In the 507 years that Ming the Clam was alive at the bottom of the Norwegian Sea, the world changed. Great empires rose and fell again into the dust, the Industrial Revolution transformed human society, and two world wars claimed millions of lives.

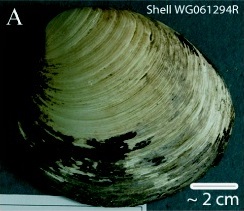

Ming’s age was calculated by counting the annual growth rings on his shell. However, the clam’s long life came to an abrupt end at the hands of the very scientists that were attempting to discover his age.

In 2006, a team of British scientists were engaged in a fact-finding mission off the coast of Iceland, as part of a study to discover the effects of climate change. Ming was collected with other specimens after they dredged the seabed.

According to the Sunday Times, the scientists pried open the clam, killing it in the process. It was only later that they discovered that Ming was 507 years old, potentially one of the oldest living animals on Earth.

Ming the Clam was born in 1499, which makes him the oldest living animal ever discovered. In the year that he was born, Leonardo Da Vinci was painting the Mona Lisa, and the Tudor king Henry VII was sitting on the throne of England.

The clam was nicknamed Ming in the British media, as he was born during the rule of the Chinese Ming dynasty.

In Iceland, he was named Hafrun, a female Icelandic name roughly translated as ‘mystery of the ocean’. The actual sex of the clam, however, remains unknown. He (or she) had been alive for so long it was impossible to determine.

Ming’s untimely death may not have been entirely in vain. The scientists who discovered him hoped to analyze the growth rings on his shell in order to uncover the secrets of long life, in addition to understanding the long-term effects of climate change near the Arctic.

Scientists funded by Help the Aged are attempting to find clues in Ming’s rings that will help us to understand why some creatures are able to resist the negative effects of aging. This could pave the way for discoveries that will help people to live for longer.

The data from Ming’s shell has also helped scientists to understand the impact of climate change on marine life. According to National Geographic, quahog clams provide a particularly useful source of information about marine conditions, as each annual ring growth stores information about the environment and atmosphere in which they lived.

By examining each ring, scientists are able to reconstruct historical sea temperatures and climatic conditions. Analysis of Ming, and the other clams in the sample, has demonstrated that changes to the world’s atmosphere since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution are driving changes in sea temperatures and currents. These important discoveries help us to better understand the effects of human-induced climate change.

Ming the Clam is the oldest (non colonial) animal ever discovered, whose age can be calculated precisely. However, it’s highly likely that there are many more similar specimens under the sea, which may even be significantly older.

The sample taken by the British scientists in Iceland was extremely small, comprising only 200 clams. Although Ming was the oldest clam found in the sample, it’s actually very likely that there are many more clams off the coast of Iceland, which may be 400 years old or even older.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1fMTsxEKgIs

According to National Geographic, quahog clams like Ming stop growing when they reach a certain age and size. This means that it’s actually very difficult to tell whether a clam is 80 years old, or 300 years old.

Read another story from us: Extinct Predator Cave Lions Could be Brought Back to Life

Although Ming’s life was cut short prematurely, he’s an important reminder that the oceans contain many mysteries yet to be discovered.