William Shakespeare will always be remembered as a pivotal figure in the history of literature, as well as in the history of Western Civilization.

He has provided us with such depth and insight into the existential horror of life, the tragedy of love and passion, and the fundamental questions regarding morality and ethics―all of which are embedded and intertwined with our perception of these subjects today, more than 400 years after the author lived. His name is usually associated with meaningful tragedies, complex characters such as Hamlet, Cordelia, King Lear, and Shylock, and heartbreaking love stories such as Romeo and Juliet. But could the Immortal Bard crack a joke now and then?

Well, judging by his comedic opus, which includes the timeless classics such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night, our favorite author of the Elizabethan era was sure able to make people laugh.

But Shakespeare’s extraordinary writing craftsmanship and subtle wordplay provide us with more than just a testimony of his humor and wit.

As much as he loved to produce plays that brought the audience from laughter to tears in a matter of minutes, the English master of drama was very pedantic when it came to titles, using the rhetorical effects of similar-sounding words and terms with multiple meanings to plant subversive allusions.

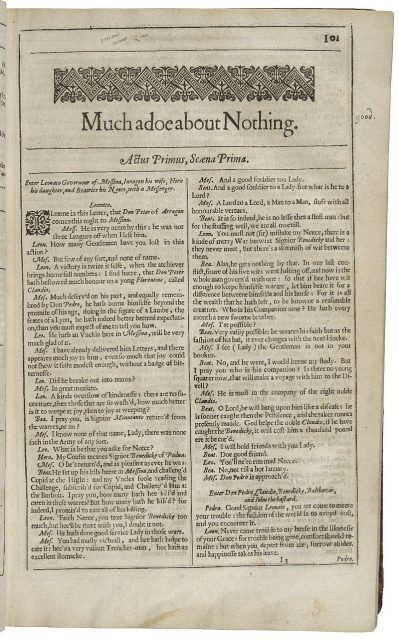

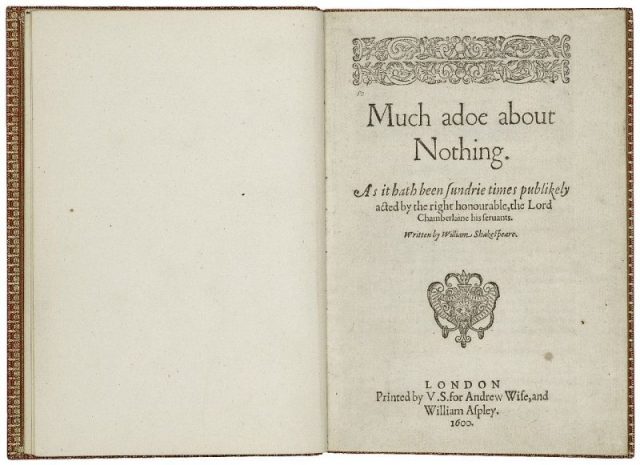

It was in this figurative field of battle that he could practice his beloved ability to maketh a pun. And when it comes to puns, one title stands out among other, for it offers an entire myriad of meanings, all of which perfectly illustrate both its plot and its characters: Much Ado About Nothing.

What strikes one as a generic title intended for a light-hearted piece unravels as a witty, clever, and provocative sentence, with its true meaning largely forgotten in the labyrinth of a language which has evolved so much since the 1600s.

But if we trace the implications of this title back to Shakespeare’s contemporaries, we would realize that the word “nothing” back then was pronounced similarly to the word “noting.”

Related Video:

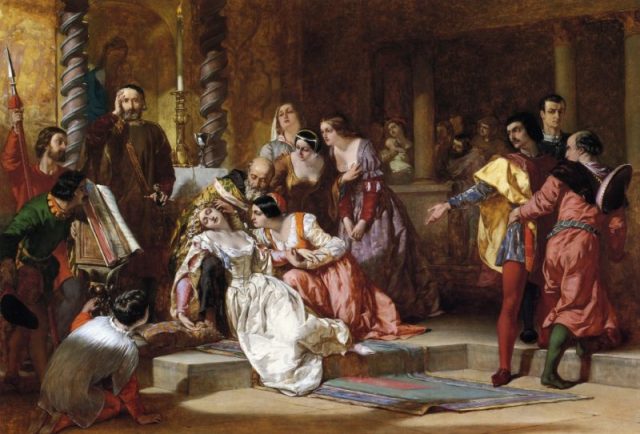

Now, since Much Ado About Nothing is a comedy of errors, implying that much of the plot is based on a misunderstanding, false claims, and gossip, the “noting” part refers to meanings such as taking notes and badly interpreting them, falsely concluding a situation and even spying or eavesdropping.

With this part cleared up, the first layer of potential interpretations of the title, we proceed further into the world of 16th-century English slang.

For a common person living in Queen Elizabeth’s or King James’ England, “something” and “nothing” had a rather specific meaning, one not used in a well-mannered conversation between the ladies and gentlemen of the time.

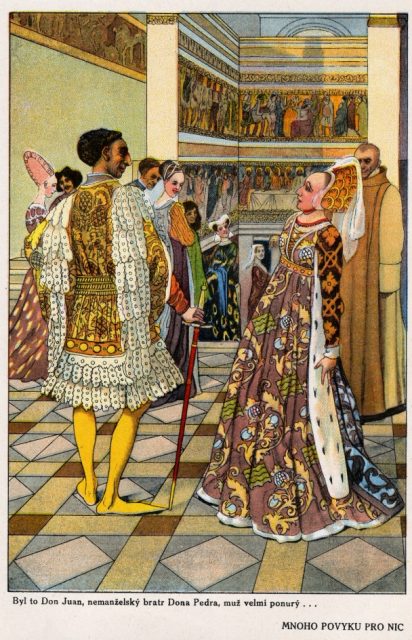

The word “something” referred to a penis, while the word “nothing” was a substitute for vagina. Setting the tone to flirtatious and frivolous, Shakespeare managed to invoke the deeply erotic side of this story set in Messina, Sicily, which was then part of the expanding Kingdom of Aragon.

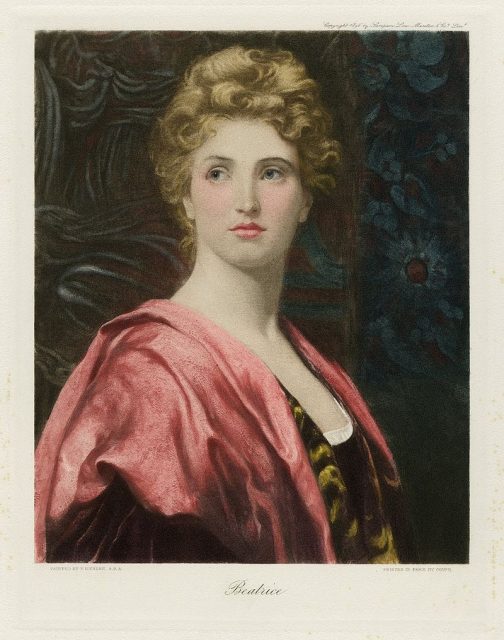

Since Much Ado About Nothing revolves around male characters―Benedick and Claudio―and their female counterparts―Beatrice and Hero―going through a series of unnecessary mishaps only to end up together joined in marriage, the title completely encompasses the plot which thrives on gender roles of the late Renaissance period.

Conventions take hold of the male characters, who see themselves as morally superior, while clichés of women being prone to adultery are strongly ridiculed, as all such slurs prove to be false.

This interesting take on reversing gender stereotypes becomes even more clear in a poem recited by one of the characters, titled “Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more.”

With its opening verses, the song proclaims men as being the ones prone to adultery and deceitfulness, rather than women:

“Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more.

Men were deceivers ever,

One foot in sea, and one on shore,

To one thing constant never.”

Even though one might think that this play sparked outrage during the time it was initially staged, Much Ado About Nothing was exceptionally well accepted by the audiences.

CC BY-SA 4.0

The surprising popularity of this theater piece confirmed that a complex society, well-aware of its rules and norms, is also aware of the occasional need to subvert them, in order for them to remain in power.

Not that Shakespeare minded―after all, such space gave him the opportunity to mock, ridicule, and question authorities and social conventions throughout his career, appearing as a court jester allowed to say whatever he wants, for his words lack the power to change anything.

Related Article: Did a Man Named William Shakespeare Actually Exist?

Despite such appearance, his words did change a lot.

But let us now address the elephant in the room. Was the spelling of the name “Benedick,” instead of “Benedict,” also part of Shakespeare’s wordplay repertoire, or was there no pun intended? Hmmmmm.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. His areas of interest include history, particularly military history, literature and film.