It could be the opening scene of a cheesy horror B-movie: In a storage room of a museum in Hungary, the century-and-a-half-old remains of a baby were found in a forgotten dusty corner.

The baby, who had been dug up from a medieval cemetery, had a hand, just one, that was bizarrely mummified and had turned the color green.

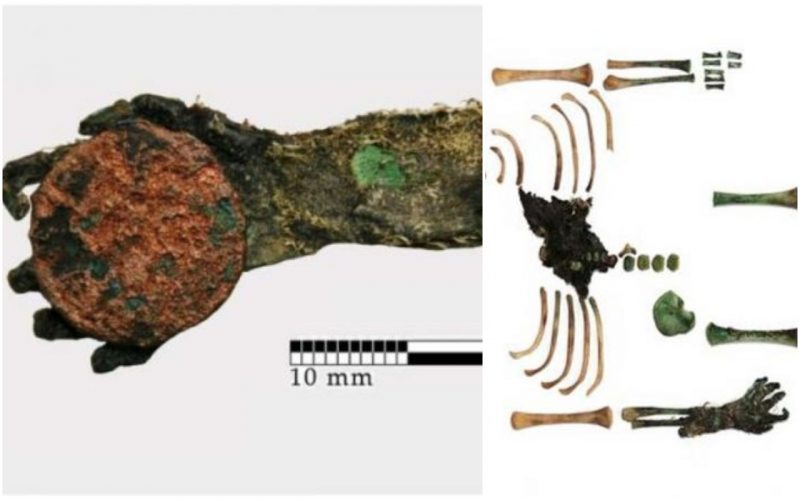

The discovery was a genuine scientific riddle. Archaeologists who carried out a study to resolve the case say the mummification of just one small hand happened because the baby was clutching a copper coin.

All that remained of the rest of the body was the skeleton, apart from another small patch of desiccated flesh on the child’s back.

Scientists have long been familiar with copper’s anti-microbial properties, as well as the tendency for copper or bronze jewelry placed as grave goods to cause the bones of ancient bodies to discolor.

But so far as János Balázs and his team are aware, there is no previously recorded case of mummification caused by the metal.

Dr. Balázs, a biological anthropologist from the Hungarian-based University of Szeged, and his colleague Zoltán Bölkei opened up the box filled with tiny bones in 2005.

It was stored in the museum archive and had come from an archaeological dig at a site near the village of Nyárlőrinc, Hungary, that had been carried out some years earlier.

Over 500 graves, most of them dated to the 12th until the 16th centuries had been excavated in the dig, and the scientists were working through the slow process of examining the finds.

Disturbing occasions when ancient Egyptian curses seemed to come true

It took over a decade for the experts to unveil answers about the unusual mummified hand. Their results were finally published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences in April 2018.

Science reporter Nicholas St. Fleur, writing in the New York Times, reports that the team members were puzzled by the strange distribution of discoloration on the skeleton.

They guessed the green color was caused by copper, and chemical analysis indeed showed the baby’s remains to contain hundreds of times more copper than normal.

But where was the object that must have been in contact with the tiny body? And why were some parts of the bones so distinctly green, and others not? As the investigation progressed, just like a mystery novel plot, learning answers opened up more questions.

The team concluded that the child would have weighed no more than two pounds, and was likely stillborn or so premature that it died soon after birth.

Dr. Balázs explained to the New York Times how an important piece of the puzzle was found in another local museum that was also holding some of the artifacts from the dig.

When the team searched through these other boxes, they found a broken ceramic pot together with a copper coin that perfectly matched the shape of the mummified hand.

This was the vessel in which the baby had been buried, and here too was the source of the copper in the child’s bones.

The placing of a copper coin in its hand follows a common theme of many ancient cultures, to allow the deceased to pay the fee so their soul doesn’t get stuck in purgatory.

Smithsonian magazine writes that the Nyárlőrinc baby is similar to other cases where babies have been buried in a pot with a coin to pay St. John the Baptist for their baptism.

This practice hadn’t been confirmed in Hungary; however, it did explain the pattern of green patches on baby’s forearms, hip bone, leg bones, and a few vertebrae, as it must have been in a crouched position to fit into the pot.

When the research team examined the coin, the mystery deepened even further. According to the New York Times, the “kreutzer” coin would have been in circulation from 1858 until 1862, much later than the other graves in the cemetery.

It is also a Christian tradition that was thought to have died out by the mid-19th century.

Bereczki’s team think that whoever gifted the child with a coin was perhaps desperate for a way to ensure it would reach the afterlife.

“They kind of succeeded at saving not necessarily the soul, but some kind of legacy of this little kid,” he told the Times.

Two more similar burials of premature babies have been found at the site, too. However, only one of them was found to have green bones and was linked to another coin and pot.

According to the Smithsonian, mummification of human remains believed to have been due to copper has been stumbled upon at other archaeological sites in the past, for example, a discovery in Siberia in 2002 of 34 copper-wrapped mummies.

However, archaeological investigation was halted due to protests by the local population. This is possibly the first scientific paper to officially attest to copper mummification.

The remains of the tragically lost infant are currently exhibited at the Móra Ferenc Museum in the city of Szeged, the third largest city in Hungary.