During the Great Depression, which lasted from 1929 to 1939, the U.S. government sent a multitude of photographers out around the country to document the pains and trials that many Americans were suffering during this time.

It was meant to be a way to help show American life during the Depression, especially the struggles of rural life.

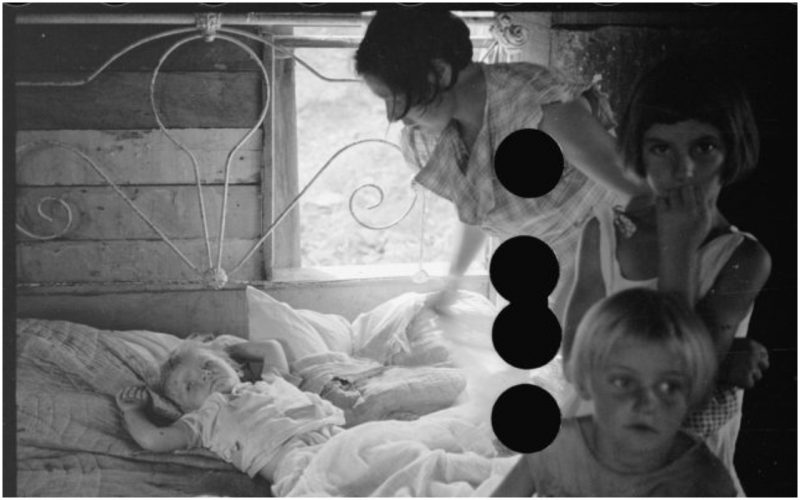

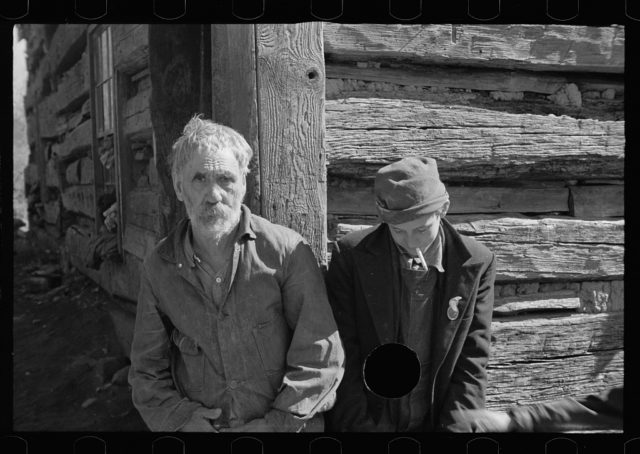

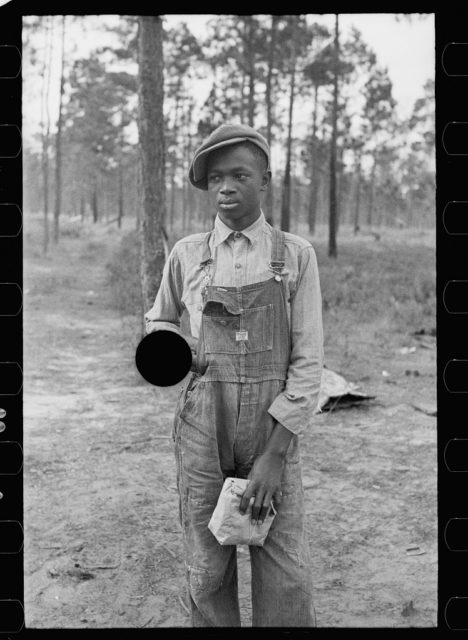

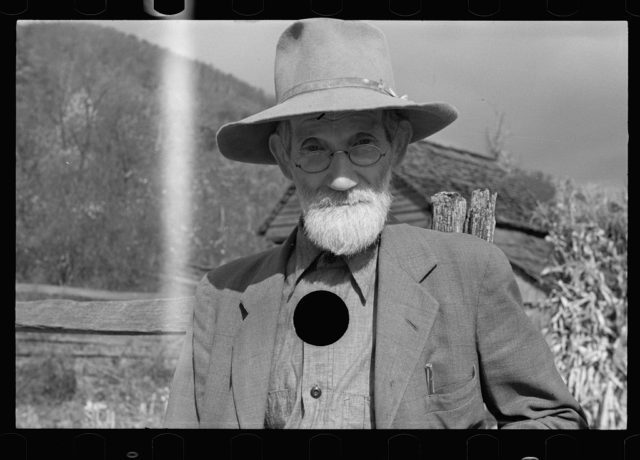

The photographers captured families living in shacks, children dressed in rags, workers in factories, and the farmers who spent hours outdoors trying to save their crops.

They would also document the eerie landscapes that featured abandoned homes falling apart. But it wasn’t all just somber photos. Photographers would also document friends playing, siblings laughing together, and sometimes even pets.

Before heading out to capture images, the photographers were briefed over what the photography board wanted to see.

The board, headed by Roy Stryker, a photographer and economist who worked for the Farm Security Administration, was very specific in their requests and had extremely high standards.

So high, in fact, that if Stryker reviewed a negative that he found to be of poor quality, he would punch a hole into it which would prevent the image from ever being used again.

The small yet obvious hole in the photo would be placed in various areas. One might block out the face of a person while another would be placed up in a corner looking like a dark sun over a vast field.

Some of the best slang from the 1930s era.

The checklist Stryker used to determine whether the image was used or not isn’t really known. However, sometimes if the image wasn’t focused or taken with a tripod, it could mean an instant hole punch.

Other times, if the negative showed success in certain areas that could make a specific group of people look bad at the time, it would also be ruined by him.

For instance, many photographs of African-Americans were excluded by Stryker, especially if it showed them to looking affluent, something which went against the socioeconomic ideas of the time.

This process was extremely controversial. Photographers who spent hours traveling around trying to find the perfect shot were dismayed when their negatives were ruined by Stryker’s hole puncher.

He would constantly criticize photographers for not focusing on the subject well or for taking too many photos of the same subject. As former photographer Ben Shahn once said, “Roy was a little bit dictatorial in his editing and he ruined quite a number of my pictures, which he stopped doing later. He used to punch a hole through a negative. Some of them were incredibly valuable.”

Another photographer, Edwin Rosskam, stated, “The punching of holes through negatives was barbaric to me. I’m sure that some very significant pictures have in that way been killed off, because there is no way of telling, no way, what photograph would come alive when.”

The association was filled with many talented photographers, most of whom are well-known today. Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Theodor Jung, and Arthur Rothstein, to name a few, ventured across the South to document life during these years. Stryker continued his hole punching trademark for years, until 1939 which he finally listened to the pleas of the photographers to stop ruining their work.

The pictures you see here are just a handful of the images that Stryker deemed to be of bad quality.

While thousands of images might not have been used by Stryker, many of the ruined negatives were saved and digitized into the Library of Congress’ system. Many are also on view at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Read another story from us: Horseback librarians during the Great Depression

The images are an interesting window into the past and tell the intricate story of the lives of those who lived during this time, making them a true historic treasure.

Rachel Kester is a freelance writer who has written for sites like 30A and Mystery Tribune and lives in the great state of Virginia.