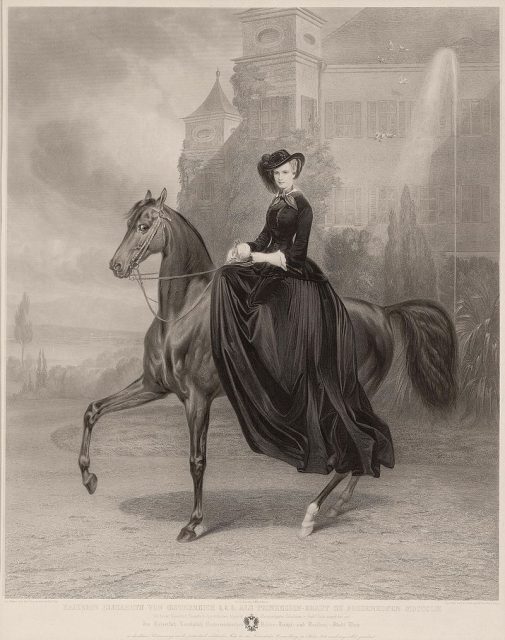

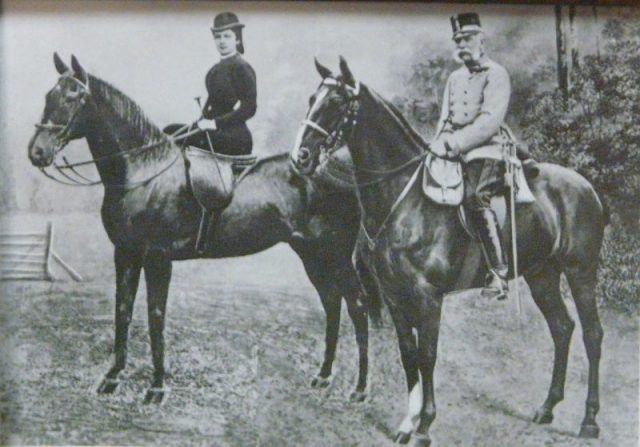

Empress Elisabeth of Austria was born at least a century too soon, really. Had she been alive today, she surely would have ruled Instagram, not to mention the red carpet. Sissi, as she was affectionately known, was one of the great beauties of 19th century Europe, her silk gowns and elaborate coifs copied throughout the continent. (Put another way: She was Diana before there was a Diana.)

Born Elisabeth Amalie Eugenie, she became royalty after wedding and bedding Emperor Franz Joseph in 1854, at the age of 16, and immediately made her mark as the trendsetter of her time. But even by today’s standards of self-absorption, Sissi’s beauty regimen was shockingly excessive.

The Empress Elisabeth’s trademark was her thick chestnut-colored hair, which flowed down to the floor. Naturally, the care of these strands was no simple wash-and-dry affair. It was, in fact, a high-maintenance ritual that consumed (at least) several hours a day. Each morning, Sissi’s hairdresser, Fanny Feifalik, would be summoned to work her considerable talents—brushing, braiding, and twisting her mistress’s strands into elaborate ‘dos that would become the talk of Europe.

Fanny quickly became invaluable and cunningly used her position to her advantage. If, for example, she felt the least bit slighted, in would walk another hairdresser in her place, much to the dismay of the empress, who reportedly bemoaned, “After several such days of hairdressing, I am quite worn down. She knows that and waits for capitulation. I am a slave to my hair.” Eventually, Fanny was granted the lofty-sounding title of Imperial Hairdresser, along with a salary of 2,000 “guldens” a year, a tidy sum back in the day.

To be fair, Fanny earned every single coin. Tending to Sissi’s tresses was no small task. To wit: After each session, Fanny was to bring forth a silver bowl holding hair that had come out during the combing or styling. This could have been a dicey affair, but Fanny was shrewd. To prevent a potential tongue-lashing from her mistress, she employed a bit of trickery, hiding stray strands on a piece of adhesive tape, which she kept concealed underneath her apron.

According to Ludwig Merkle’s biography, Sissi’s hair was washed every three weeks with a mixture of raw eggs and brandy. Afterwards, she would slip into a waterproof dressing gown and pace the floor until her hair dried.

At times, the massive weight of that considerable mane led to headaches so severe, they kept Sissi cloistered away in her room. Ribbons were used to lift her hair up and lessen the poundage bearing down on her pretty little head.

Just as complicated: Sissi’s skincare routine. To ward off wrinkles, she created a facial masque composed of crushed strawberries and applied another masque—this one made of raw veal—before retiring to her bedchamber. Sissi’s skin wasn’t the only thing she obsessed over. To maintain her slender figure, she ate very little—perhaps just a thin gravy for dinner. Other times, she would subsist on little more than eggs, oranges, and raw milk.

Her fitness routine was no less Spartan. Sissi endured hours of exercise, working out with rings, lifting weights, and taking brisk walks lasting several hours. Apparently, the drastic measures worked. As biographer Brigitte Hamann noted: “To the nineteenth century, which stamped even 30-year-old women as matrons, especially when they had borne several children, Empress Elisabeth was an extraordinary phenomenon.”

The ruthless dieting and exercise helped Sissi squeeze herself into one of the most fashionable items of 19th-century clothing—the corset—which whittled her already tiny waist to a jaw-dropping 19.5 inches. It was this bit of conceit that almost helped Sissi cheat death just a little.

On September 10, 1898, the then 60-year-old empress was on her way to a steamer ship in Geneva, Switzerland, when she was stabbed by an Italian anarchist. Sissi crumpled to the ground, but managed to get to her feet and make it to the landing bridge of the ship, before losing consciousness. The Empress was taken to a nearby hotel, where she died. It was then that her companions learned the full extent of her injuries.

Related story from us: The bizarre practice of foot-binding was once a symbol of beauty in China

The thin metal file that she had been attacked with penetrated her heart and lungs. That she could summon enough strength to walk to the ship was nothing short of astonishing. Determined to maintain her girlish figure, by donning a corset, just may have prevented Sissi from bleeding to death at the scene.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.