Aerial photography is the taking of photographs of the ground from an elevated/birds eye position. Usually, the camera is not supported by a ground-based structure. The term aerial archaeology is used to describe the various processes related to the discovery and recording of archaeological sites from the air.

In general, aerial photography is mainly used for visualisation and illustration purposes. This kind of photography is one of the best ways of understanding archaeological landscapes because it reveals and makes sense of features which are too faint, too large or too discontinuous to be appreciated at ground level. A surveying technique that involves taking a photographic record from satellites, helicopters, kites, parachutes, aircrafts and balloons, to aid with the detection of buried archaeological remains and features. We used to see in the TV program – The Time Team.

Aerial photography has been used for many years to identify and record archaeological sites; beginning with balloon flights in the early 1900’s and expanding using open-seated biplanes in the 1920’s and 30’s.

Aerial photographs can be distinguished as either vertical or oblique views. The difference between vertical and oblique aerial photographs lies in the techniques by which they are acquired.

Vertical photographs are often taken from great heights directly above an area (1000 feet). The aim of such reconnaissance is generally to record aspects of the contemporary landscape, but these photographs often incidentally record evidence of past activity. The main limits of vertical photography are its extremely high cost and the fact that in almost all cases the archaeological evidence appears by chance since flights are only rarely undertaken, especially for archaeological purposes. The aeroplane acquires the images by making a series of flights during which the photographs are taken automatically at regular intervals so that each photograph partially overlaps the previous one and the subsequent one. The overlaps provide a three-dimensional view of the territory being photographed, thereby avoiding gaps in the documentation.

Photographs taken at an angle are called oblique photographs. If they are taken from a low angle earth surface–aircraft, they are called low oblique and photographs taken from a high angle are called high or steep oblique. They are considered much more suitable for archaeological applications than vertical photographs, because they are special views selected during the flight by the archaeologist and because they can be acquired under the best conditions in terms of visibility, light and readability of the surface.

Used in combination, vertical and oblique images increase the amount of quality of the information, exploiting on the one hand, their ability to provide an overview and on the other their potential for identifying previously unreported archaeological sites and expanding the knowledge of elements that have only been partially described.

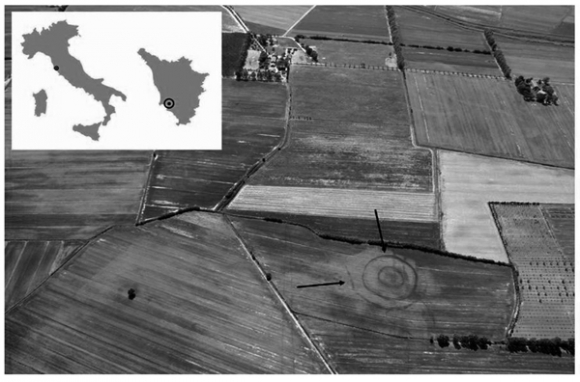

Many of the archaeological sites mapped by aerial archaeologists have been levelled by ploughing and are identified from the photos as crop marks or soil marks. Archaeological sites which have not been ploughed down generally survive as low earthworks or slight stony banks. From the air, these are best viewed in low light conditions, especially in the early morning or evening.

Crop marks are simply patterns in vegetation reflecting differences in the rate of germination, growth and ripening of a crop. These differences are caused by variations in the moisture and nutrient content of the soil. These variations in turn are caused by differences in the structure and profile of the subsoil and can be due to the presence of buried features.

Soil marks are differences in soil colour as a result of archaeological features. During ploughing time, in the months between autumn and spring, differences may be seen in the colour of freshly ploughed bare soils as lighter sub-soils are brought to the surface. With soil marks, the aerial archaeologist is looking directly at the archaeological deposits brought to the surface by the plough where they show as colour differences against the non-archaeological plough soil.

Earthwork sites are those where standing archaeological remains in the form of ditches, earth banks or low walls survive. Even the most substantial of earthworks can appear almost invisible in flat light so they are best photographed when the sun is low in the sky. The ideal time to photograph earthworks is in the early morning, the late evening or in winter, when the low angle of sun-light picks out the slightest of archaeological earthworks as highlights and shadow marks. Earthworks may also be accentuated by floodwater or by differential melting after a light fall of snow.