Forgeries are nothing new to the art world. For as long as art has had exceptional value in the world, there have been clever con artists who try to hone in and make a buck. Indeed, one of the greatest risks a purveyors of fine art runs is accidentally purchasing a forgery. Nothing could be more embarrassing than to unveil an original Van Gogh, only for your friends to scoff at you for having purchased an obvious fake!

And while forgeries are looked at as a negative thing in 99 percent of all cases, there are some exceptions, such as the Shadwell Dock forgeries. In 1844, a man by the name of William “Billy” Smith made the acquaintance of an antique dealer.

William Edwards took a liking to Smith and his friend Charles “Charley” Eaton, and would frequently purchase items and artifacts of note from them.

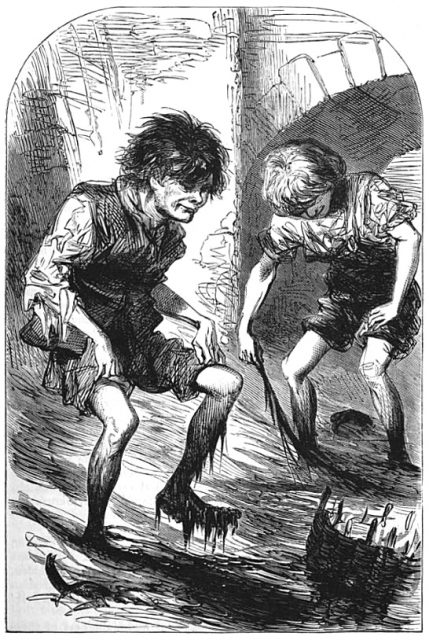

Eaton and Smith were known as mudlarkers, individuals who would sift through mudflats in places such as the River Thames in order to find rare and valuable items. This was a simple way to make a meager living, but Eaton and Smith were after something more than just a small wage for collecting nick knacks. They hatched a cunning plan to increase the value of the items they were selling to the antique dealer, simply by creating forgeries.

They put their heads together to create all manner of forged medieval items, creating coins, medallions and spearheads. By making the items out of pewter and bathing them in acid, Eaton and Smith were able to create aged, worn out looking artifacts that they claimed were recovered from the Shadwell Docks where an excavation was taking place.

There were numerous problems with the forgeries. The two men were not well educated or trained, in fact, they were both illiterate. When replicating medallions, their most popular creation, they didn’t bother to put inscriptions which were commonplace for medieval medallions.

On top of that, they included dates on the coins that used Arabic numerals. These numbers were anachronistic for the time period they supposedly came from, as Arabic numerals were only widely adopted in 16th century England. While their ambitions were high, Eaton and Smith weren’t the best at creating forgeries.

Yet, their buyer, William Edwards, was unaware of the forged nature of the items. He purchased a great many of them from the pair, acquiring over 1,100 items. One of William Edward’s acquaintances, George Eastwood also took an interest in the artifacts and quickly began buying them from Edwards. He would eventually go straight to the source, bringing in even more money for Eaton and Smith.

Things were running smoothly for the pair, until members of the British Archaeological Association began to take notice of a large influx of medieval artifacts pouring in from a single source. After examining these items, Henry Syer Cuming gave a lecture to the BAA, claiming that they were nothing more than poor forgeries at best.

These words would be published in a few magazines, one of which was The Athenaeum. George Eastwood felt personally attacked by these words, after all, he was in the business of selling such artifacts. Even though he wasn’t named in the articles written, he still believed himself to be the subject of libel and took The Athenaeum to court.

The court case would ultimately help Eastwood’s reputation, as he fought hard to prove the authenticity of what he had been purchasing. One ironic testimony in his defense was by Charles Roach Smith.

Charles Roach Smith, co-founder of the British Archaeological Society, made the case that they were so poorly designed that the items couldn’t possibly be a forgery. If they had been forged, the con artists would have done a much better job. In his eyes, the crudeness of the creations meant the items were indeed authentic.

6 of the Biggest Treasure Troves Ever Discovered

The court case concluded without a conviction. Since Eastwood’s name had never been mentioned in the article published by The Athenaeum, it was ruled that they didn’t commit libel. However, the court did state that they had faith in Eastwood and the business he conducted. This would boost the popularity and value of the artifacts for a time.

Eventually the truth would come out. A businessman and antiquarian by the name of Charles Reed began his own investigation into the truth behind the artifacts. The standard line that Eaton and Smith gave about acquiring their stock was that they had bribed the workers at the Shadwell Docks in order to gain access to the premise.

After poking around, interviewing the workers and trying to find suppliers, Reed concluded that there was no evidence that Shadwell Docks had ever produced any such artifacts. He did come across a scavenger who claimed the pair were creating forgeries. Reed paid this man to steal the plaster of Paris molds that were used to create these artifacts.

In March 1861, Reed revealed his findings to the world, definitely proving that Eaton and Smith’s work were fakes. The pair would continue to produce forgeries but would not reach the levels of success they once had achieved again.

In the modern world, however, these forgeries — known as Billy and Charleys — have become relatively valuable. Viewed primarily as folk art, since they were created by men who weren’t educated or even literate, Shadwell forgeries are often sought after in the art world.

Read another story from us: This “Chapel of the Macabre” is Decorated with Thousands of Human Bones

Museums have collections of these artifacts and some of them sell for even more than the original artifacts Eaton and Smith were trying to replicate. And of course, as with any art that sells well, there have been reports of forgeries of Eaton and Smith’s work circulating the art world. It just goes to show that if something is successful in the art world, you can bet on someone copying it, even if they’re copying a copy.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.