovered rooms.

In a press release from the archaeological team, they wrote how “This advanced technology enabled comprehensive mapping of both the extensive external areas and the narrow corridors and chambers inside.” For them, “The frequent scans provide real-time updates of progress and create a permanent record of exploration efforts.”

“The discovery of the magazine area inside the pyramid of Sahura has completely changed our understanding of the architecture of pyramids in the Old Kingdom,” Egyptologist and head of the restoration project Mohamed Ismail Khaled wrote. “Sahura might have been the pioneer of this architectural innovation which was adopted by his successors.”

Moving forward, the team intends to restore the storage rooms, a process they expect to “revolutionize a view of historical development of pyramid structures and challenge existing paradigms in the field.” At the same time, they will also work to stabilize what is left standing of the pyramid in the hopes of preventing further collapse.